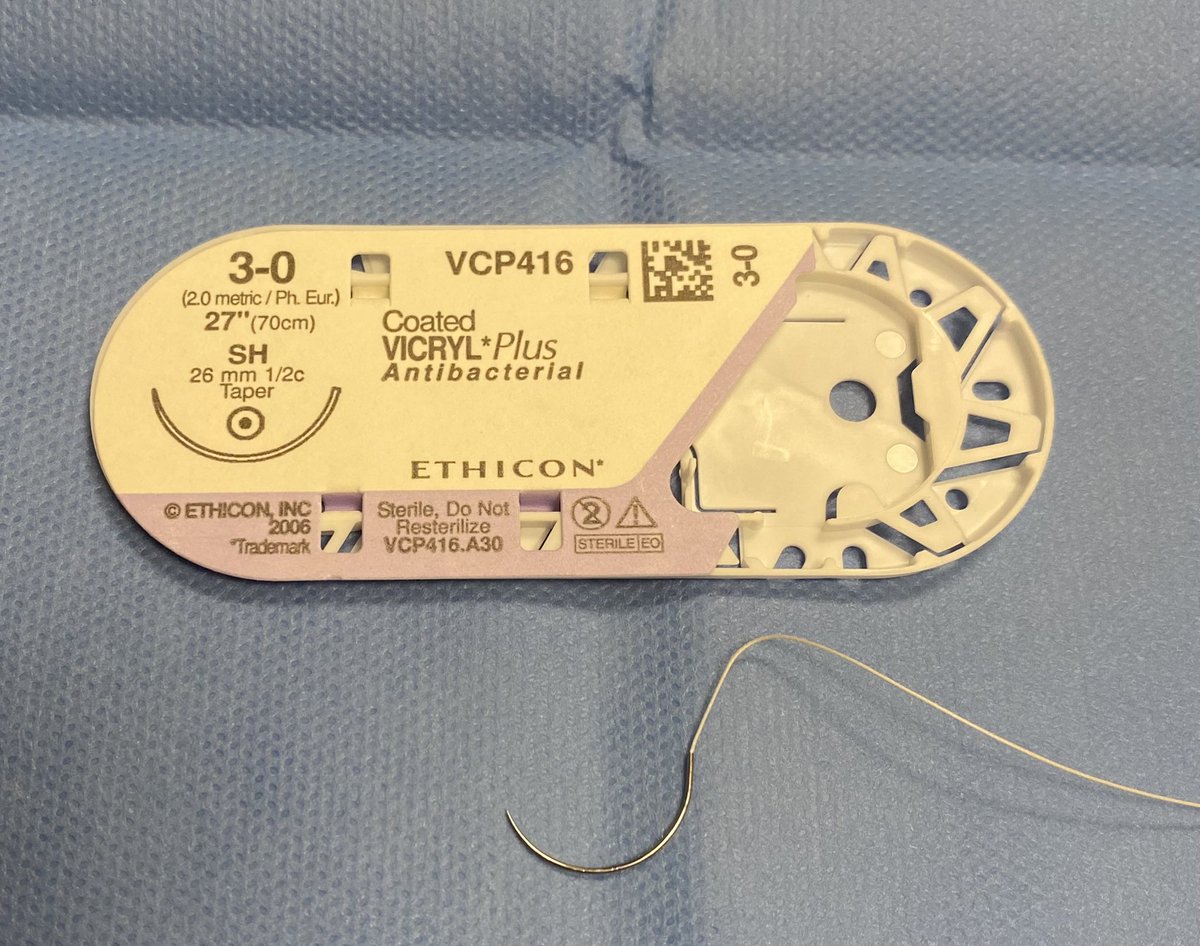

The ubiquitous SH needle, used for many applications.

It stands for ‘Small Half’ circle.

There are also MH, LH, XLH, and even XXLH…not shown here.

It turns out that all of the needle designations have a meaning…

Short 🧵.

It stands for ‘Small Half’ circle.

There are also MH, LH, XLH, and even XXLH…not shown here.

It turns out that all of the needle designations have a meaning…

Short 🧵.

CT stands for ‘Circle Taper’

Note these are tapered needles.

There is CT (40 mm) and then CT-1 is a little smaller at 36 mm.

There is also a CT-2 (not shown - it is 26 mm)

Note these are tapered needles.

There is CT (40 mm) and then CT-1 is a little smaller at 36 mm.

There is also a CT-2 (not shown - it is 26 mm)

PS stands for ‘plastic surgery’.

This is a PS-1.

It continues with PS-2 and PS-3, which are smaller. These are 3/8 circle.

PS-4, -5, and -6 exist, and these are slightly different at 1/2 circle.

This is a PS-1.

It continues with PS-2 and PS-3, which are smaller. These are 3/8 circle.

PS-4, -5, and -6 exist, and these are slightly different at 1/2 circle.

The famous UR-6 needle. It is 5/8 circle.

No tricks here—the UR stands for ‘urology’. I don’t know what they use it for, but general surgeons use it for closing fascia of 12 mm trocar sites.

UR-4 and UR-5 exist, and these are larger.

No tricks here—the UR stands for ‘urology’. I don’t know what they use it for, but general surgeons use it for closing fascia of 12 mm trocar sites.

UR-4 and UR-5 exist, and these are larger.

This symbol stands for ‘controlled release’.

In the US, we commonly call these ‘popoffs’. Perhaps they are called other things elsewhere.

These needles are designed to pop off when the suture is pulled.

In the US, we commonly call these ‘popoffs’. Perhaps they are called other things elsewhere.

These needles are designed to pop off when the suture is pulled.

This is a Keith needle. Very old-school here. In its current interation, it is a reverse cutting needle.

It is named for Thomas Keith, a surgeon in Edinburgh in the 19th century. He seemed to have led an interesting life that would be a good thread on its own.

It is named for Thomas Keith, a surgeon in Edinburgh in the 19th century. He seemed to have led an interesting life that would be a good thread on its own.

This is from the Ethicon Wound Closure manual, where I got some of this material. it shows all of the Ethicon codings for needles. Other brands sometimes use other codes.

Interestingly, I came across a 3-0 prolene on a Keith needle.

If anyone has an idea what this might be used for, I’d be interested. I don’t think I’ve seen it before.

If anyone has an idea what this might be used for, I’d be interested. I don’t think I’ve seen it before.

One may also obtain both straight and curved needles that do not have a suture on them. These are Richard-Allan needles.

I am not sure which specialties make regular use of these.

I am not sure which specialties make regular use of these.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh