Following a century of anti-Asian racism and the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government forced more than 120,000 Japanese Americans into detainment camps.

Survivors want the world to remember. usatoday.com/in-depth/news/…

Survivors want the world to remember. usatoday.com/in-depth/news/…

Two-thirds of the people interned during WWII were American citizens. They were stripped of their homes, businesses, and civil rights, but were never accused of a crime or collaboration with the Japanese military.

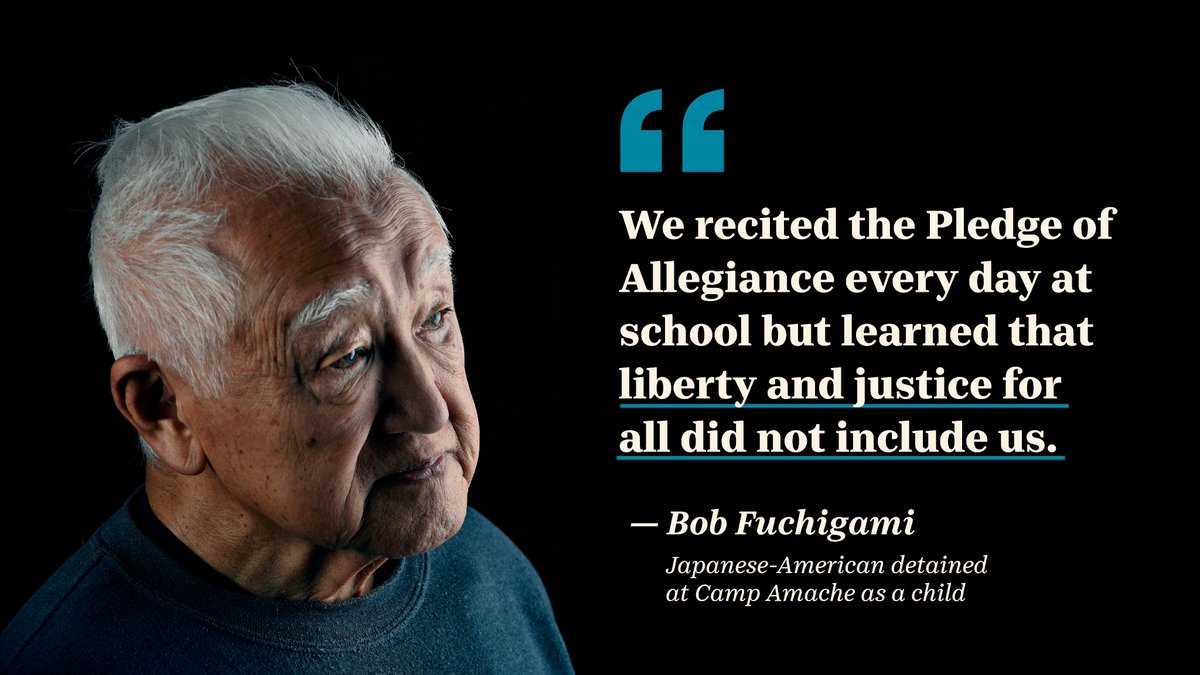

The "relocation" swept up immigrants and citizens alike — including @GeorgeTakei, who was 5, and Bob Fuchigami, who was 11 at the time. Their families and thousands of others were detained in horse stables for weeks before being herded onto a train.

📸: AP

📸: AP

In a desolate corner of Colorado, the US government hastily erected Camp Amache where 7,500 detainees would live out the remainder of World War II unless they volunteered for the front lines.

📸: AP

📸: AP

Now 91, Fuchigami is part of a shrinking generation of Japanese Americans who have kept alive the story of Colorado's Camp Amache and the nine other camps.

📸: AP

📸: AP

They worry that unless the United States confronts its racist past, it will inevitably repeat some of the mistakes of that era as a new wave of anti-Asian hate festers and anti-immigrant rhetoric ramps up.

Congress is considering legislation to make Amache a national historic site. Backers are hopeful that formal recognition will help tell the story of both the detention center and the people forced to live there.

📸: Helen H. Richardson, @denverpost via Getty Images

📸: Helen H. Richardson, @denverpost via Getty Images

@denverpost Read more stories that have ‘Never Been Told' at USATODAY.com neverbeentold.usatoday.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh