An updated version of my map on pre-Islamic Arabia (c. 600 CE), adding more details and also incorporating some of the helpful feedback that I received.

# 1: Most obviously, I added the Roman Empire in the Levant and Egypt, their client Kingdom of Ḡassān in NW Arabia, and their ally Aksumite Kingdom in the Horn of Africa, based on some existing maps.

# 2: I speculatively included Dūmat al-Jandal in the zone of Ḡassān, since there is a report that it was convened by the Ḡassān.

# 3: I added Persian client tribes or tribal kingdoms across Arabia, including Laḵm, the Banū Tamīm, the Banū Ḥanīfah, the ʾAzd of Oman, and Ḥimyar.

# 4: I removed Ḍubā [modern Dubai] and added Dibbā in Oman.

# 5: I disambiguated Najd and al-Yamāmah, since some sources apparently claim that they are separate regions. This is clearly a contentious issue, since there is a famous Sunni hadith that claims that “the horn of Satan will emerge from Najd”.

This hadith is cited by some Sunnis to attack Wahhabis, since the Wahhabi movement came out of al-Yamāmah, which is usually considered part of Najd. Against this, Wahhabis are obviously very motivated to deny that al-Yamāmah was in fact part of Najd!

I sidestepped this debate through ambiguity: since Najd definitely includes the region west of al-Yamāmah, I placed “Najd” there; and although I included a separate “al-Yamāmah” designator, this could be interpreted on the map either as a sub-region of Najd or as its own region.

# 6: The Sasanids reportedly had mining colonies (including a Zoroastrian fire temple) in Najd, especially at a place called “Šamām”. No one seems to know where this was, so I initially indicated the Sasanid presence with a dark green patch around the capital of al-Yamāmah.

I have since moved this patch westwards, to the area around al-Dawādimī, where there were mines that supplied silver to the Sasanids. However, I do not actually know if al-Dawādimī was one of the mines where the Persians *themselves* were present, so this is speculative.

# 7: I slightly expanded Tihāmah (given as part of the Persian zone of influence) to closely reflect the actual physical coastal plains.

# 8: I extended the Persian zone of influence in northern Yemen so that it was contiguous with their Najd zone, since they reportedly controlled an overland route from Yemen through Najd to Iraq.

However, this is a bit speculative: I have not been able to verify whether the Sasanids controlled Najrān.

# 9: I removed “ʿAsīr” from the map, since this is the name for a modern region; the older sources just seem to regard that area as simply the northern part of Yeman.

# 10: I decided to omit plausible but unevidenced Persian areas of influence in the Hijaz and Hadramawt (previously indicated by stripes), since the map was becoming crowded, and since it was extremely speculative.

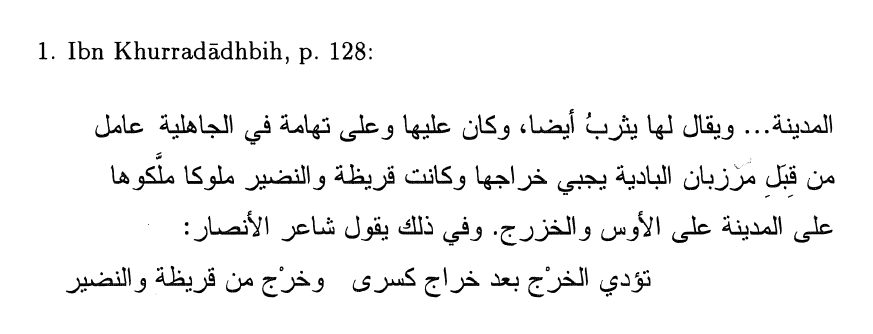

Finally, something I will have to figure out is the specific timeframe. Crone, MT, pp. 49-50, n. 169, argues that if there was a Sasanid governor over Madinah and Tihāmah, it most likely coincided with the Persian invasion and occupation of the Levant (c. 613-630 CE).

However, by that time, the Sasanids had removed the Laḵm and directly annexed their territory. Ergo, the map cannot show both the Laḵm *and* Persian control over Madinah and Tihāmah.

Moreover, if it shows Persian control over Madinah and Tihāmah, it must *also* show Persian control over the Levant and Egypt, if indeed they were simultaneous!

I will probably have to make two maps: one showing Arabia c. 600, and another showing Arabia c. 620.

I owe thanks to all of the feedback I received, especially from @SaqerKAlNuaimi and @Sltn3mkmklkm

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh