This week's 🧵

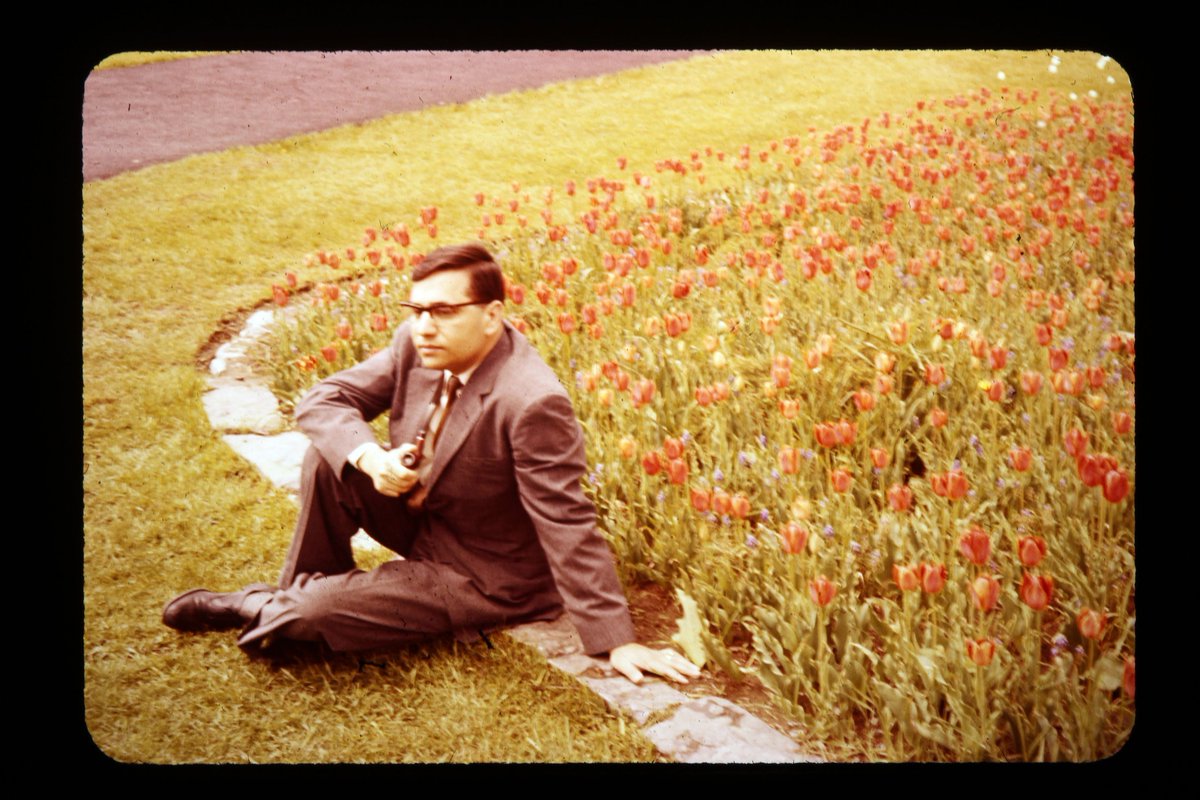

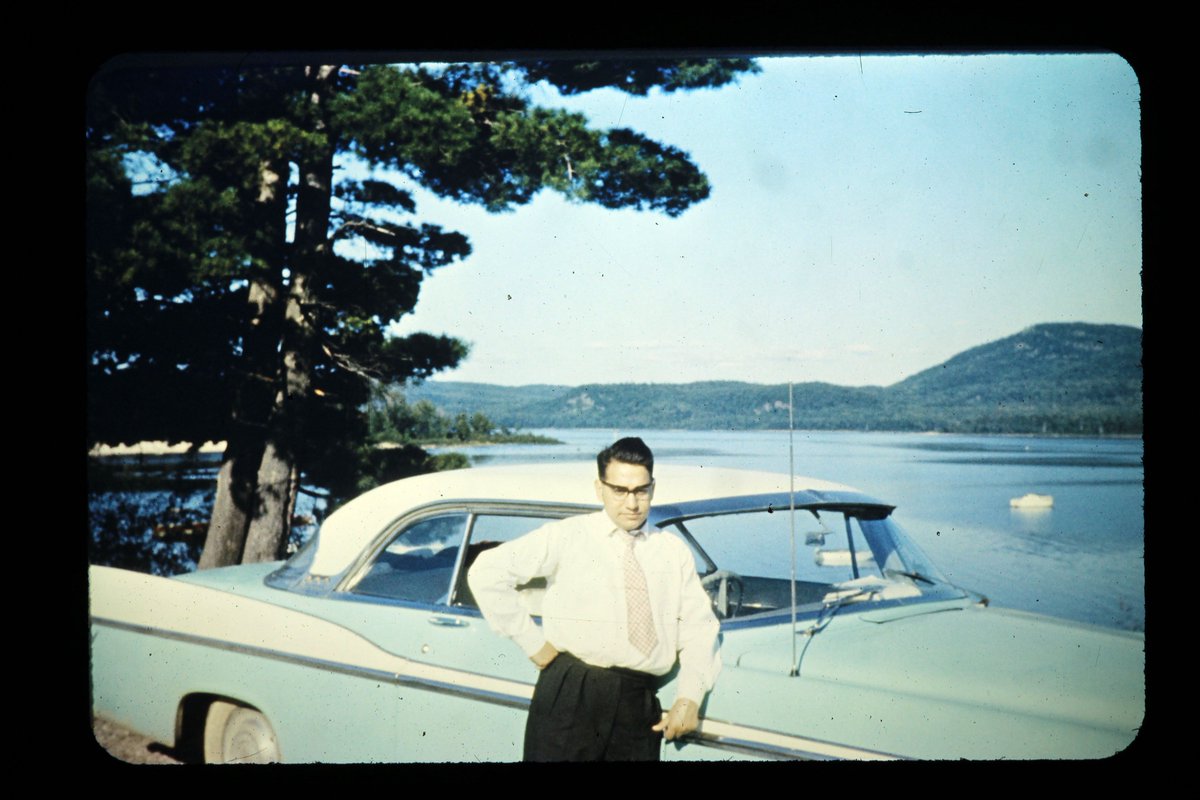

WONDER DRUG: This Punjabi microbiologist dedicated his life to studying a compound. It saved millions of lives—including, for a while, his own.

WONDER DRUG: This Punjabi microbiologist dedicated his life to studying a compound. It saved millions of lives—including, for a while, his own.

Today, rapamycin has saved millions of lives around the world.

The wonder drug is essential for immunosuppression in organ transplant patients and coronary artery stents after balloon angioplasties.

The wonder drug is essential for immunosuppression in organ transplant patients and coronary artery stents after balloon angioplasties.

But for five years in the 80s, the only vial of rapamycin in the world lived in Punjabi microbiologist Surendra Nath Sehgal's freezer, in a glass jar labelled 'NOT FOR EATING'.

In the 70s, Surendra Nath Sehgal—born in Khushab village in undivided Punjab—was a microbiology researcher in Montreal, when his lab received soil samples from the Easter Islands.

In it, they found an as-yet unknown compound secreted by a bacterium called Streptomyces hygroscopicus.

“Uma, it’s a fantastic compound, it’s a miracle,” Sehgal would tell his wife during these early encounters. “Anything it touches gives good results.”

“Uma, it’s a fantastic compound, it’s a miracle,” Sehgal would tell his wife during these early encounters. “Anything it touches gives good results.”

But in 1983, a shake-up at his company meant employees were laid off, researchers were moved to New Jersey, and rapamycin was no longer a “company priority.”

The last remaining vials of the drug were to be destroyed.

The last remaining vials of the drug were to be destroyed.

But Sehgal made one last batch and took it home, where he kept it by the ice-cream for FIVE years, until he had a chance to resume research.

Research on rapamycin resumed in 1989. Sehgal was desperate to get it out to the world.

Apart from running tests on it himself, he sent the compound to the best scientists and researchers around the world, asking that they study it.

Apart from running tests on it himself, he sent the compound to the best scientists and researchers around the world, asking that they study it.

One researcher even remembers how, along with the drug sample, Sehgal had also sent a little note wishing him luck. That became his inspiration.

The new research threw up exciting findings: it had potential application in cancer treatments, it could be a potential drug for organ transplantation, AND MORE.

FINALLY, IN 1999—the USFDA granted the licence to market rapamycin as a drug to prevent renal transplant rejection.

Rapamycin, with the brand name Rapamune, would finally be on the market.

Rapamycin, with the brand name Rapamune, would finally be on the market.

A year earlier, in 1998, Sehgal had felt something was off in his own body. It turned out to be stage 4 metastatic colon cancer. He was given six months to live.

He lived for five years.

His treatment? Chemotherapy, radiation—AND his own drug, rapamycin.

He lived for five years.

His treatment? Chemotherapy, radiation—AND his own drug, rapamycin.

One time, while he was recovering from treatment at a hospital in Pittsburgh, he was surrounded by liver transplant patients.

They somehow got to know the discoverer of the drug that had given them a new lease of life was on their floor.

People came in, one by one, some on wheelchairs, to shake his hand and thank him.

People came in, one by one, some on wheelchairs, to shake his hand and thank him.

Sometime during the last six months of his life, Sehgal developed a doubt: how was he to know if rapamycin was the reason for his good health? After all, he had undergone chemo and radiation too.

Soon, the scientist became the experiment.

Soon, the scientist became the experiment.

He stopped taking the drug and the cancer returned with a vengeance.

He was in immense pain, but he was working on a paper until five days before his death, with an oxygen mask on his face.

He was in immense pain, but he was working on a paper until five days before his death, with an oxygen mask on his face.

And on 21 January 2003, Sehgal died at home, surrounded by loved ones.

He didn't live to see his work change all these millions of lives, but he knew he'd made a difference.

He didn't live to see his work change all these millions of lives, but he knew he'd made a difference.

Rapamycin is still around, in use and under further study. Thanks to a lifetime of work Sehgal put in to convince the world that the molecule could indeed be life-saving.

He saw the magic in that molecule when no one else did.

He saw the magic in that molecule when no one else did.

For more, read @sukhadatatke's sci fi-like story of rapamycin the wonder drug, and the man behind it all: fiftytwo.in/story/man-of-c…

(Photo courtesy: the Sehgal family)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh