Sorry. I just have to revisit this one more time.

The main point of this article seems to be to advocate publicly funded countercyclical home building as a solution to our housing shortage.

This is an untenable political goal in search of a purpose.

1/

The main point of this article seems to be to advocate publicly funded countercyclical home building as a solution to our housing shortage.

This is an untenable political goal in search of a purpose.

1/

https://twitter.com/KAErdmann/status/1550970235913506818

Let's take a look at Phoenix and LA in 2010.

In neither case does closing the cyclical gap in local construction solve any actual problem. Phoenix had a collapse in demand and mass vacancies at the time, ....

2/

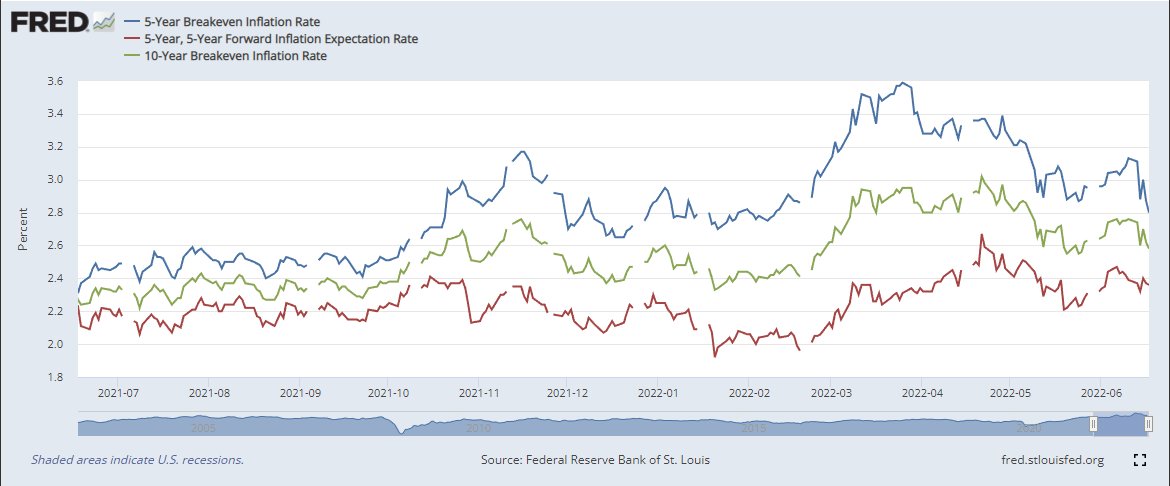

fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=S7Hi #FRED @stlouisfed

In neither case does closing the cyclical gap in local construction solve any actual problem. Phoenix had a collapse in demand and mass vacancies at the time, ....

2/

fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=S7Hi #FRED @stlouisfed

...and countercyclical building in LA gets them all the way up to the level of building in Phoenix in 2010 when the metro was in crisis.

The solution we need is for LA to be MORE cyclical - for building in LA in 2005 to be 5 times what it was!

3/

The solution we need is for LA to be MORE cyclical - for building in LA in 2005 to be 5 times what it was!

3/

If anyone wants to steelman the article, I'll let you have the last word, because these are two thoughtful writers on this topic and they have earned better than dismay, which is the best I can do on this.

4/4

4/4

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh