Just accepted @EvolHumBehav: @HSB_Lab & I argue for social diversity during the Late Pleistocene w/ bigger groups, more hierarchy, etc. Preprint & summary in this older 🧵, so I’ll focus on how our argument differs from @DavidWengrow's #TheDawnOfEverything

https://mobile.twitter.com/mnvrsngh/status/1371466783035564036

Like @DavidGraeber & @DavidWengrow, we argue that the classic story (small, mobile, egalitarian bands before agriculture) needs a facelift. We point to some similar evidence (e.g., social flexibility & diversity among Holocene hunter-gatherers). Yet there are 4 major differences:

(1) We draw on (& embrace) behavioral ecology, which analyzes behavior using an evolutionary & ecological lens. In contrast to G&W, we argue that ecology shapes societies, w/ dense, reliable (esp. aquatic) resources more often sustaining larger, sedentary, stratified groups.

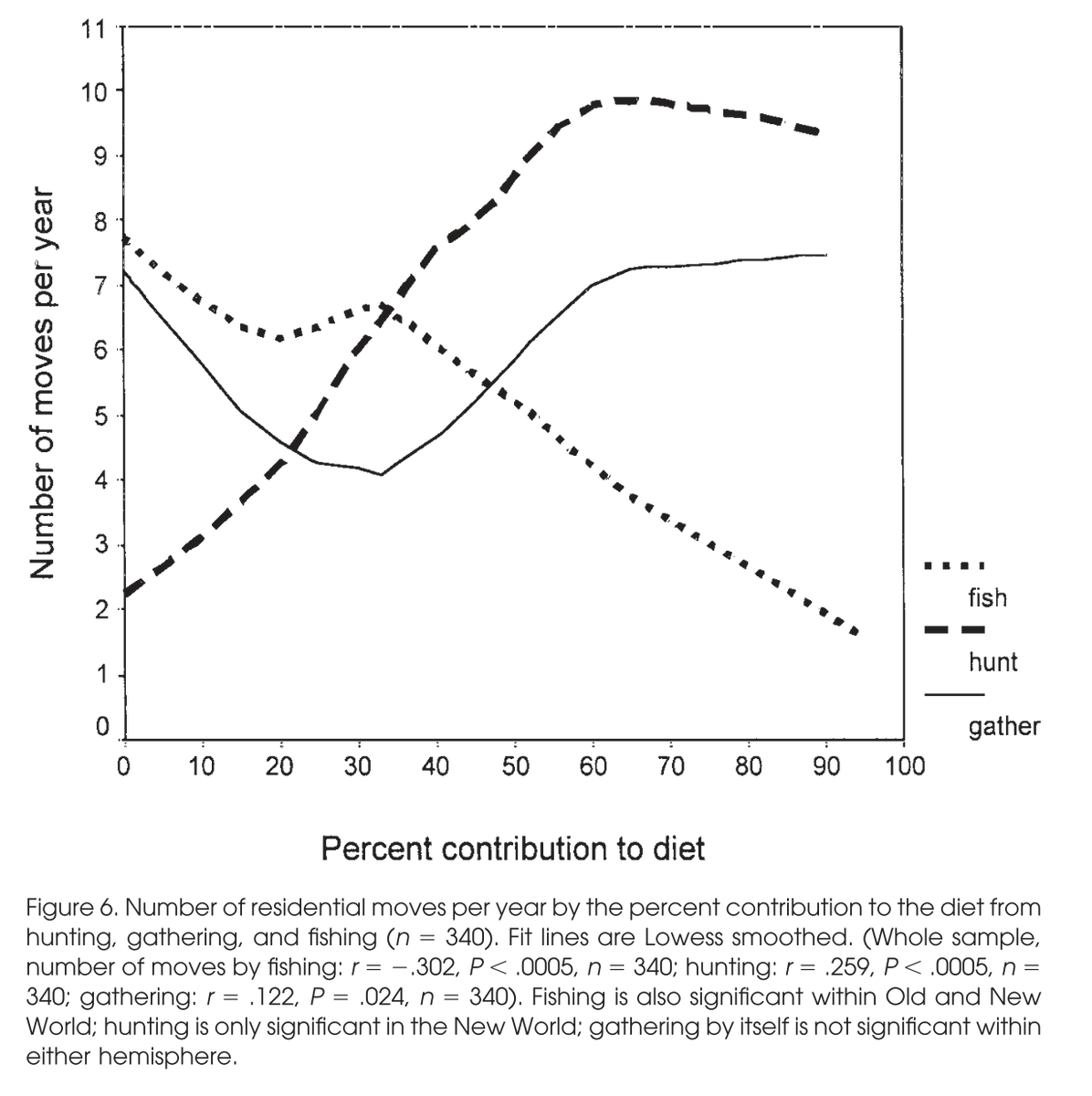

This is corroborated by comparative studies. See the plot (left) by Marlowe (2005): Across 340 forager societies, more fish means fewer moves/year. Or look at Codding & Smith (2020) (right): Across 89 Pacific Coast foragers, more aquatic resources predicts more hierarchy.

(2) We dwell on Africa. There are few direct signs of social diversity in Africa during the Late Pleistocene (~130k-12k yrs ago). So we turn to ecology. We synthesize research showing that ppl subsisted on resources (esp. coastal) that tend to sustain big groups, hierarchy, etc.

In fact, I'd argue it's hard to reconstruct Pleistocene societies w/o turning to diet & ecology. The basic problem is inferring past societies using recent analogues—yet how do we know which analogues to use? Behavioral ecology provides an empirically-informed framework.

(3) We argue there are implications for our evolved psychology. We conclude that human minds are not exclusively adapted for living in small, mobile, egalitarian bands. Rather, our psychology is much more flexible, equipped to traverse a much broader set of social circumstances.

Admittedly, G&W don't seem interested in implications for evolutionary understandings of behavior. Given how much the 'nomadic-egalitarian model' has impacted evolutionary anthro & evolutionary psych, however, we think that there's a lot of room for reconsideration here.

(4) G&W conclude that most of human history was characterized by 3 freedoms: freedom to move, freedom to disobey, & freedom to reconfigure social relationships. Presumably, these freedoms have largely disappeared. But there's little we've come across to suggest this narrative.

If anything, I wonder whether the story about the three freedoms replaces one 'noble savage' myth (nomadic-egalitarian) with another (über-free). But I look forward to empirical research that more systematically evaluates the claim.

Differences aside, our aims are similar: using archaeology + ethnography to question common assumptions about deep history & build better models. And regardless, G&W are forcing social scientists to contend w/ social diversity & flexibility in a way few big-picture thinkers have.

Again, here's the preprint (no paywall): ecoevorxiv.org/vusye/

And here's an older thread summarizing the paper. The manuscript has evolved in the last year, but the basic points are largely the same:

And here's an older thread summarizing the paper. The manuscript has evolved in the last year, but the basic points are largely the same:

https://mobile.twitter.com/mnvrsngh/status/1371466783035564036

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh