3 theses on the Russian-Ukrainian war:

1. Putin's decision to start the war on Ukraine isn't foreign policy. It's domestic one. Putin first consolidated his power through the war in 1999-2000 and it worked. So he repeated this trick every time his popularity started waning🧵

1. Putin's decision to start the war on Ukraine isn't foreign policy. It's domestic one. Putin first consolidated his power through the war in 1999-2000 and it worked. So he repeated this trick every time his popularity started waning🧵

Putin was confirmed as the Prime Minister on 16 August 1999. By that point Yeltsin chose him as a successor and Putin controlled intelligence. But he still had to stand on elections - and he was unknown. His rate of approval was between 3-4% because ppl didn't recognise his face

Just two weeks later apartment bombings started. Since September 4, a number of residential houses in Moscow, Volgodonsk, Buinaksk were blown up. More than 300 people died, 1700 were wounded. Putin accused Chechen terrorists in these attacks and invaded the separatist region

He won. In the course of the war he built his image as a tough victorious military leader. And Russian public opinion likes victorious military leaders. By the end of the year with the Chechen resistance largely crushed, he became very electable. That's how he became a President

Of course, the entire story with so timely blown up houses looked kinda shady. There were certain suspicions regarding who really organised these attacks, especially in the context of the Ryazan case

With all these explosions, the country became vigilant. On September 22 Alexey Kartofelnikov living on Novoselov 14/16 in Ryazan noticed a strange white car parked near their residential building. Its passengers took several bags and brought them into the basement of the house

After the strangers left, locals called the police. Police came and found several large bags from sugar - with a detonator. People were evacuated and the police expertise showed that the bags contain hexagon. Next day it became the national news - the media were still free

Prime Minister Putin congratulated them with preventing a terrorist attack. The same night police (police is MVD - different from FSB) arrested two suspects. To their surprise they showed the FSB IDs. Ofc Moscow HQ of FSB called the police and ordered to release their agents

Next day Putin gave a different version. Now he said that those were simply the trainings, the manoeuvres. The FSB was learning how to prevent terror attacks and these bags contained regular sugar. The detonators were fake

It all sounded shady. But the military planes were already raising Grozny to the ground. Successful invasion that followed changed the electoral balance completely. In August 1999 2% voters would vote for Putin, in 2000 - 53% did. Russian people love victorious wars

So, it worked. And that's how the institutional inertia dynamics commence. Whatever worked out in the past, will likely work out again. So why bother with making up new ideas if older ones are completely reliable? And indeed, reliable they were

In 2010s Putin was clearly losing popularity. Fraud on the parliamentary elections of 2011 triggered the largest street protests since Putin came to power. That was a bad marker. Economy was rising, quality of life improving. And many were still angry

But streets protests could be ascribed to a politicised minority, whereas silent majority supported him. That's why he confidently came to a boxing championate to give a speech, with the federal TV broadcasting it in real time. And he was booed with millions people watching

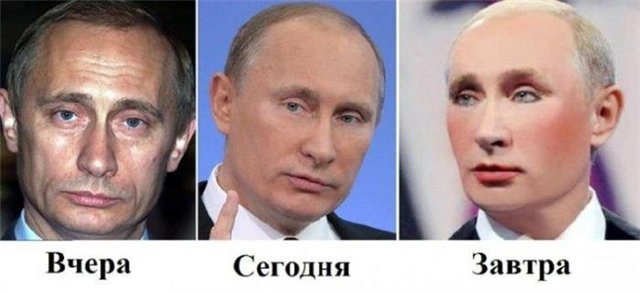

That was a heavy blow. He came to power as a victorious military leader. But now, 11 years later, ppl didn't recognise him as such. They saw him as a pathetic gerontocrat with too much botox fillings. He became a joke. So he had to take urgent action to be treated seriously again

His popularity falling, he had to restore his image as a serious leader. How? Well, by winning wars. Again, he initially built his legitimacy through a military victory, so why not do it again? Thus Russia engages into wars: Syria, Ukraine, Africa. Domestic policy by other means

So the real audience of this play are neither Ukrainians, nor Westerners. It's Russians. Of course many won't wholeheartedly support the war. But it will make them take Putin seriously. And for Putin it's much better to be regarded as bloody and merciless, rather than ridiculous

2. Many in the West exaggerate how robust the Putin's regime is. It's not only dependent on Western technologies and imports, it also can't decrease its dependence without a renegotiation of power balance. Which means it exists only as long as the West doesn't take action

Infrastructure-wise there is one thing it's doing well - building and maintaining communications for exporting raw materials. Railways, pipelines, seaports

And yet, sanctions obstruct development of new oil or gas deposits. There are new deposits introduced, but they don't compensate the depletion. Theoretically Russia has huge deposits, but they're primarily on Arctic shelf and Russia lacks the technology to extract them alone

Russia is not the USSR. The USSR was a theocracy legitimised through technological progress, which valued scientists and engineers highly. Modern Russia doesn't. Consider salaries which state corporation offers to aerospace engineers - kinda 150 usd/month

That's important to keep in mind. Unlike USSR, Russia doesn't value people who produce stuff. It's not prestigious, it doesn't pay. So whoever can leave to the IT and work for international market directly, will do it. There's huge negative selection in production of hardware

Which means that Russian industry, including military, is highly dependent upon Western technologies and equipment. Precision manufacturing is done on German, Swiss, Italian machines. Production of literally anything complicated continues only as long as it is allowed to continue

3. What will be the result of this war? That largely depends on Western, primarily American reaction. If Putin manages to win a small victorious war again and get away with that, it will not only increase his authority but trigger tons of terrirotiral conflicts all over the world

Let's be honest, in most countries there're groups who believe that their neighbours occupy a piece of our sacred land illegitimately. That's very typical feeling and usually it's mutual. The only reason why wars over the land don't happen more frequently is the fear of reprisals

If this invasion succeeds and Putin gets away with it, this will trigger a chain of imitators waging their small victorious wars all over the world. More powerful powers than Russia will certainly do, less powerful ones will try their chance, too. That will be a very bloody era

Paradoxically enough, even the military defeat of Russia is not necessary to prevent that scenario. Simply Putin losing his power would be enough as a warning. And counterintuitively, that would likely result naturally if he doesn't achieve a quick victory

There's a big difference between an easy war and a hard war. An easy war makes regime stronger because it achieves victory without having to transform. But a hard war will transform it. The longer WWI lasted, the more the real power over Germany flowed from Kaiser to Ludendorff

Russia plays hard. But hard war is incompatible with the state security rule. They aren't guys who do stuff, they are the guys who find wrongdoings in the work of others. Critics, not doers. So once the war becomes existential, power will start flipping from their hands. End of🧵

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh