Updated side-by-side scaled comparison of the 9th day of Iraq & Ukraine (R map by @TheStudyofWar).

By this point, the Army's V Corps had made it ~600 km along the Euphrates and were attacking Karbala; 1st Marine Division had crossed the river at Nasiriyah and progressed >200 km.

By this point, the Army's V Corps had made it ~600 km along the Euphrates and were attacking Karbala; 1st Marine Division had crossed the river at Nasiriyah and progressed >200 km.

https://twitter.com/bazaarofwar/status/1498119251672059909

@TheStudyofWar The closest comparison to the Marines' progress is the fighting at Kherson—like Nasiriyah, it guarded the crossing of a major river.

Kherson took 6 days to fall, Nasiriyah ~10. In both cases, other elements pushed ahead beforehand, but the Russians have only progressed ~80km...

Kherson took 6 days to fall, Nasiriyah ~10. In both cases, other elements pushed ahead beforehand, but the Russians have only progressed ~80km...

@TheStudyofWar In the Russian case, they had to secure another river crossing, at Mykolaiv on the Southern Bug (Pivdenny Buh).

They have also begun probing a second crossing at Voznesensk (map from militaryland.net), >200 km over the Dnieper.

They have also begun probing a second crossing at Voznesensk (map from militaryland.net), >200 km over the Dnieper.

https://twitter.com/NotWoofers/status/1499776584500269065

@TheStudyofWar The advance south of the Dnieper has been slower. In part this is because of fighting at Melitopol, which was over by 1 March, but the city was also bypassed by forces advancing along the coast and up to the river. Progress here has been >300 km past Mariupol (>30 km/day).

@TheStudyofWar This is about the same as the advances from the eastern border near Sumy to the outskirts of Kiev.

Meanwhile, progress to the west of Kiev has slowed as fighting in the suburbs and traffic jams in the logistics train delay progress.

Meanwhile, progress to the west of Kiev has slowed as fighting in the suburbs and traffic jams in the logistics train delay progress.

https://twitter.com/trbrtc/status/1499736489432961029

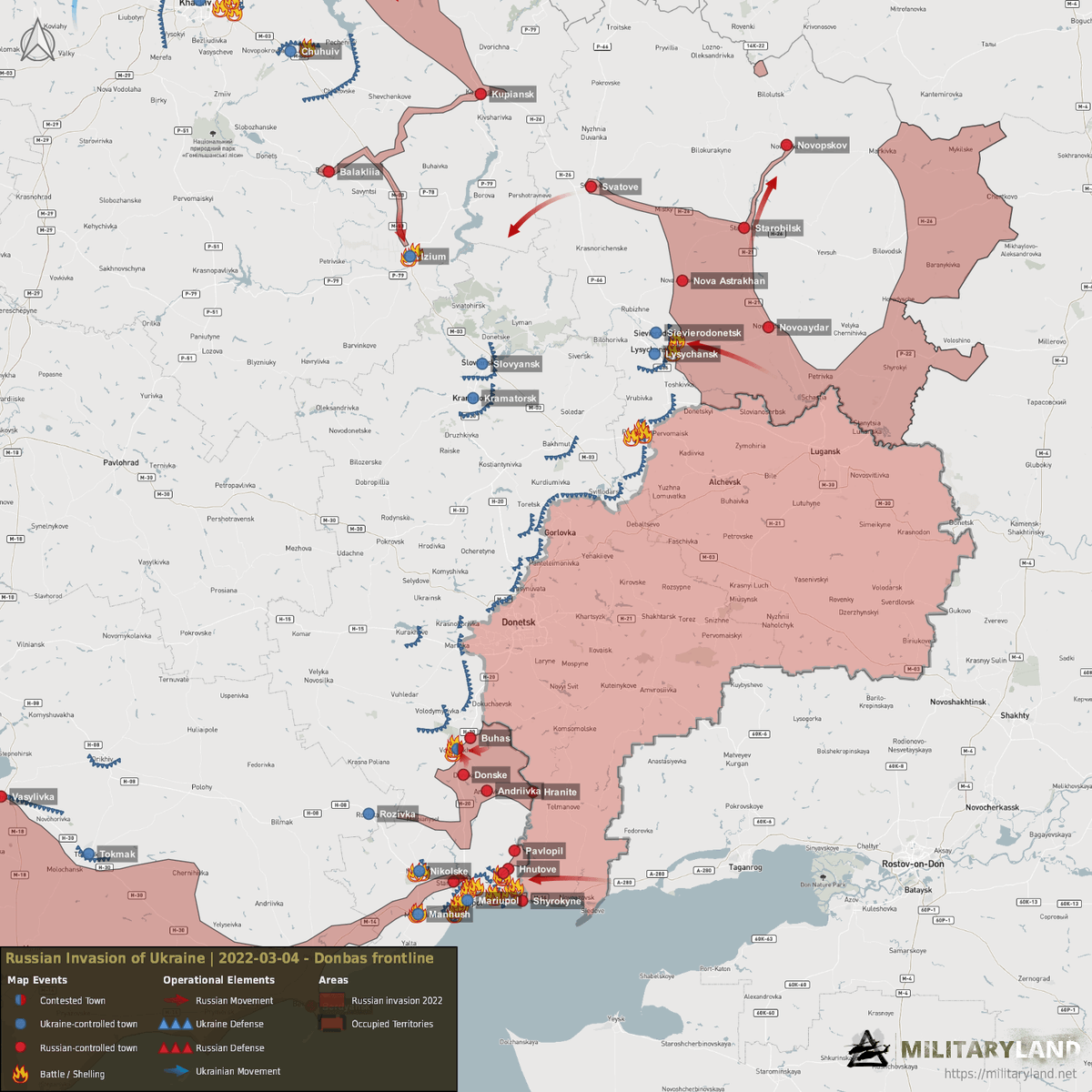

@TheStudyofWar The biggest story is in the east. As some Russian forces are besiege Kharkov, others have pushed past to attack the Ukrainian position at Izyum, a major road junction which will make it difficult for the Ukrainians to withdraw their forces in the Donbas.

https://twitter.com/bazaarofwar/status/1499756215840223232

@TheStudyofWar At the same time, the Russians seem intent on cutting off both the Dnieper crossings at Zaporizhzhia & Dnipro AND drawing a tighter cordon around the Donbas forces.

Which might explain....

Which might explain....

https://twitter.com/bazaarofwar/status/1498671983822839817

@TheStudyofWar ....the reported attempt to relieve Kharkov. EXTREMELY unlikely to achieve its stated goals, given the overwhelming firepower Russia has assembled there, but it might relieve the pressure on Izyum enough to allow withdrawal of the Donbas forces.

https://twitter.com/sentdefender/status/1499852381835698188

@TheStudyofWar The race is on for the withdrawal, if that is indeed what's intended. There are four major routes between the Donbas and the Dnipro/Zaporizhzhia crossings; the southern one has already been cut off in multiple places and the northern one is threatened at Izyum....

@TheStudyofWar ...so expect a race to Pokrovske and possibly Pavlograd. After that, the last major urban battle will be Dnipro.

@TheStudyofWar Around 45k soldiers from Ukraine's best units were stationed in the Donbas at the beginning of hostilities, so there is a lot at stake for both sides. So much so that we might expect Russia to increase its use of air, even in the face of air defenses.

https://twitter.com/bazaarofwar/status/1499042283341111296

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh