In the early hours one July morning, a long column of men, horses, and carts makes an abrupt change of course. They march swiftly through the predawn darkness to make a surprise attack, one which after eleven long years of war will decide the fate of Europe—the Battle of Denain!

The year is 1712 and the War of the Spanish Succession has been raging for over a decade. Things have been going badly for France. Louis XIV’s bid to dominate Europe has stalled, and France itself is now faced with invasion.

After the disasters of Ramillies (1706) and Oudenarde (1708), his northern front has slowly collapsed. The Spanish Netherlands have been lost and the fighting is now in France proper.

The brilliant Marshal Villars managed to check the Austrian, English, and Dutch at Malplaquet in 1709, a costly pyrrhic victory for the Allies, but over the next few years they continue to progress.

https://twitter.com/bazaarofwar/status/1466753117194797062

By 1711 the Allies have managed to breach the Ne Plus Ultra line, the final chain of forts and trenches guarding northern France.

In 1712 they besiege Landrecies, the last fortress standing between them and Paris.

In 1712 they besiege Landrecies, the last fortress standing between them and Paris.

The mood at Versailles is grim. Things are so desperate that the aging Louis vows to march out at the head of his nobles and oppose the invaders in the field if Landrecies should fall.

Both sides are exhausted, however, and the war is especially unpopular in Britain. The great general Marlborough, victor of Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, and Malplaquet, has many political enemies at home who manage to have him recalled early in 1712.

https://twitter.com/bazaarofwar/status/1466753635430420488

This is a sign that Britain is wavering—a problem for the Allies, as she is their principal financial backer. Louis has stubbornly held out against an unfavorable peace despite all setbacks, so the race is on to win a crushing military victory.

The Allied army is commanded by Eugene of Savoy, who shared Marlborough’s successes at Blenheim, Oudenarde, and Malplaquet. He is a daring and aggressive general, skilled at using bold maneuvers to stymy his adversaries.

https://twitter.com/bazaarofwar/status/1466753433319452678

In mid-July he takes Le Quesnoy and a few days later opens up the siege trenches around Landrecies.

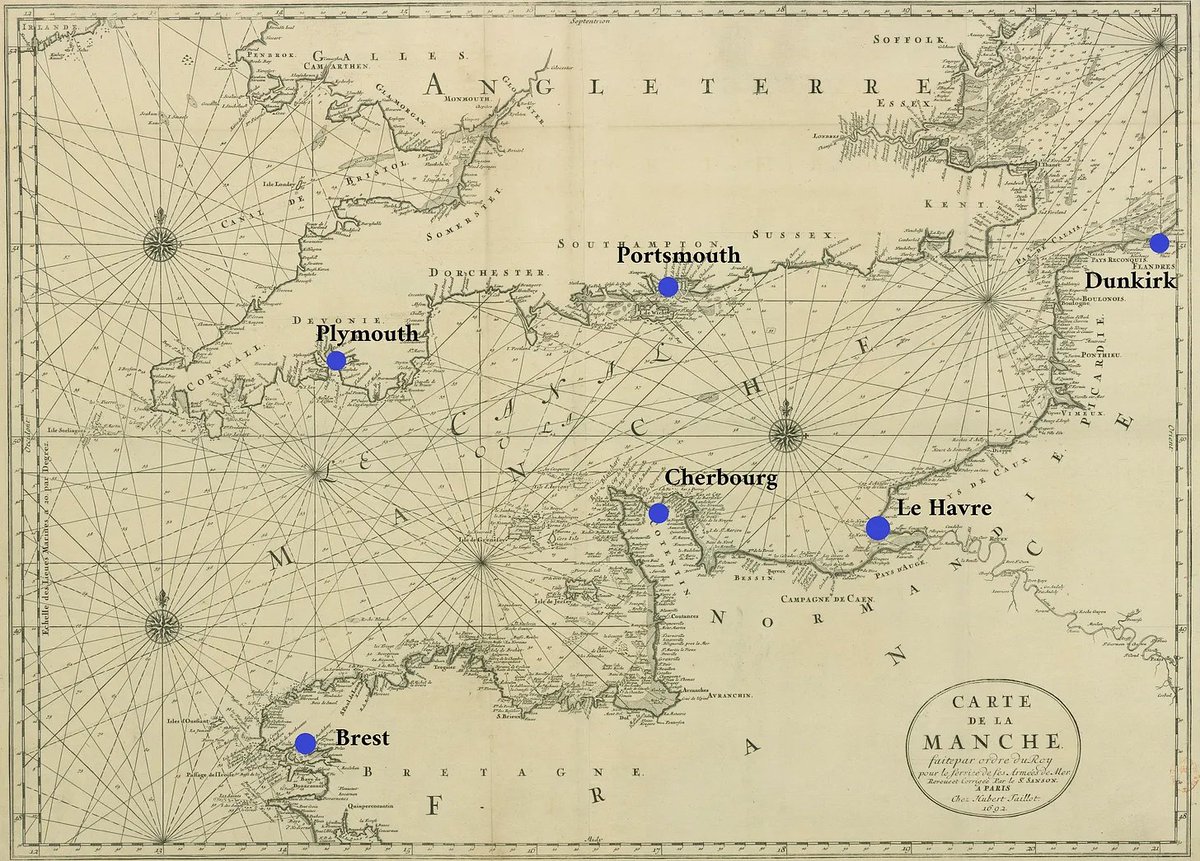

This is a complex operation, with supply lines running some 30 km to the Scheldt at Denain, passing between the unconquered fortresses of Valenciennes and Cambrai.

This is a complex operation, with supply lines running some 30 km to the Scheldt at Denain, passing between the unconquered fortresses of Valenciennes and Cambrai.

From there it is another 15 km to Marchiennes, the supply magazine on the Scarpe.

Eugene pleads with the Dutch (who run the logistics) to move this to Le Quesnoy, but they refuse; he builds a palisaded road between Marchiennes and Denain to protect his supply convoys.

Eugene pleads with the Dutch (who run the logistics) to move this to Le Quesnoy, but they refuse; he builds a palisaded road between Marchiennes and Denain to protect his supply convoys.

This also requires leaving a large cavalry to screen Valenciennes and the length of the lines to Landrecies.

Still, their position is strong: protected by a pair of tributary streams to the west and earthworks in the gap between the streams and the Sambre.

Still, their position is strong: protected by a pair of tributary streams to the west and earthworks in the gap between the streams and the Sambre.

There is one other problem. During the siege of Le Quesnoy, the commander of the British contingent Ormonde is ordered to withdraw. He does so reluctantly and takes the English troops with him, but most of the Hanoverians and German mercenaries remain behind.

Nevertheless, the Allies hold a strong numerical advantage over the French army Villars is massing between Arras and Cambrai. Their rear is protected by fortresses at the major river crossings, their siege camp at Landrecies is well protected by the covering army and the Sambre.

Villars’ intentions are clear. The French position is desperate and he’s running out of time to relieve Landrecies.

On 19 July the army passes the Scheldt by Cambrai. The following day it advances across the plain to the tributary stream.

On 19 July the army passes the Scheldt by Cambrai. The following day it advances across the plain to the tributary stream.

French hussars screen their left, keeping an eye on the streams and Allied-controlled Bouchain. In the next few days, pioneers put up bridges across the Sambre and pre-position fascines to fill the Allies’ trenches.

Everything is staged for a decisive battle.

Everything is staged for a decisive battle.

The two opposing commanders, Villars and Eugene, are friends and rivals. They knew each other during the Great Turkish War, when both fought at the Second Battle of Mohács in 1687.

25 years later they’re two of Europe's most brilliant generals, facing off in a final showdown.

25 years later they’re two of Europe's most brilliant generals, facing off in a final showdown.

On the evening of the 23rd, Villars gives orders for an attack the following day. The army will cross the Sambre before dawn and assault the Allies’ siege camp. The men are excited as they advance that evening to the river.

But secretly, Villars issues another set of orders…

But secretly, Villars issues another set of orders…

Just after dark, 30 battalions and 30 squadrons from the left wing march north to the Scheldt with pontoon bridges.

When the rest of the army awakes the following morning, they are surprised to learn there’s been a change of plans!

When the rest of the army awakes the following morning, they are surprised to learn there’s been a change of plans!

The army retraces its steps in the predawn hours then turns north to make a rapid 25-km march to Neuville-sur-Escaut, a narrow point on the Scheldt where the bridges have been erected. Not long after daybreak the French begin crossing in several columns.

By this point the Allies have been alerted.

Eugene, who has positioned himself midway between the Scheldt and the Sambre, rushes north with some dragoons and infantry to reinforce the Dutch detachment at Denain.

Eugene, who has positioned himself midway between the Scheldt and the Sambre, rushes north with some dragoons and infantry to reinforce the Dutch detachment at Denain.

Denain itself is only a small village, but the Allies have turned it into a large camp surrounded by ditches and palisades, guarded by about 10,000 Dutch.

By one o'clock in the afternoon, the French are in position and begin their assault on the entrenchments.

By one o'clock in the afternoon, the French are in position and begin their assault on the entrenchments.

Some 10k defenders are faced by 24k assaulting infantry plus guns—outnumbered, but not hopelessly so given their entrenchments.

But the surprise and ferocity of the French attack cause them to flee across the Scheldt; the bridges collapse under their weight, drowning many.

But the surprise and ferocity of the French attack cause them to flee across the Scheldt; the bridges collapse under their weight, drowning many.

The collapse of the bridges means that Eugene cannot come to their aid with the main army.

He tries to cross the one remaining bridge east of Denain, but the garrison of Valenciennes sorties out to block their passage, and this bridge is eventually destroyed.

He tries to cross the one remaining bridge east of Denain, but the garrison of Valenciennes sorties out to block their passage, and this bridge is eventually destroyed.

4000 Allied troops are captured and a couple thousand killed or drowned—not a terrible loss.

What is much bigger is that Eugene is cut off from his supplies. He is in no position either to attack or continue the siege, and has to flee northeast to avoid being destroyed.

What is much bigger is that Eugene is cut off from his supplies. He is in no position either to attack or continue the siege, and has to flee northeast to avoid being destroyed.

Villars takes advantage of the breathing space to capture the magazine at Marchiennes, then rapidly rolls up other nearby fortresses—Douai, Bouchain, and Le Quesnoy.

In a matter of weeks, he undoes years of Allied progress. France is saved.

In a matter of weeks, he undoes years of Allied progress. France is saved.

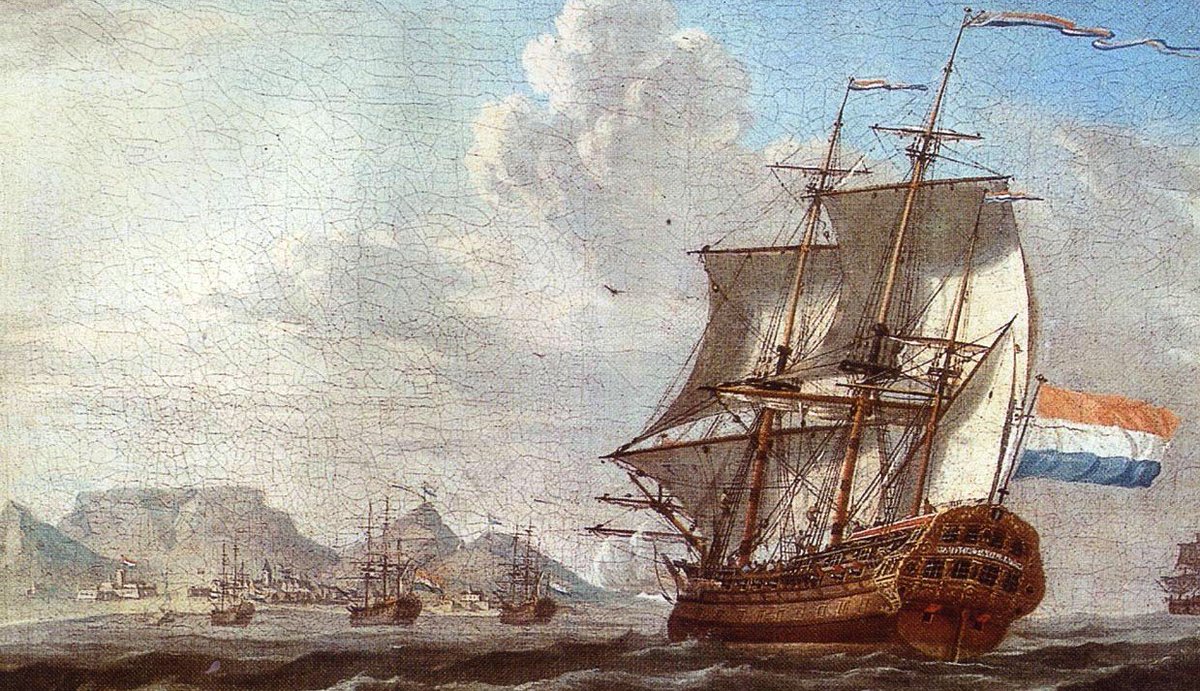

The Dutch and British make peace with France the following year. Villars and Eugene square off again in the Rhineland, but without outside support, Austria cannot field a very large army, and the two old friends negotiate a settlement on behalf of their monarchs.

The War of the Spanish Succession is the last of the great wars of Louis XIV. It ends France’s ambitions as a hegemonic power, but the Battle of Denain also ensures that Louis’ grandson remains on the Spanish throne and that France preserves some territorial gains.

Denain is interesting because it shows the importance of the operational level of war. Unseating an enemy position by rendering its position untenable is far more efficient—and often far more effective—than defeating it in a large set-piece battle.

It also shows how even overwhelming victories can still be extremely close. Eugene had foreseen the possible danger to Denain and positioned himself between it and Landrecies. He later claimed that had the Dutch held out another half hour, he could have salvaged the situation.

Above all, it shows how much more sophisticated the wars of Louis XIV were than is commonly understood. They were criminally understudied by 20th-century theorists, resulting in a very primitive model of the evolution of warfare.

More on this in the future…

More on this in the future…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh