Government departments (like @USDA & @DHSCgovuk) frequently publish dietary guidelines. But looking at hunter-gatherers & forager-farmers, I'm struck by how many violate Western guidelines yet have healthier hearts & much less chronic illness.

Here are 3 well-studied examples:

Here are 3 well-studied examples:

1. Kitavans of Trobriand Islands (Papua New Guinea)

In 1990, Staffan Lindeberg spent several months w/ the Kitavans, observing their diet, physical activity, & daily habits. He also measured a slew of health & physiological variable for ~170 adults.

In 1990, Staffan Lindeberg spent several months w/ the Kitavans, observing their diet, physical activity, & daily habits. He also measured a slew of health & physiological variable for ~170 adults.

Lindeberg found that 70% of the Kitavan's calories came from carbs (e.g., fruits, yams, sweet potato, taro) & ~17% from saturated fat (coconut oil), both in excess of @USDA guidelines. Yet he observed no diabetes & "cardiovascular disease was virtually nonexistent”.

2. Tsimane of Bolivian Amazon

Since 2002, @MGurven, Hilly Kaplan, @j_stieglitz & others have studied the diet, health, behavior, & life history of 1000s of Amazonian forager-farmers. This is (I believe) the most detailed study of health in a small-scale non-industrial society.

Since 2002, @MGurven, Hilly Kaplan, @j_stieglitz & others have studied the diet, health, behavior, & life history of 1000s of Amazonian forager-farmers. This is (I believe) the most detailed study of health in a small-scale non-industrial society.

Like the Kitavans, the Tsimane eat too many carbs by @USDA standards: ~65% of calories are from starchy cultigens (e.g., rice, manioc, plantains) + more come from other fruit. They also consume ~300 mg calcium/day — far less than typical Western recommendations of >1000 mg/day.

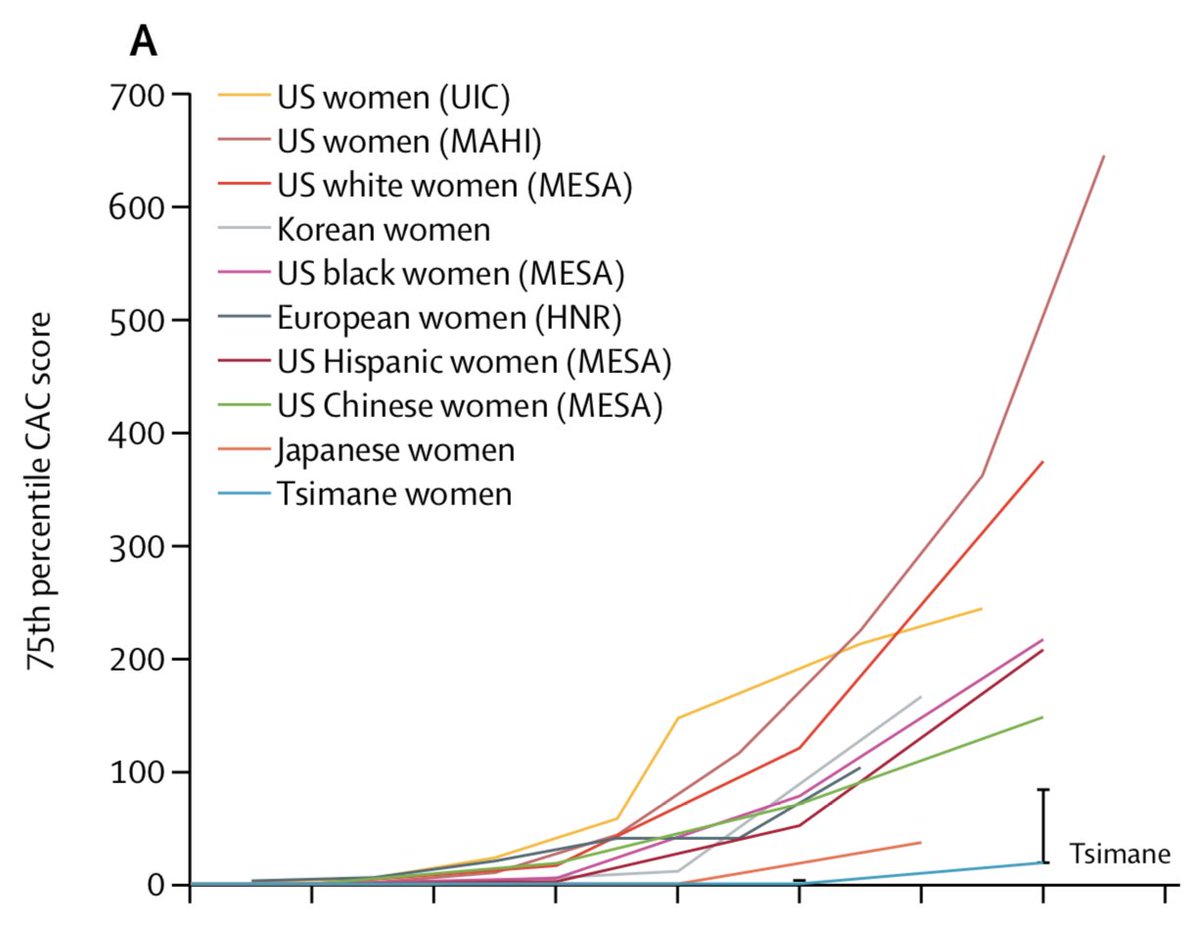

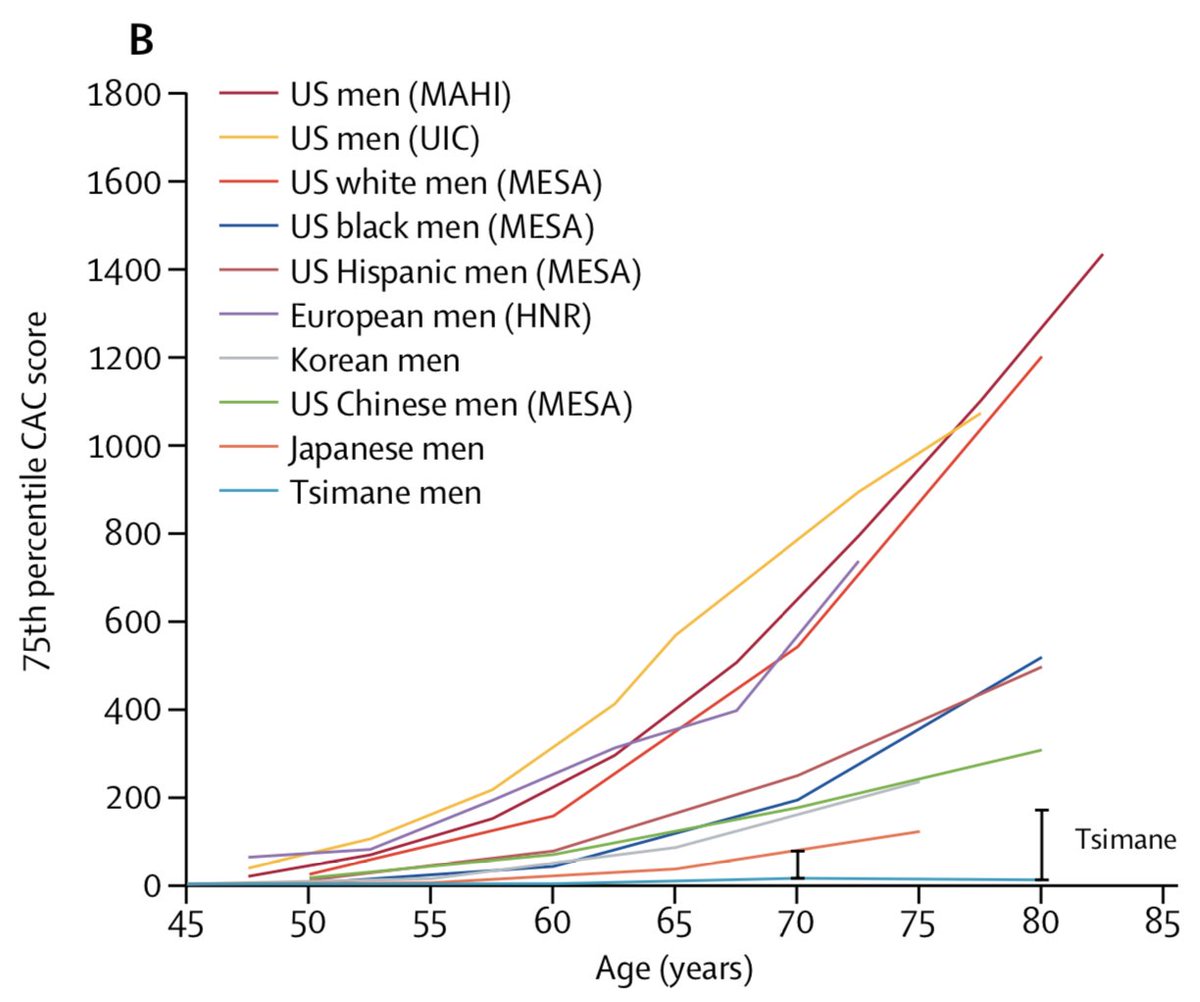

Despite the carbs & very low calcium, the Tsimane are medical marvels compared to Westerners. They have hardly any fatty liver disease, brains that atrophy much more slowly with age, & the lowest levels of coronary artery disease ever recorded in a population (see plots).

3. Hadza of Tanzania

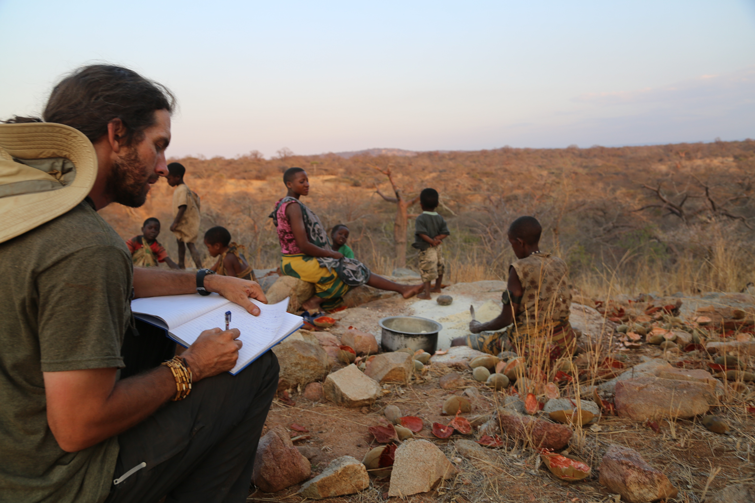

For years, researchers like Frank Marlowe, @briwood1 (pictured), @Berbesque, @HermanPontzer, & others have conducted detailed studies of Hadza hunter-gatherers, collecting valuable data on health, diet, & behavior.

For years, researchers like Frank Marlowe, @briwood1 (pictured), @Berbesque, @HermanPontzer, & others have conducted detailed studies of Hadza hunter-gatherers, collecting valuable data on health, diet, & behavior.

Most striking about the Hadza diet is the quantity of simple sugars in the form of honey. According to @Berbesque's data, >60% of Hadza calories come from honey some months. On average, the Hadza seem to get ~400 calories from honey/day — vastly exceeding @USDA guidelines.

Despite all the honey, of 192 Hadza people studied, only 2 (barely) qualified as overweight and one (barely) qualified as obese. There is also no evidence of type II diabetes. Of 20 people checked, none had fasting blood glucose levels >85 mg/dL (diabetes is >125 mg/dL).

Why the lack of cardiac & metabolic disease among foragers & forager-farmers? There are many possibilities: More fiber, less salt, more pathogens, more activity. But honestly, we don’t know. We still struggle to understand why industrialized lifestyles carry such health risks.

A final note: These examples aren't cherrypicked. Rather, these are the subsistence populations whose diets and health have been, to my knowledge, best studied. I am sure that many peoples deviated further from Western guidelines yet were still mostly free of chronic disease.

Most of the info in this thread comes from these reviews:

- onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.11…

- annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.114…

- researchgate.net/profile/Staffa…

The Tsimane plots are from here: sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

- onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.11…

- annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.114…

- researchgate.net/profile/Staffa…

The Tsimane plots are from here: sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh