1/8

A young woman presents with progressive dyspnea. You walk into the room and this is what you see.

What finding is present?

A young woman presents with progressive dyspnea. You walk into the room and this is what you see.

What finding is present?

2/8

Central cyanosis indicates the presence of hypoxemia. SPO2 by pulse oximetry is 80%. ABG on room air shows PaO2 of 40 mm Hg and PaCO2 of 30 mm Hg.

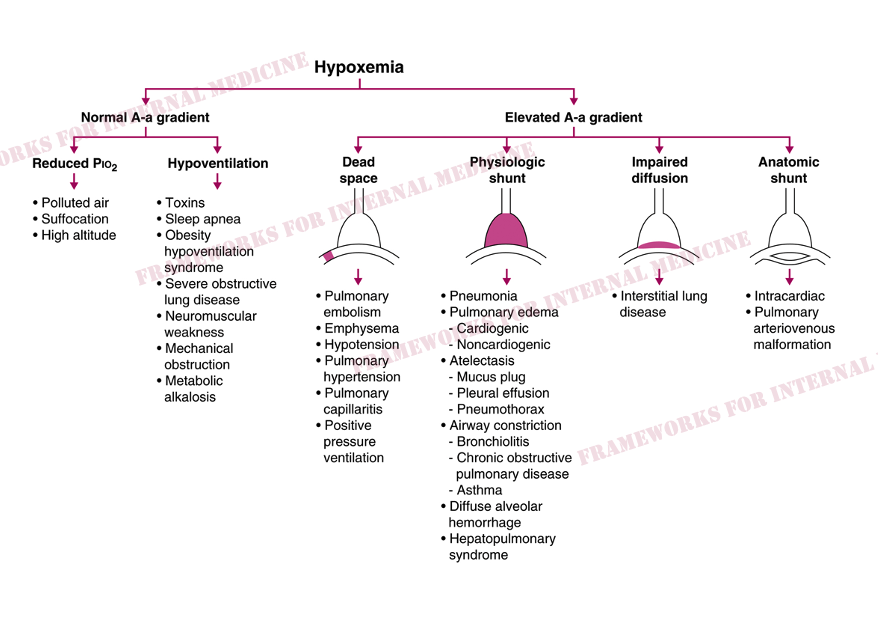

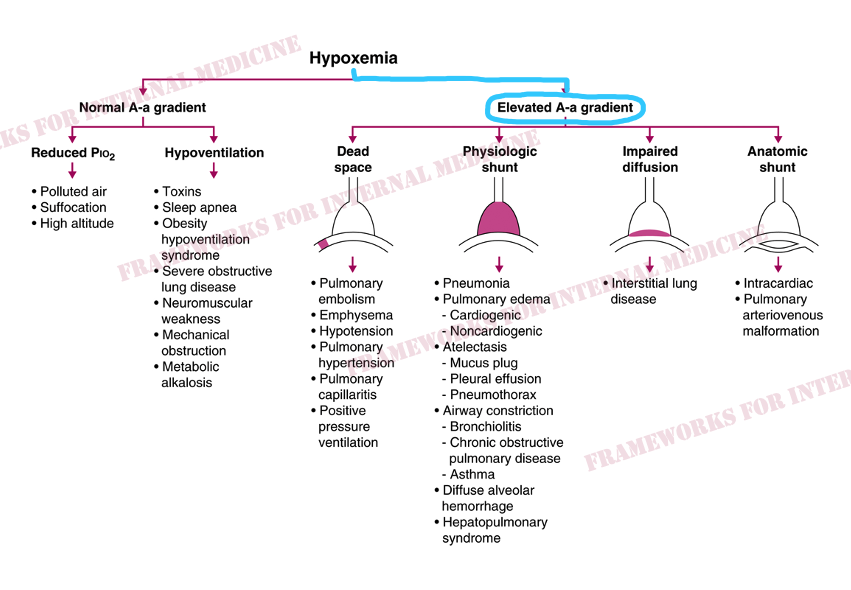

We reference our framework for hypoxemia to begin the process of narrowing our differential diagnosis.

Central cyanosis indicates the presence of hypoxemia. SPO2 by pulse oximetry is 80%. ABG on room air shows PaO2 of 40 mm Hg and PaCO2 of 30 mm Hg.

We reference our framework for hypoxemia to begin the process of narrowing our differential diagnosis.

3/8

The first thing we want to know is the A-a gradient.

A (from the alveolar gas equation) = 112 mm Hg

a (from the ABG) = 40 mm Hg

A-a = 112 - 40 = 72 mm Hg.

Elevated.

The first thing we want to know is the A-a gradient.

A (from the alveolar gas equation) = 112 mm Hg

a (from the ABG) = 40 mm Hg

A-a = 112 - 40 = 72 mm Hg.

Elevated.

4/8

Next we revisit the physical examination for more clues. There is profound peripheral cyanosis. But what else do you notice?

If you don't specifically look for this finding you might never notice it. "The eyes can't see what the mind doesn't know."

Next we revisit the physical examination for more clues. There is profound peripheral cyanosis. But what else do you notice?

If you don't specifically look for this finding you might never notice it. "The eyes can't see what the mind doesn't know."

6/8

The patient's precordial movement shown here is suggestive of an intracardiac shunt. @PeteSullivanPDx teaches that the chest can move in this way when blood travels from a higher pressure chamber to a lower pressure chamber. In this case, from the right to the left.

The patient's precordial movement shown here is suggestive of an intracardiac shunt. @PeteSullivanPDx teaches that the chest can move in this way when blood travels from a higher pressure chamber to a lower pressure chamber. In this case, from the right to the left.

7/8

Our diagnosis is confirmed with an echo with agitated saline contrast. Bubbles appear in the LV within 3 beats.

Bubbles are normally filtered by the lungs. They only appear in the L side of the heart if there is an intracardiac (few beats) or intrapulmonary shunt (>5 beats).

Our diagnosis is confirmed with an echo with agitated saline contrast. Bubbles appear in the LV within 3 beats.

Bubbles are normally filtered by the lungs. They only appear in the L side of the heart if there is an intracardiac (few beats) or intrapulmonary shunt (>5 beats).

8/8

We diagnosed an intracardiac shunt with our eyes, a Q-tip, and a few specific hypothesis-driven tests.

Physical exam plays a critical role in diagnosis.

For more cases: physicaldiagnosispdx.com/case-presentat…

Source of hypoxemia framework: amazon.com/Frameworks-Int…

We diagnosed an intracardiac shunt with our eyes, a Q-tip, and a few specific hypothesis-driven tests.

Physical exam plays a critical role in diagnosis.

For more cases: physicaldiagnosispdx.com/case-presentat…

Source of hypoxemia framework: amazon.com/Frameworks-Int…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh