In describing his version of Colossus, Marc Silvestri speaks to the character’s capacity for visceral visual impact, but also of the (less-considered) emotional relationship between artist and character, something that can impact (or even define) the resulting imagery. #xmen 1/6

For Silvestri, that relationship is defined by “glee,” something that might be counter-intuitive for an artist known for dark characters and kinetic violence, but his sense of joy is clearly the focus when he describes Colossus in an interview with Marvel Age: 2/6

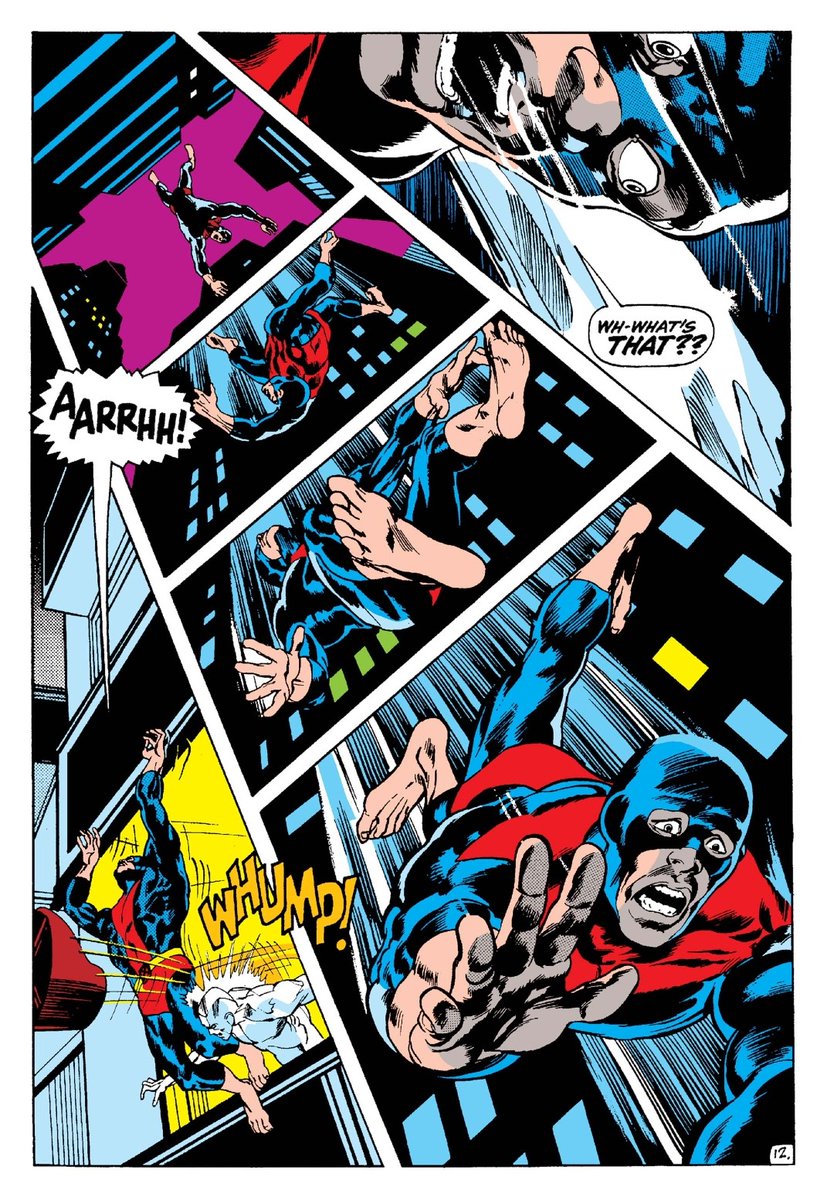

“Colossus is always a lot of fun. Any time you have to draw a big bruiser like that, you know you’re going to have a good time. There’s a lot of broad action with him because of his strength and size.” 3/6

“You can have people flying all over the place, crashing through walls and windows, and that’s always a lot of fun. When I have to do a scene with Colossus, I’m in a good mood that day.” 4/6

“His armored body is also visually striking. It works well in a color comic to have this chrome-plated giant running around with these giant fists and pounding the bad guys. It’ a lot of fun.” 5/6

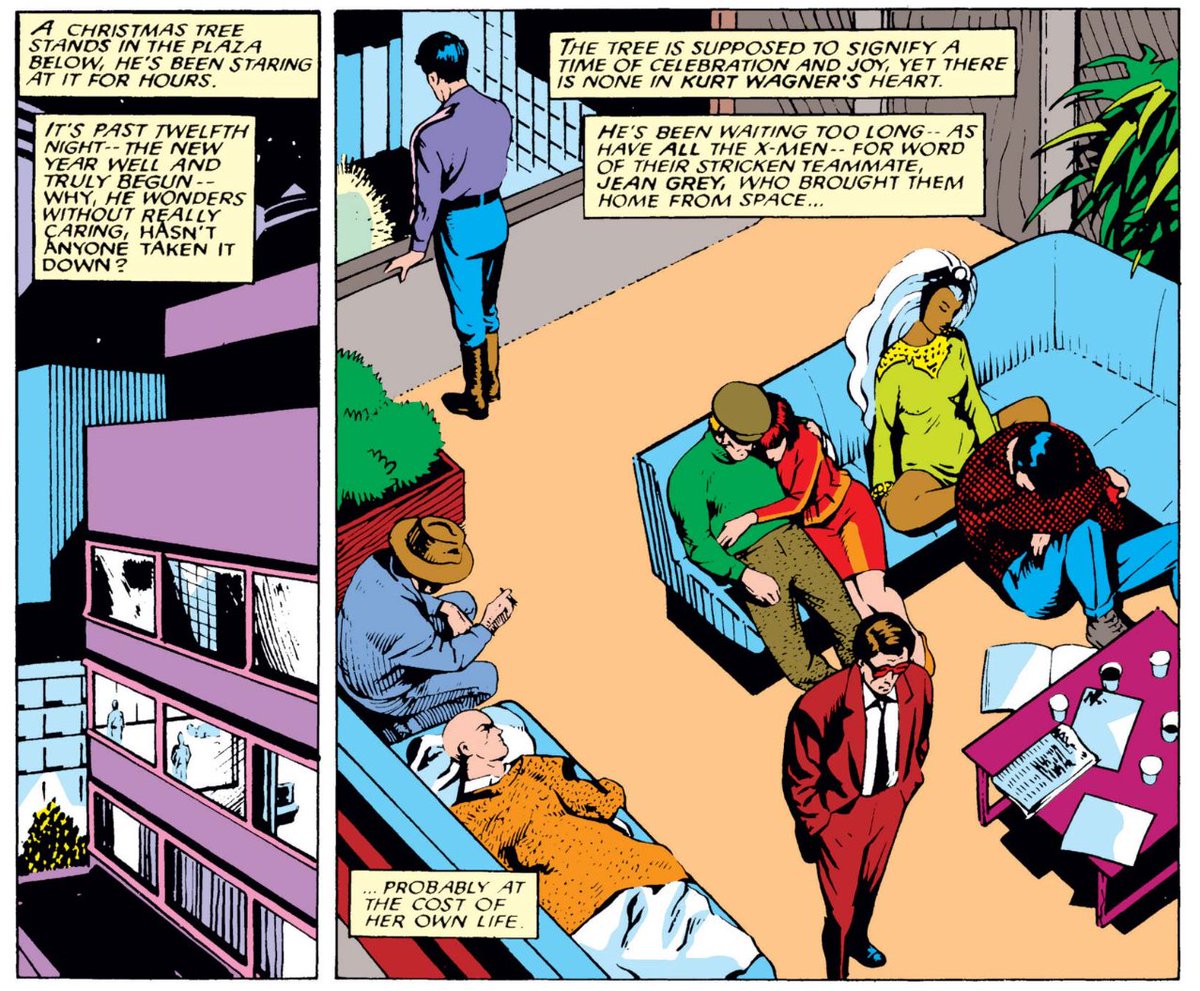

Even in comics scholarship, we speak constantly about the emotional relationship between writer/character but the relationship between artist/character is just as pivotal, and considering that Silvestri/Piotr is defined by glee adds new layers to the art. 6/6

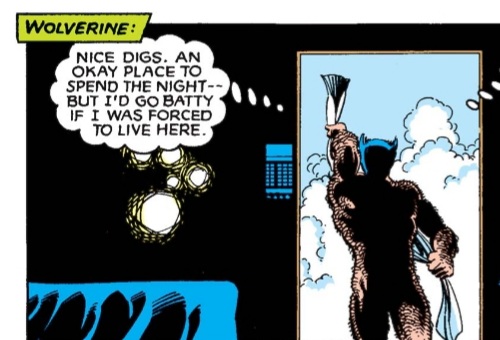

Just as an aside that I’m cheating by putting into this thread, I’m wondering if this connects at all to something we disproved last year with content analysis: the long-held belief that Byrne drew Wolverine more than anyone.

My thought, which I can’t prove, is just that it might not be volume of illustration that put said idea into people, so much as care of composition or any of the infinite subtleties by which an illustrator’s preference for a character can emerge in their figure drawing? I dunno.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh