Holy crap: Although it was barely mentioned in the briefing, the CA9 just held in a single sentence, in a precedential opinion, that Internet content preservation isn't a seizure. And TOS eliminate all Internet privacy. Here's the entire discussion. Lordy.

cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opin…

cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opin…

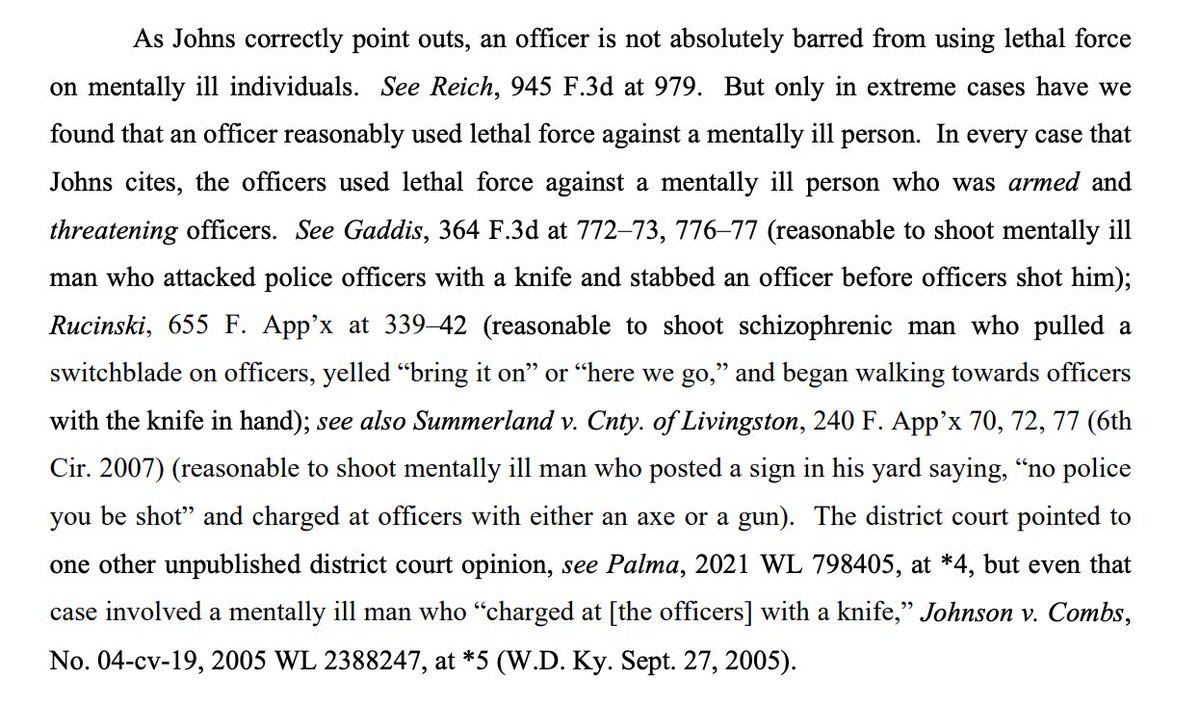

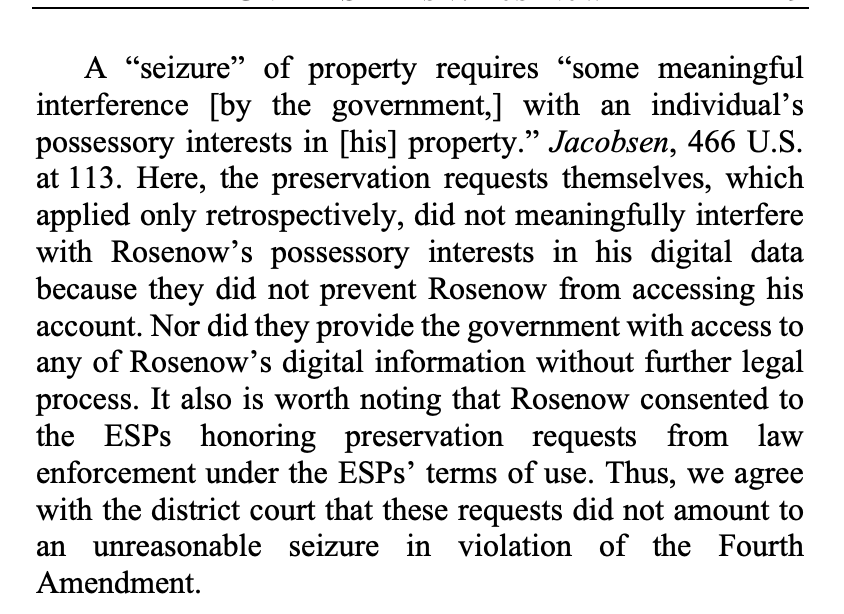

Literally, that's it. No analysis. No citing anything. No discussion. And just a single sentence. So now, under 9th Circuit law, the government is free to order everyone's entire Internet account copied and held for it--with no cause at all. At any time, for no reason.

This is basically the nightmare: There's a major issue, but it's raised in passing by counsel that has no idea what it has; and then federal court of appeals has no idea what it has; and in passing the court decides a major issue, perhaps having no idea of its importance.

And then in the very next section, the Court goes into glorious detail rejecting the entirely silly argument that basic subscriber information is protected under the 4th Amendment. *That's* what you spend the time on?

I know the 9th Circuit has some doozies, but this one, sheesh.

BTW, this was me last week, wondering why that case hadn't come down yet -- wondering if perhaps the court might say something about preservation.

https://twitter.com/OrinKerr/status/1517646922558828544

To be clear, if the court had actually taken this on, and showed some sign it understood the arguments, and concluded that yes, the government is always free to copy your private data b/c you still have your own copy, that would one thing. Stunning & jawdropping, but so it goes.

But this has the feel of a case where the defendant raised 20 issues, including a bunch in passing, and no one understood, hey wait, this one raised in passing is 100x more far-reaching than anything else in the case. So they just blew it off without even thinking about it.

This and then some.

https://twitter.com/pwnallthethings/status/1519371484342366208

Some may not think limits on Internet preservation are needed. And if you think that, that's fine. But note that the reasoning isn't limited to preservation: This just became the most important sentence in federal law on whether copying data is a seizure, holding it isn't.

Given that the CA2 went en banc in Ganias, which had held copying *is* a seizure (an issue the en banc court didn't reach), this is now the only federal appellate precedent on that foundational question. And it's a sentence!

And then there's the additional holding/suggestion that TOS amount to consent to eliminate all Internet privacy rights. I mean, maybe don't try to take on the most contentious issues, with the most extreme implications, in passing, without briefing, in a precedential opinion?

Also, my apologies if this thread is harsh. It's just hard, after having spent so much time, two articles, & a draft brief on this, to see it dismissed as an afterthought in circumstances that have remarkably far-reaching and troubling implications the court didn't seem to see.

(BTW, I feel extra double guilty criticizing this given that the court cited an article of mine elsewhere for a different issue. A little bit of an uncomfortable position to be in, but it seems better not to have that change my reaction.)

Looking a bit more closely, I wonder if there's an easy way out of this. If you read Rosenow's opening merits brief, it's not at all clear he raised the issue; he addressed it instead in the reply brief. Under CA9 precedent, wasn't the issue waived?

Here's the passage from the opening brief. The question is, did this sufficiently raise the question of whether preservation of Internet contents under 18 U.S.C. 2703(f) was an unreasonable seizure?

To be clear, I'm not arguing that it was waived in this opinion. It wasn't. I'm wondering if the court should have treated it as waived, which might be relevant to future proceedings.

The standard under CA9 precedent is whether the appellant "specifically and distinctly argue[d] the issue in his or her opening brief." United States v. Kama, 394 F.3d 1236, 1238 (9th Cir. 2005). I don't see how that was satisfied here.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh