Last month @AOC mentioned the Jones Act on her Insta (

But that just scratches the surface. Let's do a deep dive into the history of the JA's impact on 🇵🇷 (🧵).

https://twitter.com/cpgrabow/status/1534154526009315329), linking to this 2017 @latimes piece about the law & Puerto Rico: latimes.com/nation/la-na-j…

But that just scratches the surface. Let's do a deep dive into the history of the JA's impact on 🇵🇷 (🧵).

An armistice signed by Spain on August 13, 1898 during the 🇪🇸-🇺🇸 War relinquished control of Puerto Rico. Two days later 🇵🇷 was placed under coastwise laws requiring the use of US vessels for transport b/w the island and US ports as a "military measure": drive.google.com/file/d/1vTAWre…

The war formally ended with the Treaty of Paris (December 1898), Article II of which handed control of Puerto Rico to the US: avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/s… The next month legislation was introduced in Congress making 🇵🇷 subject to US coastwise laws. drive.google.com/file/d/1ghMFus…

Noting a lack of US ships to handle 🇵🇷's trade, a Nov 1898 @nytimes opinion piece called the decision to apply coastwise laws a "blunder" of "proportions really colossal" while a Jan 1899 piece called it a "ridiculous prohibition". drive.google.com/file/d/1NPvMRS… drive.google.com/file/d/1m0_Qqe…

In May 1899 an executive order was issued in allowing foreign vessels to temporarily engage in coastwise trade between Puerto Rico and other U.S. ports. This is likely indicative of the disruptions caused by subjecting the island to U.S coastwise laws. drive.google.com/file/d/1BFBDuJ…

Disruptions wouldn't have been surprising given 🇵🇷's lack of interest in using 🇺🇸 shipping pre-1898. Writing in July 1899, Worthington C. Ford noted that US ships transported only 16% of PR's imports from the US and 22% of exports to the mainland. drive.google.com/file/d/1Ek_Lrv…

This lack of interest was likely due to US ships' expense. In February 1900 a delegation of Puerto Ricans presented a petition to Congress calling the freight rates on US vessels "well nigh prohibitive" and the coastwise shipping laws "a grievous hardship to Puerto Rico."

A copy of that petition can be found here: drive.google.com/file/d/1iC1n51…

The delegation also made the same point in a @nytimes

op-ed that same month: drive.google.com/file/d/13H9J5Y…

The delegation also made the same point in a @nytimes

op-ed that same month: drive.google.com/file/d/13H9J5Y…

Among those in the delegation: Luis Sánchez Morales (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luis_S%C3…) who would later become the second president of the Puerto Rico Senate and Tulio Larrínaga, (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulio_Lar…) a future Resident Commissioner (non-voting member of Congress from Puerto Rico).

The petitioner's pleas for relief from U.S. coastwise laws were ignored. Section 9 of the Foraker Act—passed in April 1900 to establish a civilian government in Puerto Rico—affirmed that the island was subject to U.S. coastwise laws: loveman.sdsu.edu/docs/1900Forak…

In June 1920 the Jones Act was passed. The law didn't change much for Puerto Rico as it has long been subject to U.S. coastwise laws. Indeed, the principal target of the Jones Act was Alaska: alaskapolicyforum.org/2021/12/alaska…

Ten years later a book entitled "Porto Rico and its Problems" published by @BrookingsInst identified U.S. coastwise laws (i.e. the Jones Act) as a hindrance to the island: quod.lib.umich.edu/p/philamer/agd…

The 1931 book "Porto Rico: a Broken Pledge" went into greater detail, noting many of the high shipping rates paid by Puerto Rico compared to elsewhere. But it also pointed out some disadvantages not captured by published shipping rates: drive.google.com/file/d/1pZU2gE…

In 1941 the US entered World War II and the Jones Act—which some supporters today claim helps keep enemy spies and saboteurs out of critical U.S. waterways—was suspended in September 1942 for transportation between Puerto Rico and the rest of the US: govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR…

At the war's conclusion, the Jones Act was reimposed. In 1951 legislation was introduced to try to alleviate the law's burden by allowing subsidized U.S. ships engaged in foreign trade to also transport goods to and from Puerto Rico: drive.google.com/file/d/1o8IVgS…

It did not pass.

It did not pass.

Such was the Jones Act's burden on Puerto Rico that a 1956 thesis paper noted that the law's revision or cancellation was a goal of all political groups on the island: drive.google.com/file/d/1F1v9fx…

In 1961 hearings were held on "The Problems of the Noncontiguous Areas Shipping Industry and the Economic Impact on the Offshore Areas Served." Puerto Rico's Governor Luis Muñoz Marín testified via a letter to Congress. drive.google.com/file/d/1K5G5xf…

"There is no single problem of greater economic consequence to the people of Puerto Rico than the problem which you have determined to investigate and remedy: the deepening crisis of our offshore shipping services," Gov. Muñoz wrote.

Teodoro Moscoso, known for his leading role in Operation Bootstrap (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation…) meant to promote Puerto Rico's industrialization, testified that high freight rates hampered this development effort.

In 1965 the United States-Puerto Rico Commission held hearings about the island's economy. Economist Robert R. Nathan (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_R.…) noted in his testimony that Puerto Rico faced high shipping rates. drive.google.com/file/d/1sYhsc6…

Eduardo R. Gracia, a transportation economist, also testified that it cost Puerto Rico $10.4-$12.4 million annually to support the US merchant marine via the Jones Act. This amount, he added, was about 4 times greater than the average American.

Others would make similar points. At a 1989 congressional hearing, a representative of the Puerto Rico Manufacturers Association noted that the burden of supporting the merchant marine fell heavily on a community with high unemployment and low income: drive.google.com/file/d/1ho8cQ_…

Puerto Rico's Resident Commissioner Antonio J. Colorado also raised drew attention to this disproportionate burden at a 1992 hearing: drive.google.com/file/d/1ho8cQ_…

The repeated remarks about this unfairness, however, appear to have fallen on deaf ears.

The repeated remarks about this unfairness, however, appear to have fallen on deaf ears.

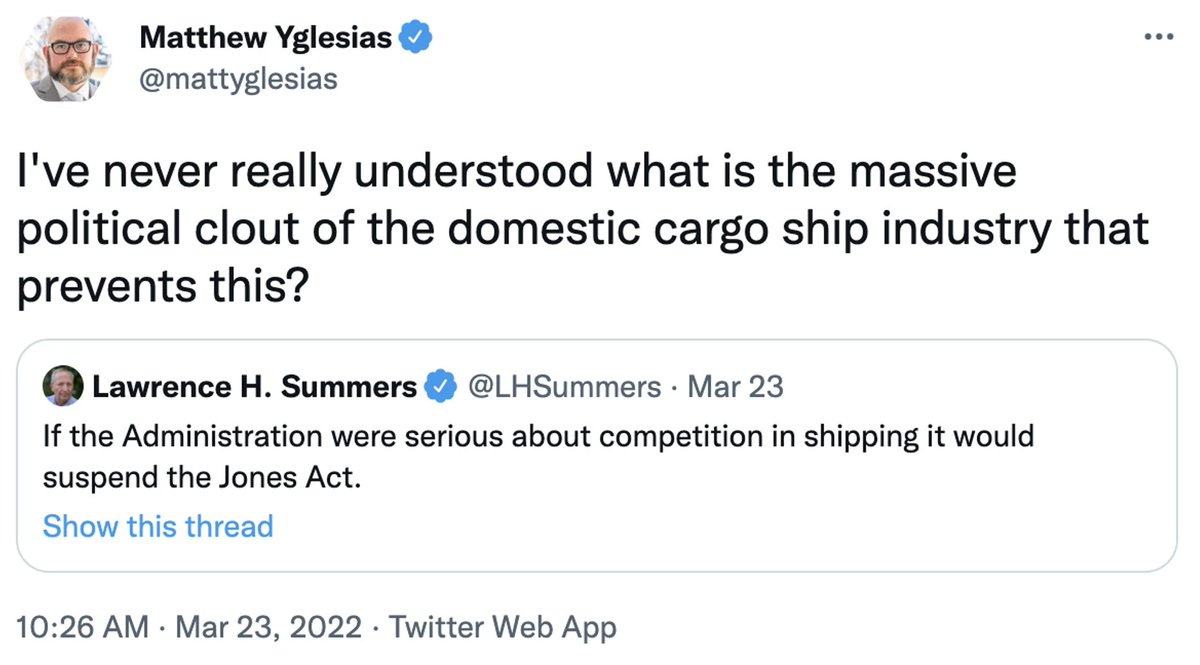

Notably, the high shipping rates paid by Puerto Ricans to support the US merchant marine haven't resulted in the employment of many ships. Only 5 ships are used for container transport to 🇵🇷, divided among @NatShipUS (1 ship), @CrowleyMaritime (2), and @TOTE_Maritime (2).

As the government of Puerto Rico noted in a 1996 report, "the [Puerto Rico] trade has increasingly become a trade served by barge; the self-propelled vessels are old and exceedingly expensive to replace in U.S. yards." drive.google.com/file/d/1P4tlZl…

Expensive indeed. The last two ships delivered for use in the Puerto Rico trade, the EL COQUI and the TAINO operated by @CrowleyMaritime, cost nearly $415 million ($207.3 million each): gcaptain.com/crowley-seeks-…

Such ships would likely have cost ~1/4 as much if built overseas.

Such ships would likely have cost ~1/4 as much if built overseas.

In the early 2000s Puerto Rico entered a period of economic stagnation (data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.G…) that has continued to the present day, prompting numerous studies and reports on how to restart growth. Many of them mention the Jones Act.

The 2007 book "The Economy of Puerto Rico: Restoring Growth" (amazon.com/Economy-Puerto…) for example, described the JA as effectively a tariff between PR and the U.S. mainland and also handicapped its ability to become a business logistics center.

A 2012 @NewYorkFed report about Puerto Rico's economy noted that JA shipping rates cost roughly 2x as much as to neighboring islands and that Kingston, Jamaica's port handled more containers despite the country having a smaller population: newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/m…

A 2013 @USGAO report about the JA's impact on 🇵🇷 declined to render any definitive judgment about its cost. But it did note distortions from the law, such as PR purchasing jet fuel from Venezuela and agricultural products from 🇨🇦 instead of the US: gao.gov/assets/gao-13-…

In early 2015 Puerto Rico's government commissioned a team of economists led by Dr. Anne Krueger (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne_Osbo…) to undertake a comprehensive analysis of Puerto Rico’s fiscal and economic challenges. They produced a report available here: drive.google.com/file/d/148FWLP…

The 2020 @RANDCorporation study "Challenges and Opportunities for the Puerto Rico Economy" also mentioned the Jones Act as a top challenge: rand.org/pubs/research_… In fact, a keyword search for "Jones Act" shows it appearing in the report 134 times.

A draft recovery plan put together by Puerto Rico's government in 2018 after Hurricane Maria also mentioned the Jones Act, stating that the law's reform could positively impact the local economy: drive.google.com/file/d/1Gp9gu8…

For having the temerity to mention the Jones Act, Rep. Duncan Hunter—who at the time was chairman of the House Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation Subcommittee—sent a sharp rebuke to the report's authors: drive.google.com/file/d/1FlCY5c…

Hunter included in his response a copy of a study funded by the pro-JA @AMPmaritime concluding the JA imposed no cost to consumers in 🇵🇷. The methodology consisted of comparing online prices for 13 items at Walmart locations in San Juan and Jax, FL. cato.org/blog/no-jones-…

Congress's blind eye to the JA's harm is typical. When a Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in Puerto Rico issued its report on federal impediments to economic growth in late 2016 the Jones Act wasn't mentioned even once: finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/…

Rep. Hunter and other members of Congress also rallied to the Jones Act's defense after Hurricane Maria in 2017, holding a "listening session" that effectively served as a platform for Jones Act lobbyists to argue against a waiver of the law to help 🇵🇷:

https://twitter.com/cpgrabow/status/1310636954946592769

That members of Congress would back the shipping industry and not even mention the Jones Act in its report on 🇵🇷's economy is all the more notable given that less than a decade earlier JA shipping companies operating in 🇵🇷 had pled guilty to price-fixing: justice.gov/archive/atr/pu…

The good news is that these efforts to stop the 2017 waiver weren't successful. The Jones Act was suspended for ten days, allowing ten foreign ships to transport supplies to Puerto Rico from the U.S. mainland after Hurricane Maria: drive.google.com/file/d/1twdQ0I…

The next year the government of Puerto Rico filed a request to get another Jones Act waiver, this time for the transportation of liquified natural gas (LNG). A copy of the request (obtained via FOIA) is available here: drive.google.com/file/d/1XVHpkF…

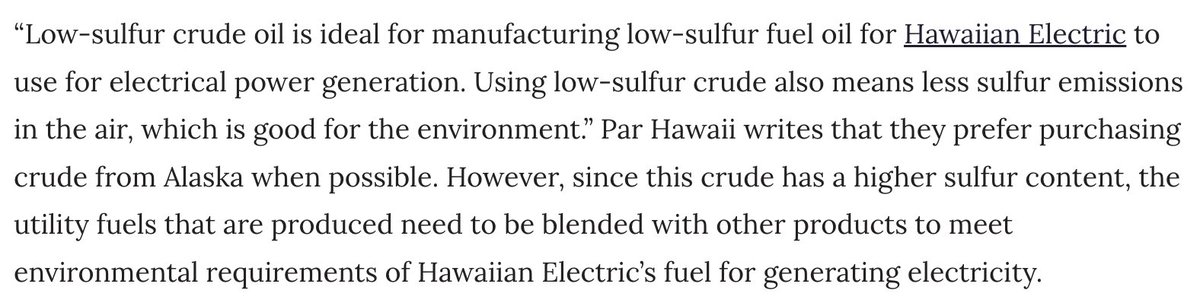

In FY 2021 Puerto Rico used natural gas for 44% of its electricity generation. Despite a domestic abundance of natural gas, however, Puerto Rico must source it from abroad due to a total lack of LNG tankers in the Jones Act fleet to transport it from the U.S. mainland.

Most of the imported LNG comes from Trinidad and Tobago, but tankers have also arrived from other places including Algeria, France, Spain, and Brazil. In 2019 a tanker arrived from Belgium carrying gas that originated in Russia: bloomberg.com/news/articles/…

This inability to source U.S. LNG comes at an economic cost to Puerto Rico, with the head of the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority testifying in 2019 that it results in lost savings of hundreds of millions of dollars: naturalresources.house.gov/imo/media/doc/…

A contract signed by PREPA in 2020 for LNG supplies provided for an automatic price reduction should LNG shipments no longer be subject to the Jones Act: drive.google.com/file/d/1tWwheb…

Despite the potential savings to Puerto Rico and the lack of LNG carriers in the JA fleet, Puerto Rico's LNG waiver request was denied in 2019: drive.google.com/file/d/1ex3Okk…

The decision likely pleased many members of Congress. Earlier that year members of the FL delegation sent a letter opposing the waiver, insisting that such a waiver *making it easier for Puerto Rico to buy U.S. LNG* would "devastate FL's LNG industry": drive.google.com/file/d/1I4pd8l…

It's now 2022 and Puerto Rico's government appears set to once again request a waiver to buy American natural gas: elnuevodia.com/noticias/local…

With U.S. LNG off-limits Puerto Rico recently imported LNG from Oman:

With U.S. LNG off-limits Puerto Rico recently imported LNG from Oman:

https://twitter.com/cpgrabow/status/1534904626406998017

So that's an overview of the Jones Act's historical impact on Puerto Rico. It's quite evident that the law and the coastwise restrictions that preceded it have harmed the island since it became part of the United States.

Puerto Rico has a 43% poverty rate and a per capita GDP ~$10K less than Mississippi, the lowest-ranked US state in this category. Granting 🇵🇷 a JA exemption wouldn't be a silver bullet for the island's problems, but it would help. Congress should do it. (/insanely long 🧵)

please unroll @threadreaderapp

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh