Three Greek poetic epithets describing Ares, God of War:

Λαοσσοος- Laossoos: "He Who Rallies Men"

Μιαιφονος- Miaiphonos: "Blood-stained"

Ανδρειφοντης- Andreiphontês: "Destroyer of Men"

-Bronze Corinthian Helmet [detail] 5th c. BC

Λαοσσοος- Laossoos: "He Who Rallies Men"

Μιαιφονος- Miaiphonos: "Blood-stained"

Ανδρειφοντης- Andreiphontês: "Destroyer of Men"

-Bronze Corinthian Helmet [detail] 5th c. BC

These two Homeric epithets for Ares: Areiphatos & Areiktamenos mean respectively "killed by Ares" & "killed in War", i.e. Ares ultimately embodies every death in war.

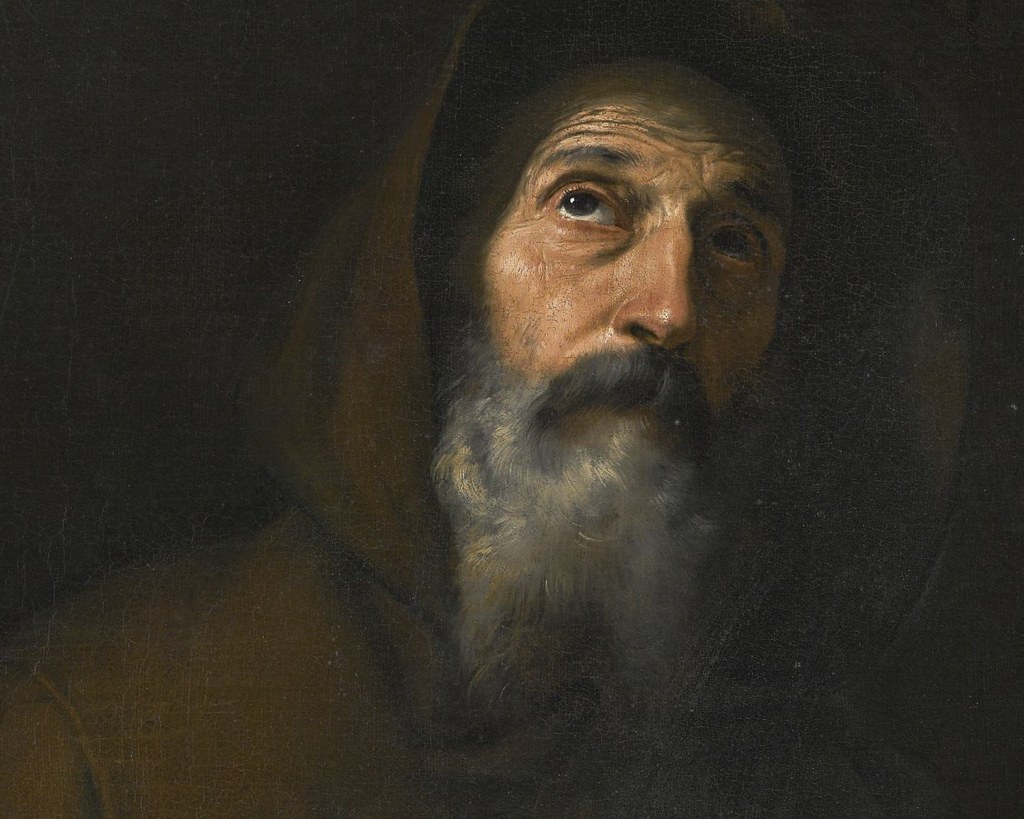

Roman bronze statue of Mars, God of War [face detail] 2nd century AD -at Gaziantep Museum, Turkey [1]

In the Iliad, Trojan warrior Pedaeus is killed by the Greek spearman Meges in arguably the most strikingly graphic of Homer's war death descriptions.

The above Homeric passage is from Book V of 'The Iliad' translated by Robert Fagles [1]

In Book V of the Iliad, another Homer's graphic war death description when the Cretan commander Meriones spears Trojan warrior Phereclus.

The above Iliad's death description of Meriones spearing Trojan Phereclus is surprising in his anatomical precision, meaning a first-hand knowledge according to this note in "A Companion to the Iliad" edited by Malcolm M. Willcock.

Homer's Power of Linguistic Visualization in the Iliad:

The series of deaths in battles between Trojan & Greeks can be characterized as clinically objective yet underpinned by a deep feeling, that is a pathos at the inexorable fleetingness of human life.

The series of deaths in battles between Trojan & Greeks can be characterized as clinically objective yet underpinned by a deep feeling, that is a pathos at the inexorable fleetingness of human life.

Greek warrior killing a Trojan or perhaps a Trojan warrior killing a Greek? from a frieze on the tomb of a Lycian prince, the Heroon of Goelbasi-Trysa, ca. 380 BC (Turkey) [1]

Homer's power of graphic visualization through language was admired throughout antiquity. Byzantine scholar Eustathios of Thessalonike said Homer's vivid scenes were "as if painted in a picture"

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh