This is what you would learn if you went to university in the 12th century.

Could modern schools and universities learn something from it?

A Thread.

Could modern schools and universities learn something from it?

A Thread.

There was, of course, no single Medieval curriculum.

But there was, undoubtedly, a unified mode of education.

That's what we'll be exploring here.

But there was, undoubtedly, a unified mode of education.

That's what we'll be exploring here.

So if you went to university in the 12th century, this is what you might expect to learn.

Bear in mind that Medieval students often started university at 14 years of age.

Bear in mind that Medieval students often started university at 14 years of age.

The standard course of study was six years.

First was the Bachelor of Arts, awarded after three years, which taught the Trivium.

And the Master of Arts, awarded after six, which taught the Quadrivium.

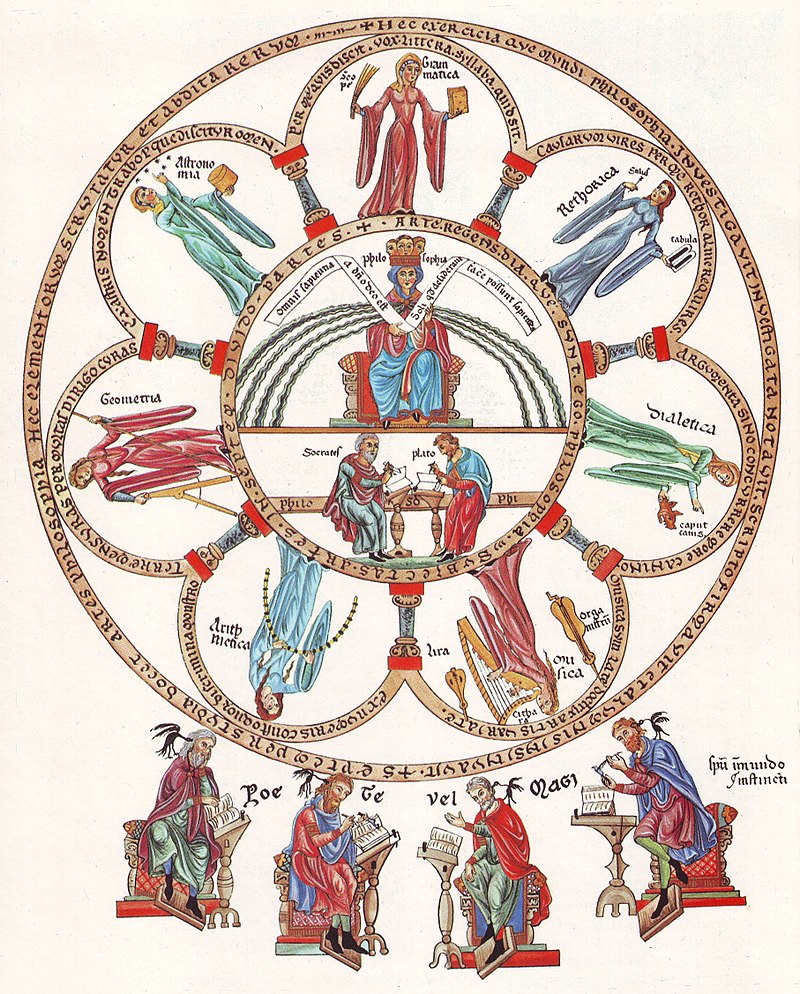

Together they formed the Seven Liberal Arts.

First was the Bachelor of Arts, awarded after three years, which taught the Trivium.

And the Master of Arts, awarded after six, which taught the Quadrivium.

Together they formed the Seven Liberal Arts.

Liberal, coming from the Latin word Liber (meaning free), and Arts from Ars (meaning art or practice).

So it was about free practice. Or, rather, free thinking.

On to the curriculum...

So it was about free practice. Or, rather, free thinking.

On to the curriculum...

Trivium

This was the first course of study. Its three subjects were grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

Grammar is about using language. Logic is about using language to think, or seek truth. And rhetoric is about communicating those thoughts.

You can see how they dovetail.

This was the first course of study. Its three subjects were grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

Grammar is about using language. Logic is about using language to think, or seek truth. And rhetoric is about communicating those thoughts.

You can see how they dovetail.

Quadrivium

This was the second course of study. Its four subjects were arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

This was about numbers.

-Arithmetic (abstract numbers)

-Geometry (numbers in space)

-Music (numbers in time)

-Astronomy (numbers in space & time)

This was the second course of study. Its four subjects were arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

This was about numbers.

-Arithmetic (abstract numbers)

-Geometry (numbers in space)

-Music (numbers in time)

-Astronomy (numbers in space & time)

But how did these studies actually work?

Firstly, they were all conducted in Latin. So students had to be competent both in writing and speaking it.

Latin was the lingua franca of the day, not just ecclesiastically but also academically.

Firstly, they were all conducted in Latin. So students had to be competent both in writing and speaking it.

Latin was the lingua franca of the day, not just ecclesiastically but also academically.

How did pupils study?

Unsurprisingly, it varied. The style of teaching depended on the teacher, especially if there was a particular expert at the university.

You might be scrupulously copying and imitating the styles of great writers, or holding dialectic discussions on truth.

Unsurprisingly, it varied. The style of teaching depended on the teacher, especially if there was a particular expert at the university.

You might be scrupulously copying and imitating the styles of great writers, or holding dialectic discussions on truth.

And here are some of the books you'd expect to study:

-Ars Maior, by Aelius Donatus (Latin grammar)

-Ptolemy's Almagest (cosmology)

-Euclid's Elements (maths)

-Isagoge, by Porphyry (logic)

-Plato's Timaeus (Pythagoreanism)

-Cicero's De Orate (rhetoric)

-Galen's works on medicine

-Ars Maior, by Aelius Donatus (Latin grammar)

-Ptolemy's Almagest (cosmology)

-Euclid's Elements (maths)

-Isagoge, by Porphyry (logic)

-Plato's Timaeus (Pythagoreanism)

-Cicero's De Orate (rhetoric)

-Galen's works on medicine

The Medieval curriculum also taught philosophy, which was divided into four branches each with its own subdivisions:

-theoretical (theology, physics, mathematics)

-practical (political and personal ethics)

-logical (discourse)

-mechanical (navigation, agriculture, medicine)

-theoretical (theology, physics, mathematics)

-practical (political and personal ethics)

-logical (discourse)

-mechanical (navigation, agriculture, medicine)

After receiving the Master of Arts, you would then able to pursue further study in one of the "Higher Faculties."

These were Law, Medicine, or Theology.

Of these, Theology was regarded as the highest and greatest form of study.

These were Law, Medicine, or Theology.

Of these, Theology was regarded as the highest and greatest form of study.

So what stands out?

It's entirely about thinking.

The Medieval curriculum was a coherent system which equipped its students with intellectual mastery.

That was the central goal of the Seven Liberal Arts - not factual knowledge, but the ability to think, speak, and write.

It's entirely about thinking.

The Medieval curriculum was a coherent system which equipped its students with intellectual mastery.

That was the central goal of the Seven Liberal Arts - not factual knowledge, but the ability to think, speak, and write.

And with those fundamentals in place, students could then become lawyers, doctors, or theologians.

There's a purity and harmony to this system.

It works from lower to higher orders of thinking, building towards a singular, all-encompassing goal.

There's a purity and harmony to this system.

It works from lower to higher orders of thinking, building towards a singular, all-encompassing goal.

The aim was to produce rigorously intellectual minds capable of dealing with diverse problems.

But that's not to say there was no repetitive work.

Bernard de Chartres, a 12th century philosopher and tutor, made his students write and re-write Classical texts to learn grammar.

But that's not to say there was no repetitive work.

Bernard de Chartres, a 12th century philosopher and tutor, made his students write and re-write Classical texts to learn grammar.

It's also interesting to note the theological element of this curriculum.

Some people simplify Medieval education as being exclusively religious in nature.

That's not quite correct.

Some people simplify Medieval education as being exclusively religious in nature.

That's not quite correct.

It's broadly true that for a long time the Bible dominated scholarship.

But by the 12th century scholarship had expanded beyond an exclusively monastic or ecclesiastical context.

Quasi-secular universities were founded in Bologna, Oxford, and Paris.

But by the 12th century scholarship had expanded beyond an exclusively monastic or ecclesiastical context.

Quasi-secular universities were founded in Bologna, Oxford, and Paris.

Yet theology didn't disappear.

The Medieval curriculum represents a fascinating marriage between pre-Christian Hellenic philosophy and Christian theological instruction.

For these students, the Seven Liberal Arts (secular study) were preparation for theology (religious study).

The Medieval curriculum represents a fascinating marriage between pre-Christian Hellenic philosophy and Christian theological instruction.

For these students, the Seven Liberal Arts (secular study) were preparation for theology (religious study).

The abstract, secular philosophy of Ancient Greece dovetailed with the moral and religious teaching of Christianity to form, in the end, Humanism.

Two systems of education (the Greek Academy and the Dark Age monasteries) somehow combined into a single, coherent order.

Two systems of education (the Greek Academy and the Dark Age monasteries) somehow combined into a single, coherent order.

So, was Medieval education any good?

The proof is in the pudding.

It produced Humanism, which itself was the founding principle of the Renaissance, and thereafter led to an explosion of artistic, mathematical, architectural, political, economic, and philosophical progress.

The proof is in the pudding.

It produced Humanism, which itself was the founding principle of the Renaissance, and thereafter led to an explosion of artistic, mathematical, architectural, political, economic, and philosophical progress.

The Seven Liberal Arts evolved during the Renaissance to include history and poetry, shifting away from logic and theology.

Dante was a student of this programme, known as the Studia Humanitatis.

And this movement deviated from Latin to vernacular languages such as Italian.

Dante was a student of this programme, known as the Studia Humanitatis.

And this movement deviated from Latin to vernacular languages such as Italian.

But that doesn't undermine the Medieval trivium and quadrivium.

Specific content isn't what matters. Rather, it's the underlying principles and goals of the system.

Studia Humanitatis also represents a coherent vision of scholarship focussed on thinking.

Specific content isn't what matters. Rather, it's the underlying principles and goals of the system.

Studia Humanitatis also represents a coherent vision of scholarship focussed on thinking.

Of course, there is no ideal or universal way of teaching.

For example, many of the Renaissance Masters received little truly 'formal' education, including Da Vinci.

Their artistic talent was recognised early and they learn their craft with other Masters from as young as 12.

For example, many of the Renaissance Masters received little truly 'formal' education, including Da Vinci.

Their artistic talent was recognised early and they learn their craft with other Masters from as young as 12.

Anyway, that's a thread for another day...

As ever, detail has been elided.

But for now I think it is worth trying to imagine how the trivium and quadrivium shaped its students.

And whether modern schools and universities could learn from this approach.

As ever, detail has been elided.

But for now I think it is worth trying to imagine how the trivium and quadrivium shaped its students.

And whether modern schools and universities could learn from this approach.

It's my mission to emulate the spirit of this education.

You can book a 1-1, online tutorial with me right now. And you get to pick the subject ↓

calendly.com/theculturaltut…

(Thank you for all your replies, it is truly humbling. I will endeavour to respond to you all 🙏)

You can book a 1-1, online tutorial with me right now. And you get to pick the subject ↓

calendly.com/theculturaltut…

(Thank you for all your replies, it is truly humbling. I will endeavour to respond to you all 🙏)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh