My most recent article, "“A Well-Outfitted Militia: German-American Translations of the #SecondAmendment and Original Public Meaning," has been recommended for publication pending minor revisions.

This article stems from a previous thread of mine that I decided to develop a bit more, and here are the broad findings and what five German-American translations might tell us about original public understanding of the Second Amendment:

1. Even scholars who argue "collectivist/civic obligation" have noted that "well regulated" at the time meant "in good working order," not government oversight. The German translations (and original public understanding) confirm this.

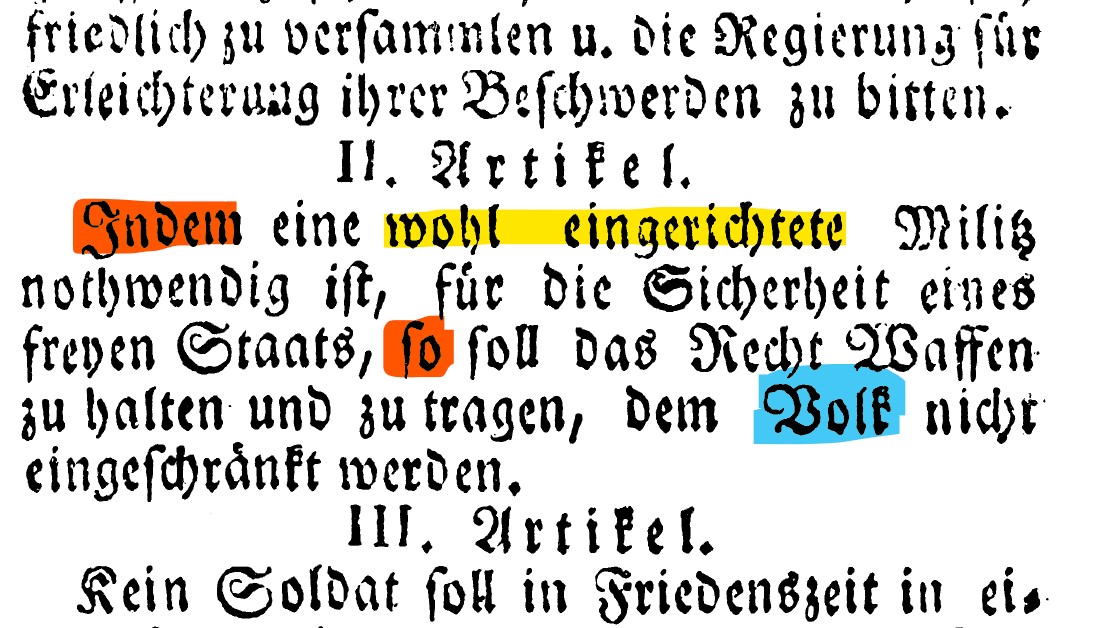

They use "wohl/gut eingerichtete" (well-furnished/equipped/outfitted) for "well regulated": . You'd use "gut eingerichtete" to describe a house you wanted to rent or how a ship was outfitted. I settled on "well-outfitted" rather than "well-equipped" or "well-furnished."

2. They translate "People" as "Volk," which by the Enlightenment had nationalist connotations in secular documents (such as the Constitution). Like the English original, it uses the same word for "People" as in the First and Fourth Amendments.

This means that the "militia" (as a concept/idea) was referring to the "whole [armed] people" rather than local or state militias enshrined in state laws (as collectivists argue). It's not meant to protect collective rights/militias but an individual right.

3. Supreme Court Justices Warren Burger and Antonin Scalia each wondered what would happen if you added "because" to the beginning of the amendment, to different logical conclusions. The translations offer conjunctions that are not "because."

They fix the clumsy English wording by including two conjunctions at the beginning of each clause: First, "Indem" (As/Whereas) or "Da" (Since) for the Militia Clause. I take this to mean that the Militia Clause is meant as a permanent axiom: the Framers believed that a Militia

(an armed national people) is the best defense of a national people's liberties. The second conjunction, "So soll" (so shall), reinforces that the Rights Clause stands alone: "[and] so shall the right of the people to keep and bear arms not be infringed/restricted."

So I translate this 1809 G-A translation as:

"[Where]as a well-outfitted militia is necessary for the Security of a free State, so shall the Right of the People to keep and to bear Arms not be restricted.”

The other translations are syntactically/thematically similar

"[Where]as a well-outfitted militia is necessary for the Security of a free State, so shall the Right of the People to keep and to bear Arms not be restricted.”

The other translations are syntactically/thematically similar

This article has been officially accepted by the American Journal of Legal History and moved to copy editing/proofing.

The article also looks at later 19th-century translations, with my findings here:

https://twitter.com/kinney_bc/status/1531082795354816513?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh