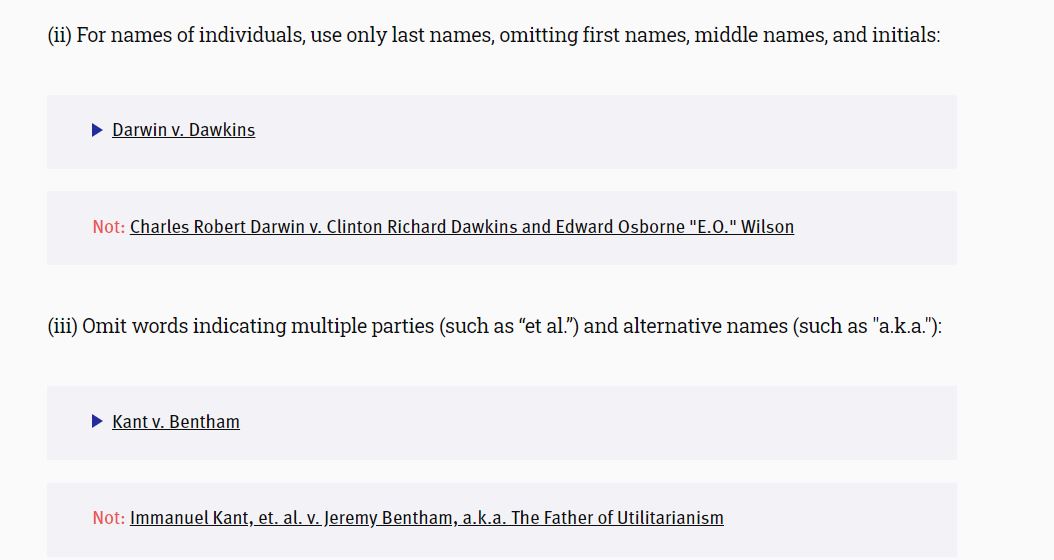

A federal district court in North Carolina has ruled that 24 is not "double" 12. Ugh.

Folks, if your court rule says "double spaced," that rule should *not* come with the implied qualifier: "as defined by the people who design Microsoft Word."

But anyway, here goes... 1/

Folks, if your court rule says "double spaced," that rule should *not* come with the implied qualifier: "as defined by the people who design Microsoft Word."

But anyway, here goes... 1/

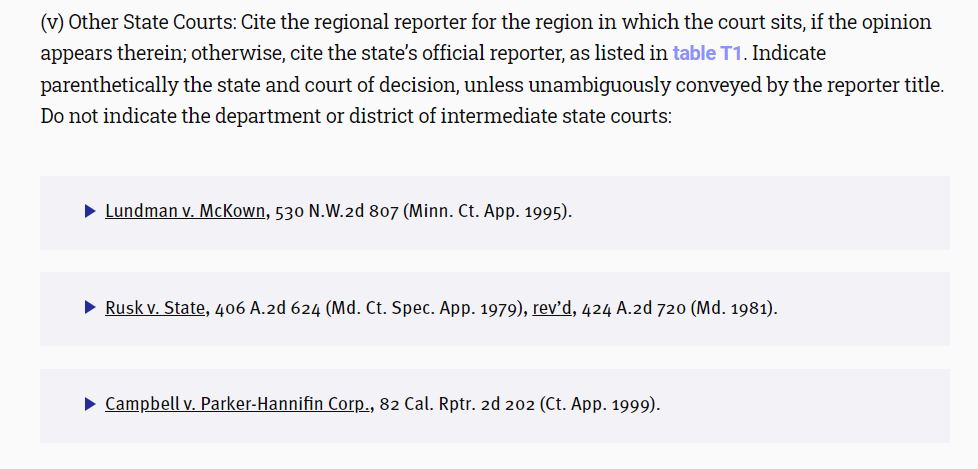

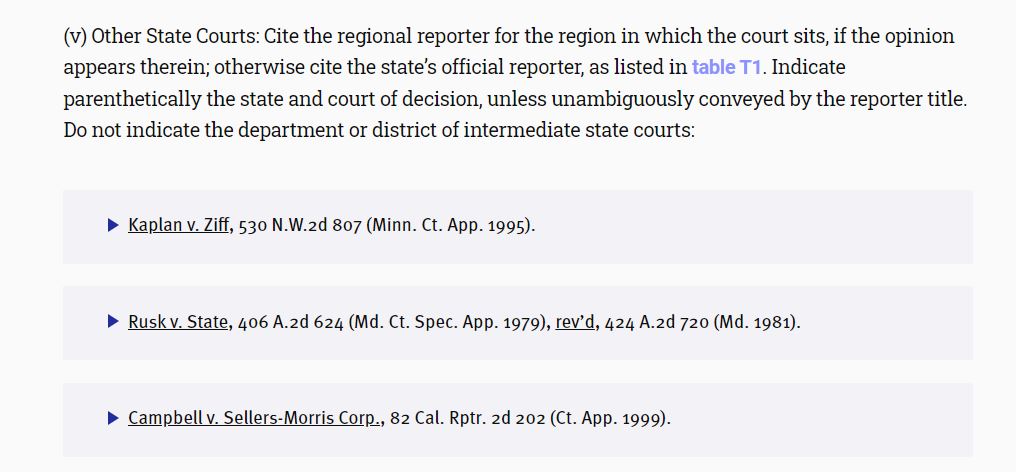

The Court reasons that because most word processing programs have a standard setting for "double" that might not be actually 2x the font size, the Court's rules incorporate that standard. (Note: Does every word processing program use the same spacing for that setting?) 2/

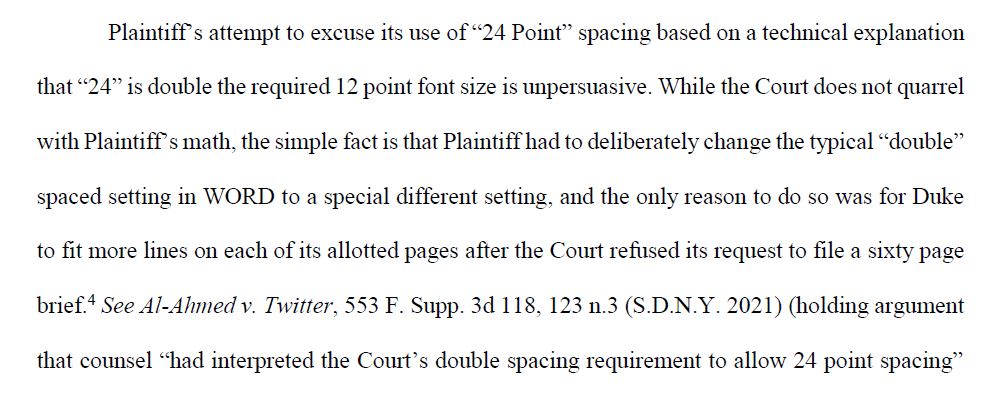

Ah yes, the "technical explanation" that 24 is actually double 12. It is, indeed, hard to quarrel with that! 3/

. . . 4/

Also, it doesn't seem sinister to me that previous filings used "double" spacing instead of 24-point spacing. If a court has a ten-page limit, and I submit a bunch of nine-page briefs, I can still later submit a ten-page brief if I have more to say. Right? 5/

And yes, many other courts have held that "double" means Microsoft's definition of double, which is more than double. At this point, I guess lawyers should be on notice. I suppose we should advise against *actual* double spacing. But that advice seems... 6/

...wrong: typographyforlawyers.com/line-spacing.h…

Oh well.

Here's the full order: ziffblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/order-…

#fonts #legalwriting #judicialmath

/fin

Oh well.

Here's the full order: ziffblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/order-…

#fonts #legalwriting #judicialmath

/fin

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh