What does a Catholic chapel in the Cotswolds have in common with an Anglican church in the mountains of Cyprus?

Come with us on a journey from Brownshill to Troodos to find out …

Come with us on a journey from Brownshill to Troodos to find out …

In the late 1920s, Bertha Kessler and Katherine Hudson founded a Catholic retreat at Brownshill, in the Cotswolds, for people suffering from mental illness. They were inspired to build a chapel there, overlooking the Golden Valley.

They took their modest budget to W.D. Caröe, architect to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. At 73, he had already designed 30 Anglican and non-conformist churches. The distinctive church he created at Brownshill — along with its furnishings — was eclectic, yet unpretentious ...

St Mary of the Angels’, consecrated in 1937, is a Romanesque building with a roof of Cotswold slate, a Neo-Norman chancel arch, Swedish-influenced woodwork in the gallery, and a Byzantine apse!

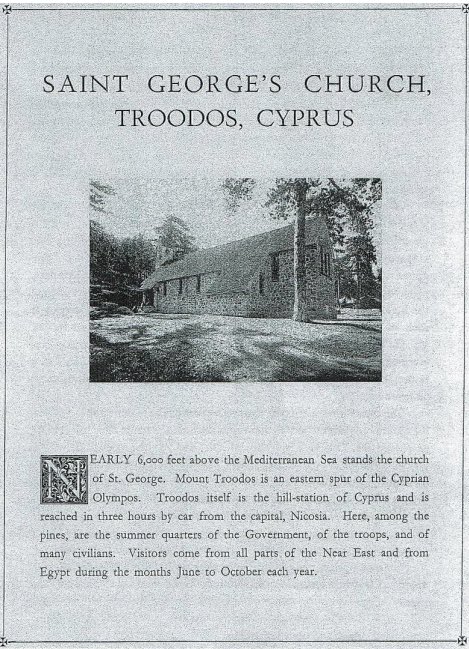

The Byzantine touches at Brownshill may well have been inspired by Caröe's previous project, another unusual commission. He had been the architect of St George-in-the-Forest — an Anglican chapel in Cyprus's Troodos mountains, 6000 feet above the Mediterranean sea.

The first request to build an Anglican church at Troodos was presented to Cyprus's governor and to the Bishop of the Diocese (Jerusalem) in 1927, Cyprus was at the time a British Crown Colony, and Troodos was the summer quarters of the government, troops and many civilians.

The military detachment there had been using a recreation room for services, which was inconvenient and unsuitable. A simple building of wood or corrugated iron was first proposed. However, in spring 1928, an invitation was sent to Caröe, who had spent the past winter in Cyprus.

He agreed to design a new church, at no charge. A site was soon chosen near Troodos village, in a forest of pine trees. It’s close to numerous historic Byzantine churches and monasteries, and the peak of Mount Olympus —mythical home of the Gods of Ancient Greece.

Caröe's design was for an Anglican-style church, but with consideration for the local environment and Cyprus's rich heritage. Built from mountain stones, it included a steep roof to allow snow to fall off.

As at Brownshill, Caröe designed the furnishings himself, some made of local materials, such as the altar of Cyprus cedar wood. Chairs and a piano were brought up from Nicosia, and an 18th Century icon of St. George beautifies the building.

By the time that the church opened in 1931 (when this church guide was made), Caröe must have already been working on his designs for the chapel at Brownshill.

St George-in-the-forest still serves Cyprus's English-speaking community, and is part of St. Paul’s Anglican Cathedral in Nicosia. Regular services are held outside of winter months, and Nine Lessons & Carols, with mince pies and mulled wine, in December.

We are grateful to Bill Grundy, Lay Reader of St Paul's and St George-in-the-Forest, for photographs of St George's church.

Learn more about St George-in-the-Forest, Troodos: bit.ly/3sRTZsF

Learn more about St George-in-the-Forest, Troodos: bit.ly/3sRTZsF

St Mary of the Angels', Brownshill in Gloucestershire was Caröe’s only Catholic church, and it was to be his last. He died just a year after it opened.

This serene chapel has been in our care since 2011. Find out more:

friendsoffriendlesschurches.org.uk/church/st-mary…

This serene chapel has been in our care since 2011. Find out more:

friendsoffriendlesschurches.org.uk/church/st-mary…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh