Just finished reading this old-ish gem by Herbert Simon (1992) that I strongly suggest reading for all interested in the epistemological foundations of behavioural sciences. Many key ideas are extremely clearly and convincingly laid down 1/n

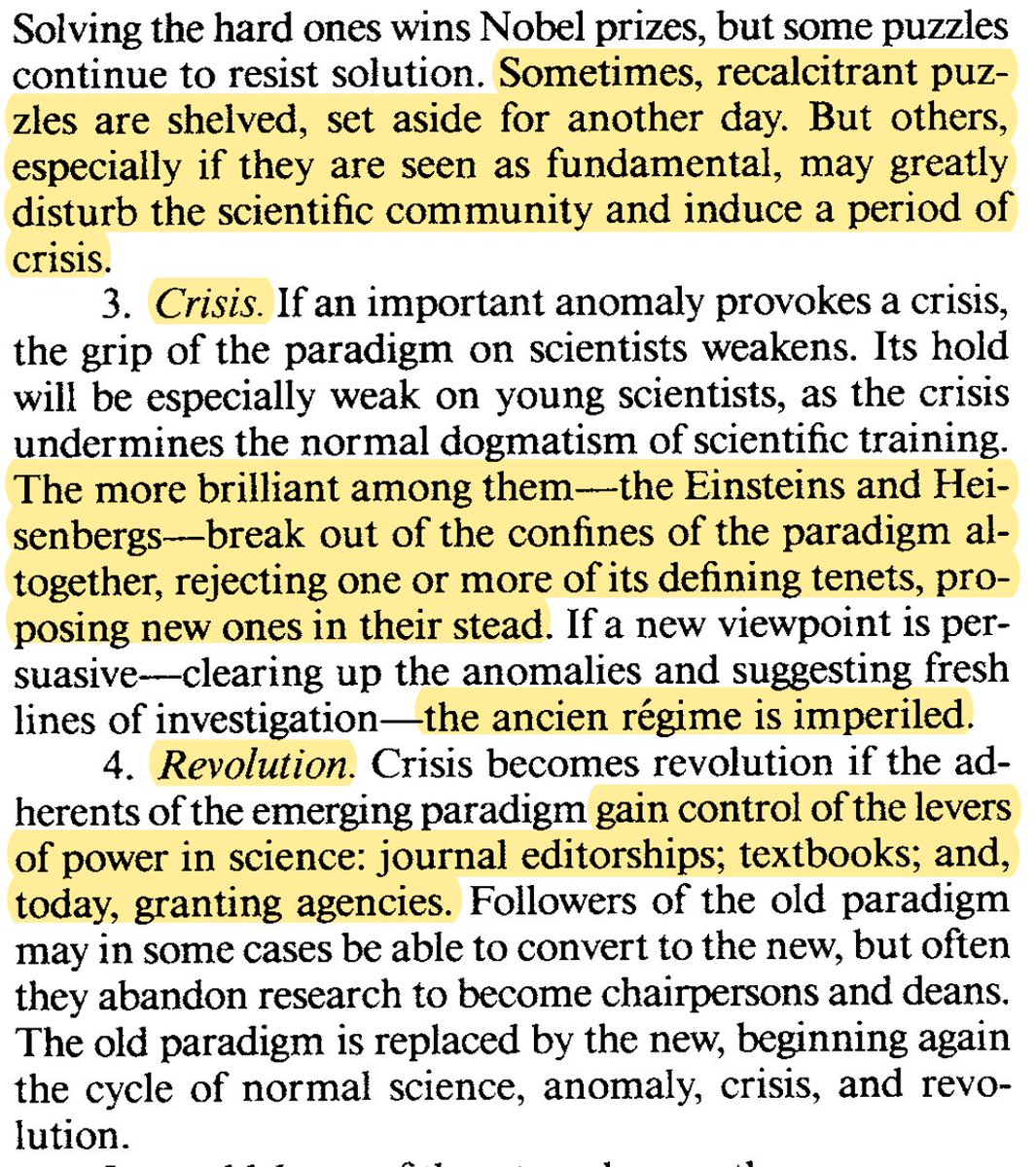

The first great thing to mention about the paper is that even one of the "fathers" of cognitive revolution did not believe that a cognitive revolution ever happened 2/n

I wrote about this topic in another thread about Leahey's great paper (link below). A cognitive "revolution" never happened: let's get over it. 3/n

https://x.com/StePalminteri/status/1460958701054050308?s=20&t=vp1L-jB_CL8KQRBMwigC2Q

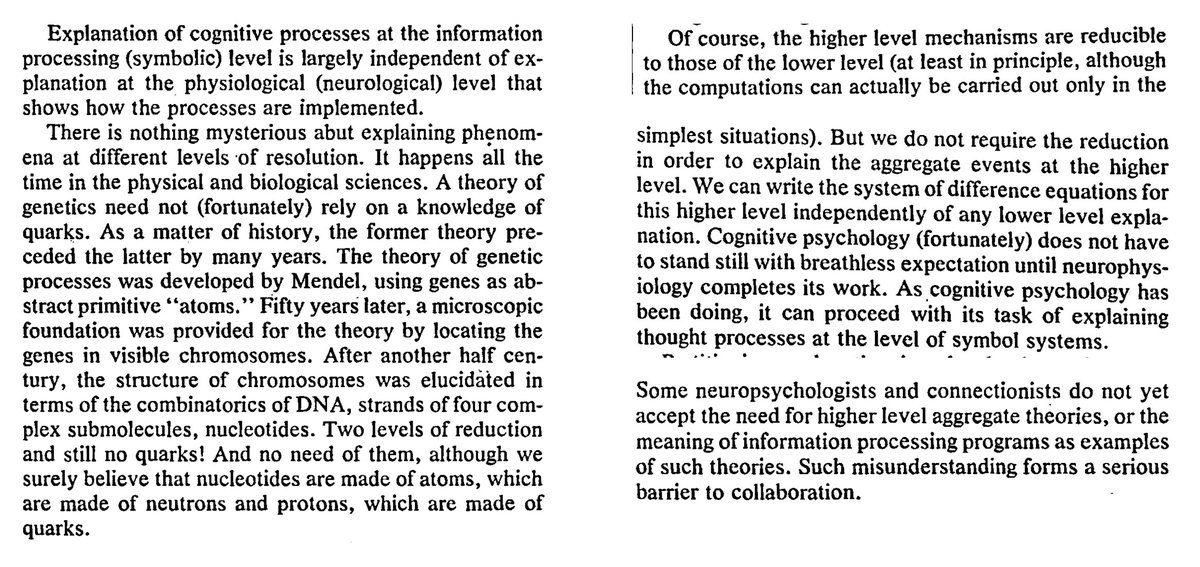

The second remarkable thing about the paper is one of the clearer defence of the anti-reductionist approach to understanding human cognition I have ever read (key passages below) 4/n

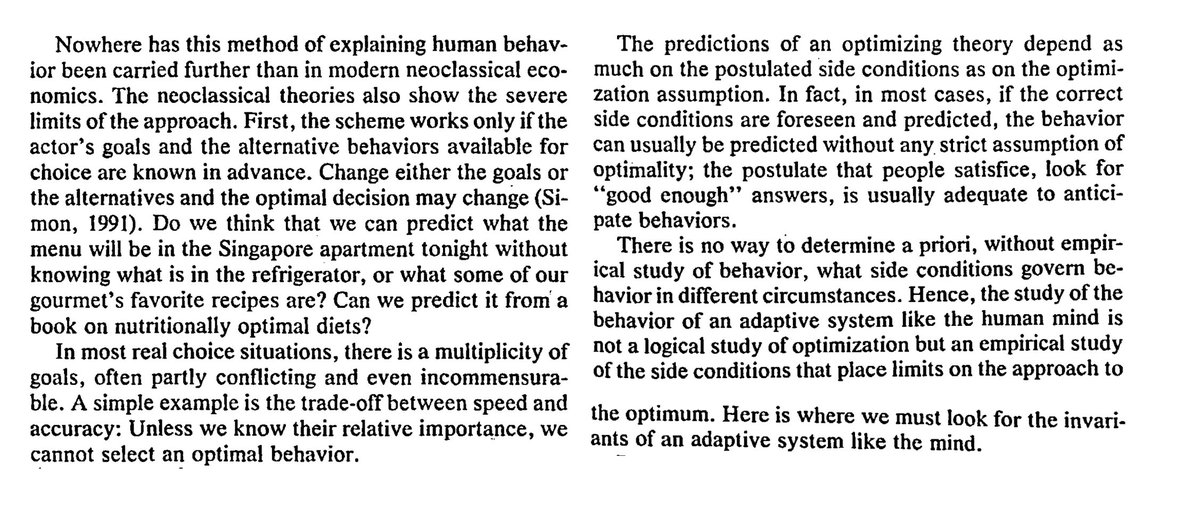

The third thing is a very clear illustration of the idea that normative principles (statistical or evolutionary) bear little heuristic values for discovering how the mind actually works, which is in essence an empirical endeavour 5/n

There are many other great things on the paper. It can be found here. journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/j.…

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh