OTD in 1968, a B-52 carrying 4 B28 H-bombs on airborne alert over the BMEWS radar at Thule, Greenland, caught fire and crashed onto the ice at ~560mph. The conventional high explosives in all four bombs exploded, scattering 6kg of plutonium; 35,000 gal. of jet fuel burned debris.

Thule Monitor was a special airborne alert mission to confirm that the BMEWS radar—which was (and is) critical to detecting an ICBM/bomber attack over the North Pole—was unscathed if communication lines went down, or destroyed, signaling the (presumptive) start of a nuclear war.

The fire aboard the B-52G was caused by human and mechanical error. A crewmember stuffed four foam rubber cushions beneath a seat on top of a heating vent. When the heat was turned up hours later, a heater malfunction ignited them, filling the cabin with flames and thick smoke.

Six crew members bailed out and survived, although two navigators were injured. A second pilot died trying to bail out.

The next day, the Strategic Air Command removed all nuclear weapons from airborne alert aircraft.

The next day, the Strategic Air Command removed all nuclear weapons from airborne alert aircraft.

Here’s how the New York Times covered this catastrophic accident. Note the short article after the end of the main article about the reaction in Denmark, which at the time governed the ice-covered island: “150 Protest in Copenhagen.”

Interestingly, shortly after this accident, the DOD released a list of 12 previous serious nuclear weapons accidents involving USAF planes. The New York Times published this list (adding three other accidents) below its coverage of the Thule accident on January 23, 1968, page 12.

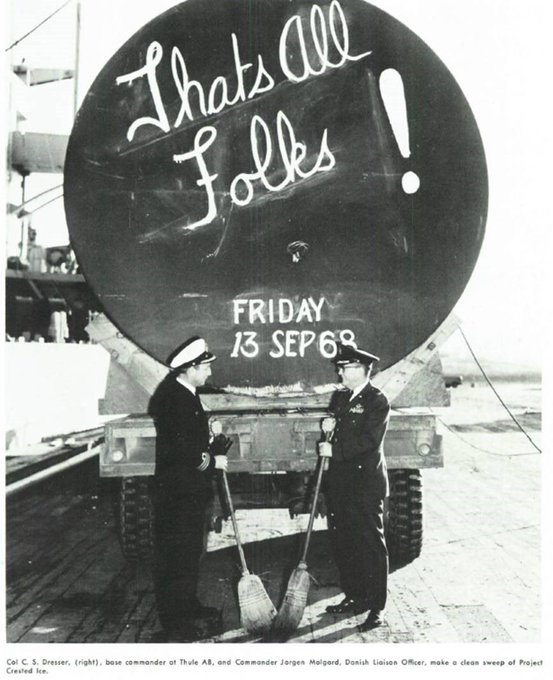

An extensive, nearly 8-month cleanup effort—dubbed “Dr. Freezelove”—collected, packaged and transported 10,500 tons (237,000 cubic feet) of contaminated snow, ice, and debris to the Atomic Energy Commission’s Savannah River Plant in South Carolina for burial in a shallow trench.

In 2015, the BBC broadcast an interview with Jens Zinglersen, a Dane who managed supplies at Thule Air Base, witnessed the catastrophic crash, and was the first person on the scene. (CAVEAT: Despite rumors, there is no missing H-bomb beneath the ice.) bbc.co.uk/programmes/p02…

What was reportedly never recovered was the U-235 “spark plug” from one bomb. That’s only part of the thermonuclear secondary (albeit the most important part). For more, see this comprehensive 2009 report by the Danish Institute for International Studies: pure.diis.dk/ws/files/24287…

Here is the official report on Project Crested Ice, detailing the activities of the Defense Atomic Support Agency Nuclear Emergency Team in Greenland to support recovery and contamination control efforts following the 1968 accident: apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fullte…

And here is volume one of the Strategic Air Command’s declassified 1969 history of Project Crested Ice: nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb2…

And finally, here is a collection of high-quality, declassified photographs and illustrations documenting the accident and the extensive search, recovery, and cleanup effort: osti.gov/opennet/servle…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh