We have just released two preprints on the origin of SARS-CoV-2:

1. "The Huanan market was the epicenter of SARS-CoV-2 emergence"

zenodo.org/record/6299116…

1. "The Huanan market was the epicenter of SARS-CoV-2 emergence"

zenodo.org/record/6299116…

&

2. "SARS-CoV-2 emergence very likely resulted from at least two zoonotic events"

zenodo.org/record/6291628

2. "SARS-CoV-2 emergence very likely resulted from at least two zoonotic events"

zenodo.org/record/6291628

Tremendous team effort:

Paper 1.

Led by @K_G_Andersen and me:

@josh__levy @LrnM9 @acritschristoph @jepekar @stgoldst @angie Rasmussen @MOUGK @WildCRU_Ox @MarionKoopmans @suchard_group Joel Wertheim @LemeyLab @robertson_lab Bob Garry @edwardcholmes @arambaut

Paper 1.

Led by @K_G_Andersen and me:

@josh__levy @LrnM9 @acritschristoph @jepekar @stgoldst @angie Rasmussen @MOUGK @WildCRU_Ox @MarionKoopmans @suchard_group Joel Wertheim @LemeyLab @robertson_lab Bob Garry @edwardcholmes @arambaut

Paper 2.

Led by @jepekar, @suchard_group, @K_G_Andersen, me, and Joel Wertheim:

@afmagee42, @EdythParker, @niemasd, @gkay92, @TanyaVasylyeva, @acritschristoph, @josh__levy, @LrnM9, @suchard_group, @edwardcholmes, @arambaut, @akaEscapePlan, @KatherineIz

Led by @jepekar, @suchard_group, @K_G_Andersen, me, and Joel Wertheim:

@afmagee42, @EdythParker, @niemasd, @gkay92, @TanyaVasylyeva, @acritschristoph, @josh__levy, @LrnM9, @suchard_group, @edwardcholmes, @arambaut, @akaEscapePlan, @KatherineIz

Paper 1: Given that the Huanan market is the only location in Wuhan for which prior epidemiological and geographic evidence exists that it might have been the site of origin of the epidemic, we set out to test this hypothesis statistically.

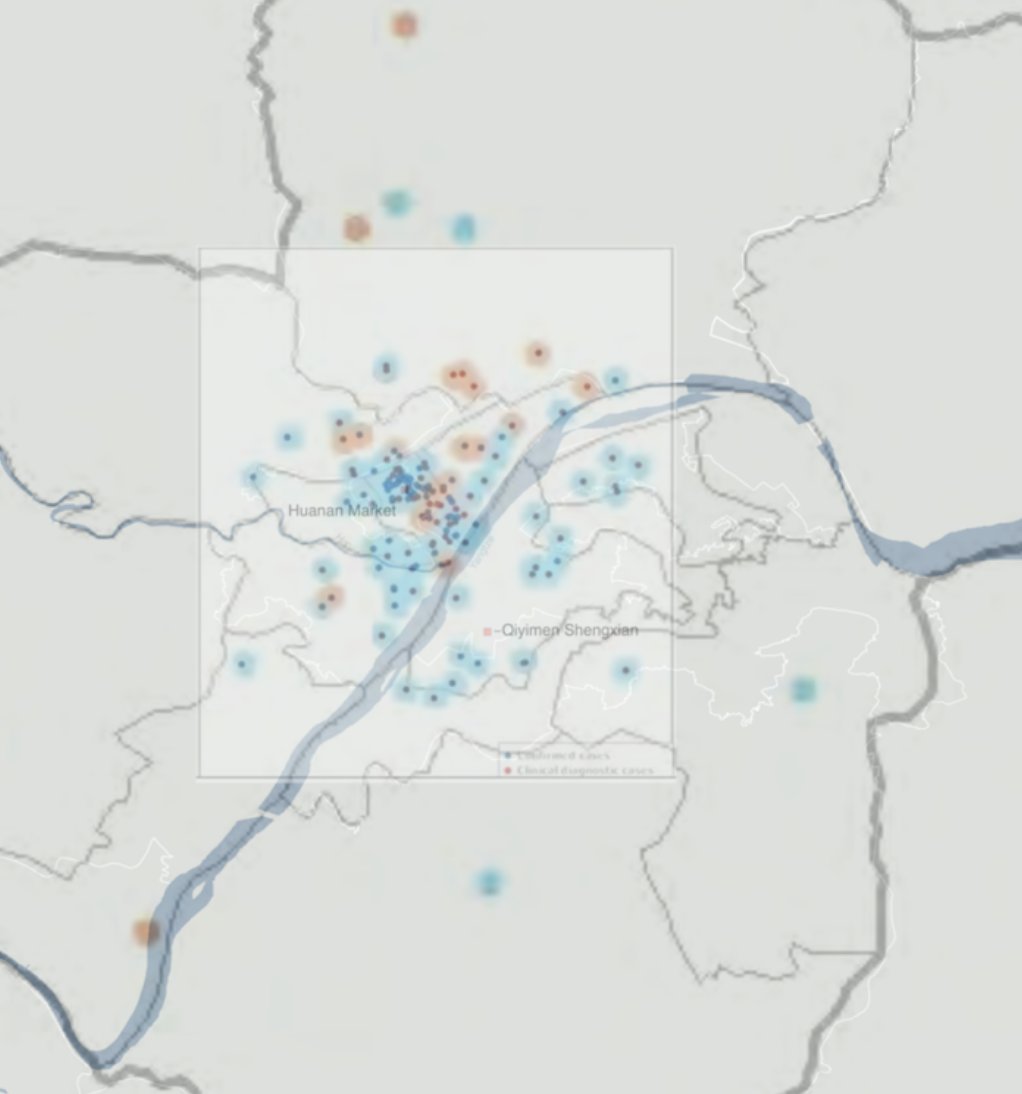

We used the maps in the WHO mission's report on the origin of SARS-CoV-2 to extract latitude and longitude for most of the known COVID-19 cases from Wuhan with symptom onset in December 2019.

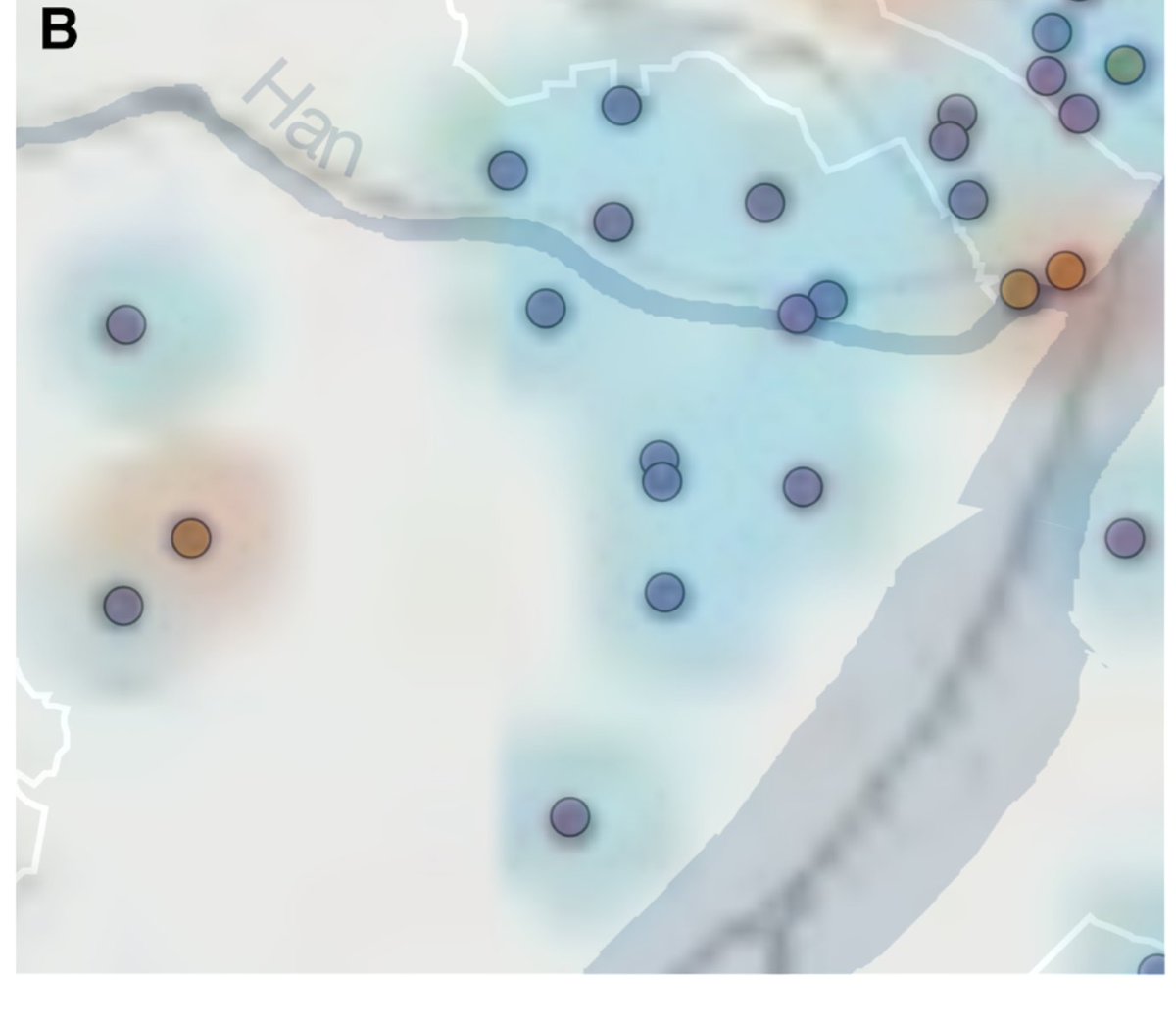

And they allowed us to look at the density of cases in Wuhan early in the pandemic. Even though there is some noise in the location data, Huanan market sits right in the highest density region.

More interestingly, when you look at *only those cases with no known link to the Huanan market* you still see this pattern. This is a clear indication that community transmission started at the market.

Striking contrast with cases from later in the epidemic, when the virus was more widespread in Wuhan. In early 2020, you see cases all through central Wuhan, on both sides of the Yangtze.

We found that cases in December were both nearer to, and more centered on, the Huanan market than could be expected given either the population density distribution of Wuhan, or the spatial distribution of COVID cases later in the the epidemic. Its epicenter was at the market

Surprisingly, uses cases for which we could link a location and genome sequence - and this is one of *the* most important findings in this paper - we found that so-called lineage A viruses (the ones that had not been found at the market)....

This strongly suggests that BOTH lineage B and lineage A arose at the Huanan market and began spreading into the Wuhan residential community from there. More on that in a bit.

Let's shift over to Paper 1 at this point. In that paper, too, lineage A and lineage B, the two main lineages of the virus circulating in China in the early part of the pandemic, become super important.

We collated more than 700 complete genomes of SARS-CoV-2..

We collated more than 700 complete genomes of SARS-CoV-2..

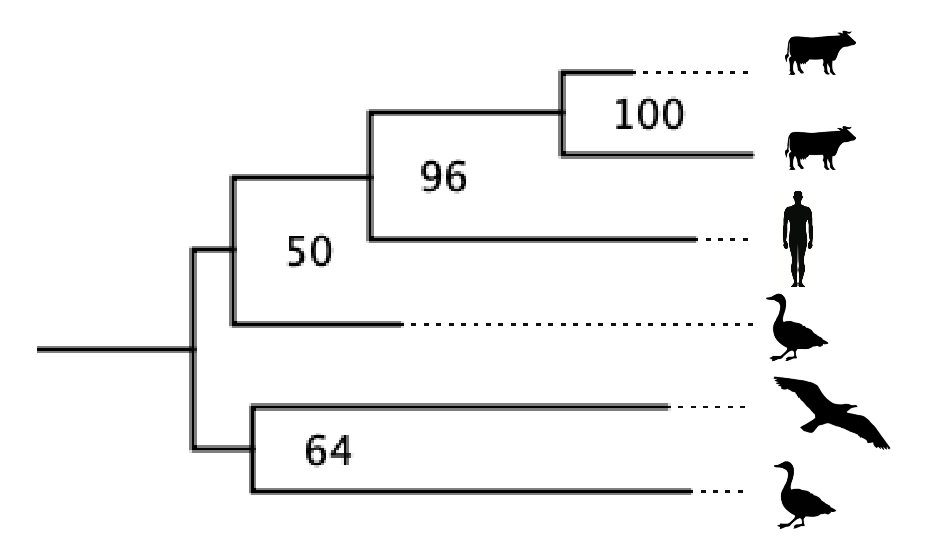

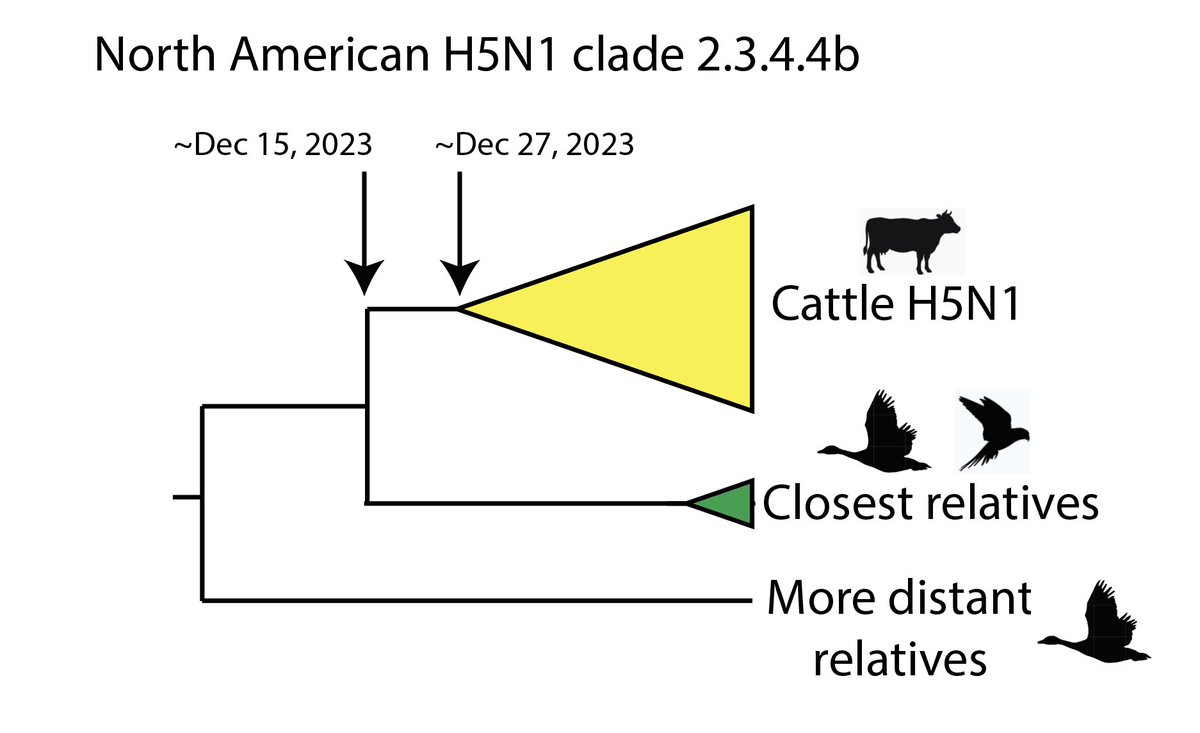

...from December 2019 up until mid February of 2020. About 1/3 are lineage A and 2/3 lineage B. We find that the were very likely at least *two* origins SARS-CoV-2 - one for lineage A and one for lineage B. The patterns in the phylogeny are the giveaway.

And the lineage A likely postdated lineage B even though it is likely more similar to the bat progenitor virus. And the earliest jump (likely but not certainly B) was probably in LATE November and NO EARLIER than November.

Combining the findings of the two papers, we thus concluded that these two cross-species transmission events happened at the Huanan market (more on what we learned about within the market in a bit).

And we suspected that it was because A happened perhaps a week or two....

And we suspected that it was because A happened perhaps a week or two....

after B, that that was both why A was less prevalent (so far unseen) at the market and why A was less prevalent in the epidemic - even though it is more bat-like.

And then...

And then...

Well, let me come to the "And then..." part later. Back to within the market.

(but it has to do with this preprint posted yesterday:

researchsquare.com/article/rs-137…)

(but it has to do with this preprint posted yesterday:

researchsquare.com/article/rs-137…)

We show that, contrary to what some may have believed, wished to believe or asserted, live mammals susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 were present at the Huanan market in the crucial months of November and December 2019.

Digging deeper, we found a report from the China CDC, who had done testing of environmental samples (swabs of surfaces) in the market, that provided details missing in the WHO report. Like, if a stall was "positive", how many samples were positive there...

And what surface were they from? We also were able to go through business registries and things like record of fines for the sales of illegal wildlife, to show that more businesses that realized during the WHO study had been selling live mammals in late 2019...

While there are caveats we mention in the preprint (please read it) and neither this preprint nor the other have been published post peer review, the location of stalls selling live mammals was highly predictive of where environmental positives were located.

One striking (to us at least) finding: one stall had 5 environmental positive samples for very animal-centric surfaces, including a "metal cage in a back room". And the was one of the stalls we know was selling live mammals illegally in late 2019. But, there's more...

It happened to be a stall that one of us, @edwardcholmes, had visited 5 years before the pandemic, and where he had taken this photo of a raccoon dog.

@edwardcholmes As we conclude in the Discussion:

@edwardcholmes "Together, these analyses provide dispositive evidence for the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 via the live wildlife trade and identify the Huanan market as the unambiguous epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic."

@edwardcholmes Coda: As we were doing the final quality checks on these papers yesterday, this preprint by George Gao et al posted.

And it found that lineage A was indeed found at the Huanan market, in a swab from a glove (sample A20).

researchsquare.com/article/rs-137…

And it found that lineage A was indeed found at the Huanan market, in a swab from a glove (sample A20).

researchsquare.com/article/rs-137…

@edwardcholmes We end Paper 1 with this:

"Note added in proof: A recent preprint from Gao et al. (50) confirms the authenticity of the CCDC report and reported the presence of the ‘A’ lineage of SARS-CoV-2 from an environmental sample at the Huanan market, consistent with a separate...

"Note added in proof: A recent preprint from Gao et al. (50) confirms the authenticity of the CCDC report and reported the presence of the ‘A’ lineage of SARS-CoV-2 from an environmental sample at the Huanan market, consistent with a separate...

@edwardcholmes "introduction of this lineage at the market. Further, this preprint reported additional positive environmental samples in the southwestern area of the market selling live animals...

@edwardcholmes "These findings are strongly consistent with those presented here, corroborating our conclusion that the Huanan market was the epicenter of SARS-CoV-2 emergence and the site of origin of the COVID-19 pandemic."

@edwardcholmes And back to Paper 2. Again I want to emphasize how recently this pandemic appears to have emerged. @pekar's simulations and molecular clock dating estimate put the earliest of the (at least) two successful introductions into humans in late November.

@edwardcholmes @pekar And if you look at the estimates of the number of people infected through time, at the point when the earliest patient linked to the Huanan market fell ill, on Dec 10, there were probably only around 10 people on the planet infected with the virus, and fewer than 70.

@edwardcholmes @pekar We certainly do not know every person early on who was infected. Just given the 174 hospitalized cases with onset in December, and given that there are roughly 13 milder, unhospitalized cases for every one that end up in the hospital, we know there must have been...

@edwardcholmes @pekar more than 2000 infected people in December. But, equally, for every one we know about at the market, there are, say, 13 we didn't, so the unascertained cases don't mean you can reasonably say that there weren't a large proportion of people infected at the market.

@edwardcholmes @pekar More importantly, the spatial distribution of the cases NOT LINKED to the market shows they tended to live close to and centered on the market. So that means the unascertained cases must also share this pattern.

@edwardcholmes @pekar And at any rate, our estimates for how many people were infected by December 10 (~10) include both ascertained an unascertained infections.

@edwardcholmes @pekar We will soon post a revised version of Paper 1 that corrects an error. We referred to location data from a Weibo COVID-19 help app as "COVID-19 case locations" or "COVID-19 cases". Since these are not confirmed COVID-19 cases, we will change to "Weibo location data" or similar.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh