As a bit of background I actually started to learn to fly at the age of 16, clocking up 20 hours and managing to go solo. My original plan was to become an airline pilot and see the world, which is why I studied aeronautics at university.

However at the time a large number of pilots were ex military and I didn’t really fancy that route. A few airlines like BA had training programs but they seemed to favour Oxbridge graduates from “good backgrounds”.

The other route was to pay for your own training, but that wasn’t really possible for a kid from a council estate. So I put my flight training on pause. However it was something I always wanted to pick up and finish so 30 years later here I am.

The PPL training was very slow going, in part because the UK weather. This is one of the reasons why a lot of the richer kids in my university course we t to the US for a few months to get their licences. Obviously that’s a lot harder to do now :(

By the end of the first summer I was back to doing solo circuits, then the weather closed in. By the end of the second summer I was doing solo cross country flights. Then the weather closed in again. I was planning to nail it by the third summer, but then the pandemic hit.

Amongst other things my flying school shut down which meant having to switch schools, planes and airfields. It took me pretty much the whole summer to get back to where I was previously. It was then a race to get my skills test done before the weather closed out.

Sadly I didn’t quite make it, which meant 6 months of no flying. So when I picked it up again this Spring, I was super rusty. By May I was back up to test scratch, but my test at the end of May had to be scrapped due to bad weather and I couldn’t get a new slot till yesterday.

I also didn’t have any lessons booked as I’d hoped to have been finished by then. Managed to squeeze a couple in before the test but was feeling pretty rusty.

The skills test involves planning and executing a flight with an examiner there to watch you, very much like a driving test. The first part of the test is just flying a route, making sure you can do all the RT calls, maintain height, separation etc.

The route I was given took me through Southampton controlled airspace. Controlled airspace in challenging at the best of times as they’re mostly dealing with big passenger jets and only letting you through if they think you sound like you know what your doing (apparently I did).

Once through controlled airspace and on the next phase of the route. I had to wear a visor that obscured the view, it order to simulate flying into a cloud, and I had to fly the plane on instruments only (which is surprisingly hard/disorientating).

I then had to plan a diversion which basically means flying the plane, plotting a new route on the paper map and making some on the fly calculations around speed and heading (to compensate the wind).

Had a slightly tricky moment where I had to take avoiding action to miss another plane, which almost push me into controlled airspace again (which would have been a problem). However the examiner said that I handled the situation well.

We then flew down to The Solent, trying to stay under the 2,000ft airspace above. When we got to The Isle of Wight I had to perform three different stalling techniques to simulate what you’d do of the airplane lost lift. I then had to recover from a spiral dive.

Just like a driving test where the examiner hits the dashboard and tells you to stop, during the skills test the examiner will pull the power and tell you you’ve had an engine failure.

You need to go through a series of memories checks to see if you can restart the engine. If not you need to set the plane up for a glide, find a suitable field, make a simulated Mayday call and set up for a Practiced Forced Landing on a field.

This was the bit of the test I was dreading the most as it’s basically a fail if you get this wrong, which many do. Fortunately luck was on my side. I picked a good field, got my hight right and got set up perfectly.

As we were climbing away the examiner pulled the throttle again to simulate an engine failure after take off, and I had to go through a cut down version of the process once again. A little less slick this time but safe enough.

Getting to the end now, as a I followed a VOR radio navigation aid back to the field, joined overhead and then entered the circuit where I had to do three different landings. A regular approach, a glide approach and a flawless approach.

It was a super hot day yesterday which meant the air was very bumpy and had lots of thermals. This made it quite difficult loosing the necessary hight on final, and caused me to initiate a “go around” on the glide approach. Fortunately I got it down on the next try.

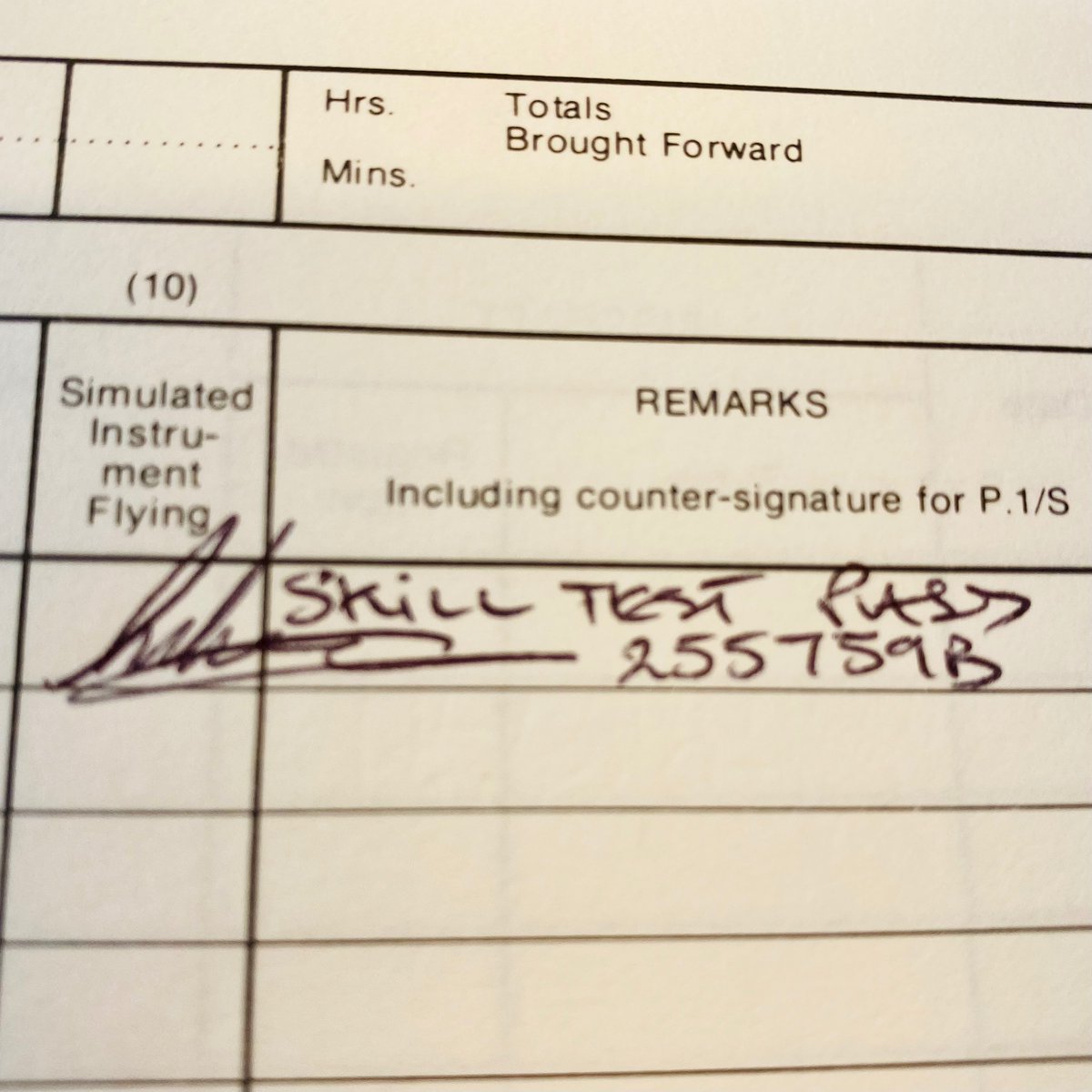

Total flying time 2:10. Pretty bloody exhausting. Examiner was happy. Had a few small pointers but nothing major, so it looks like all the hard work paid off.

Flawless not flawless :)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh