In January’s Parliamentary sitting, members debated the transition toward a green economy. It will also feature in the budget and Committee of Supply debates, currently ongoing. The issue is urgent and important, not least because steps need to taken today to get us there. (1/n)

I’m not usually a Debbie Downer, but my contributions to the debate were mostly cautionary. I spoke about the importance of measuring progress, and warned about how green financing wasn’t some magic bullet, as well as risks from greenwashing. (2/n)

We’ve heard about how the financial sector can make a massive difference to getting us to the promised land of limiting climate change. Of course, finance is important (I teach, research, and practice it, after all!) but not quite sufficient. (3/n)

The reason is that the premise (and promise?) of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) is that it is possible to earn solid returns, while investing only in good-for-the-world companies. To do well while doing good—who would object? (4/n)

Alas, the reality is that most ESG funds underperform their plain-vanilla cousins that just track the index. Which sounds tragic, but actually, that is precisely the point. We want such green funds to, on average, do more poorly than those that aren’t green. (5/n)

Why? Because the flip side of low returns in “green” funds is high returns in “brown ones. And since high returns to investors means higher cost of capital for companies, this means that such firms will find it harder to do business. (6/n)

That means that they are likely to either pollute less (become more green), or go out of business altogether. Either way, we gradually shift the economy toward more sustainable businesses and business practices, which is what we want. We need to develop our natural capital. (7/n)

One caveat: not all ESG investments must do poorly, of course. If you put money in a company that will end up dominating a space (that’s what many hope Tesla will do with electric vehicles), then you will certainly be amply rewarded. But winners are hard to find. (8/n)

More generally, labeling something (including finance) “green” runs the risk of greenwashing: clothing actions in the veneer of the environment, but not really doing much that would truly move the needle to true sustainability. (9/n)

One notorious example has to do with carbon offset credits. The idea is appealing; not every firm is able to slash their emissions, and so these companies can purchase forested land—which act as carbon sinks—to net out their carbon footprint. (10/n)

The problem is that many such lands exist in developing countries, where standards for ensuring that the deal is adhered to aren’t always the best. What’s worse, the purchased land may have never been slated to be cut down, anyway! (11/n)

The abuse of such schemes means, more often than not, that they become a placebo for genuine action, and the planet isn’t any better as a result (and if companies use this as a “license” to indulge in pollution, things may even deteriorate). (12/n)

Similar greenwashing examples occur with recycling. The last thing we want is for items we think are being recycled—especially those that are shipped thousands of miles to another country—end up in a landfill. (13/n)

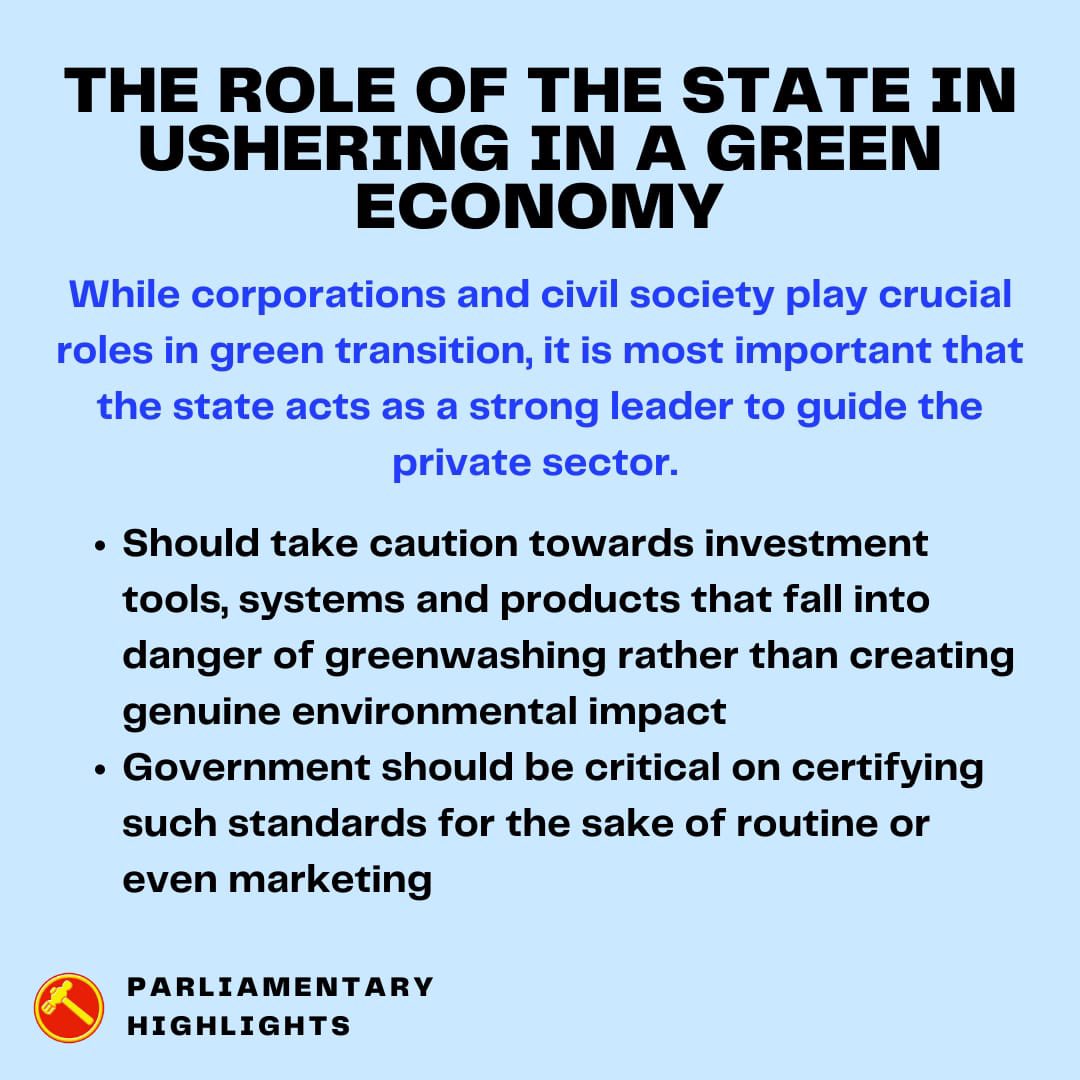

The bottom line is that we need to be aware that there could be a disconnect between our intentions, and actual outcomes, when it comes to policies meant to protect our planet. Such deviations are likely more common when profit concerns dominate. (14/n)

That’s why government programs—like ecolabeling and public-private partnerships—shouldn’t end up inadvertently lending a seal of approval to otherwise environmentally irresponsible companies. #makingyourvotecount (n/n)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh