Lying awake at night, I read this tweet by @TonyHWindsor, encouraging someone to “learn what our Constitution says and how Governments are formed”. As a citizen of Australia, I suffered sudden shame of never having done that myself. So I did and here's an #auspolVote2022 thread🧵

https://twitter.com/TonyHWindsor/status/1520273822137880576

The context here is the upcoming Australian election and the participation of high-profile Independent candidates, not associated with a political party. That’s not new; there were Independents elected to the House of Reps in the first parliament of 1901. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1901_Aust…

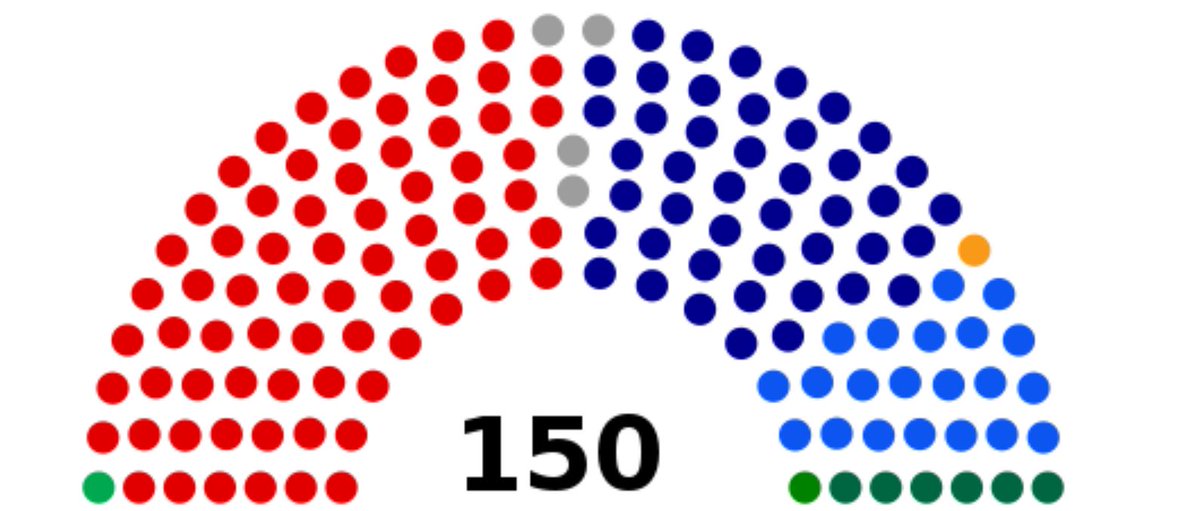

But this year, some people are concerned with the prospect that no major political party (or established coalition of parties) may have enough members elected to form a majority in the House of Reps, leading to ‘minority government’ or a ‘hung parliament’. smh.com.au/politics/feder…

Minority government is unusual in Australia, but has occurred a couple of times. Once in 1940 when the Coalition led by Robert Menzies formed government with only 36 seats out of 74, and again in 2010 when the ALP formed government led by Julia Gillard with 72 of 150 seats.

So what does the Constitution of Australia prescribe in this circumstance? Here’s what I found: In the context of the House of Representatives, the Constitution makes no mention of ‘political parties’, nor does it specifically mention the office of “prime minister”.

The first thing to understand is that the ultimate ‘boss’ in the Australian parliament is not the prime minister, but the Queen of Australia, who reigns over the Monarchy of Australia as Head of State. That’s currently Elizabeth II, better known as Queen of the United Kingdom.

The Australian Constitution creates the role of the Governor-General, appointed by the Queen to be her representative in the Commonwealth and to exercise such powers and functions of the Queen as she may be pleased to assign to “him”.

The Constitution also creates “The Senate”, with senators for each State elected by the people of the State voting as one electorate. The Senate has the power to pass, amend or reject many types of proposed laws, which are passed up to it from the House of Representatives.

So the Constitution also creates the “House of Representatives”, with members elected from roughly equal-population ‘electoral divisions’. This is where most laws are first drafted and -once agreed by majority vote- are passed up to the Senate for its approval.

Once a proposed law is passed by both Houses, it is then passed to the Governor General, who can provide approval [“assent”] in the Queen’s name, reject it, or pass it on to the Queen “for the Queen’s pleasure”. The Queen may also disallow laws that had received the GG’s assent.

While there is no “prime minister” referred to in the Constitution, there are “Ministers of the State”, appointed by the Governor-General (and can be sacked by the GG) to manage the “departments” of State as the government may establish. Ministers can come from either house.

All Ministers of State, become members of the “Federal Executive Council" (FEC) to advise the GG in the government of the Commonwealth. While it’s not explicit, the GG is bound by convention to follow the advice of the FEC on almost all occasions. aph.gov.au/About_Parliame…

So, according to the Constitution, any senator or Member of the House of Reps can become a Minister (including the PM), as long as the GG (and ultimately the Queen) agrees. And Ministers, as members of the FEC get to advise the GG on most aspects of government from thereon. 😐

Ahh, but then there are things called “conventions”. They don’t appear in the Constitution, but are established and generally accepted rules of practice. An official version of the Australian Constitution includes overview notes by the Australian Government Solicitor which state:

Circumstances in which there is no explicit requirement in the Constitution and no generally agreed convention can lead to a constitutional crisis, such as that which occurred in 1975 with dismissal of Gough Whitlam as Prime Minister:

So what does all this mean for this 2022 election? If any political party or coalition of parties has a majority of seats in the House of Reps, they will ask the GG to appoint their leader as PM and other members as Ministers and members of the FEC. The GG will agree to do so.

If no party has a majority, they'll need to convince the GG to appoint a PM & ministers. To do that, they will need to demonstrate that they have support of the majority. This will give minor parties and Independents the opportunity to support a party that needs extra numbers.

That’s a very powerful position to be in (known as ‘having the balance of power’), since support can be bargained for. Potential supporters could request many things in return, such particular laws to be supported or even to be made a Minister.

The ongoing functioning of the parliament would continue to work in much the same way. Each new bill would require majority support to pass through each house of parliament, but the individuals comprising that majority may not be the same each time.

In my opinion, a parliament with a minority government and a large crossbench of minor parties and Independents can provide very robust government. Yes, there’ll be lots of deal-making, but all bills will be exposed to robust debate.

Should Independents be expected to indicate -prior to the election- which major party they would support? I think its perfectly fair for them to state that they should wait and see the elected composition of the parliament and then see who wants to talk.

https://twitter.com/StevePriceMedia/status/1519784994054762496?s=20&t=y7lGxDo6Pm8FPOXW5TLUVg

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh