If Byzantium can be given a starting date, it’s today’s date in 636, when it suffered one of its worst ever defeats at the Battle of the Yarmouk.

This marked the end of a cosmopolitan Mediterranean hegemon and left a mostly Greek, Orthodox holdout of the Roman state. Thread.

This marked the end of a cosmopolitan Mediterranean hegemon and left a mostly Greek, Orthodox holdout of the Roman state. Thread.

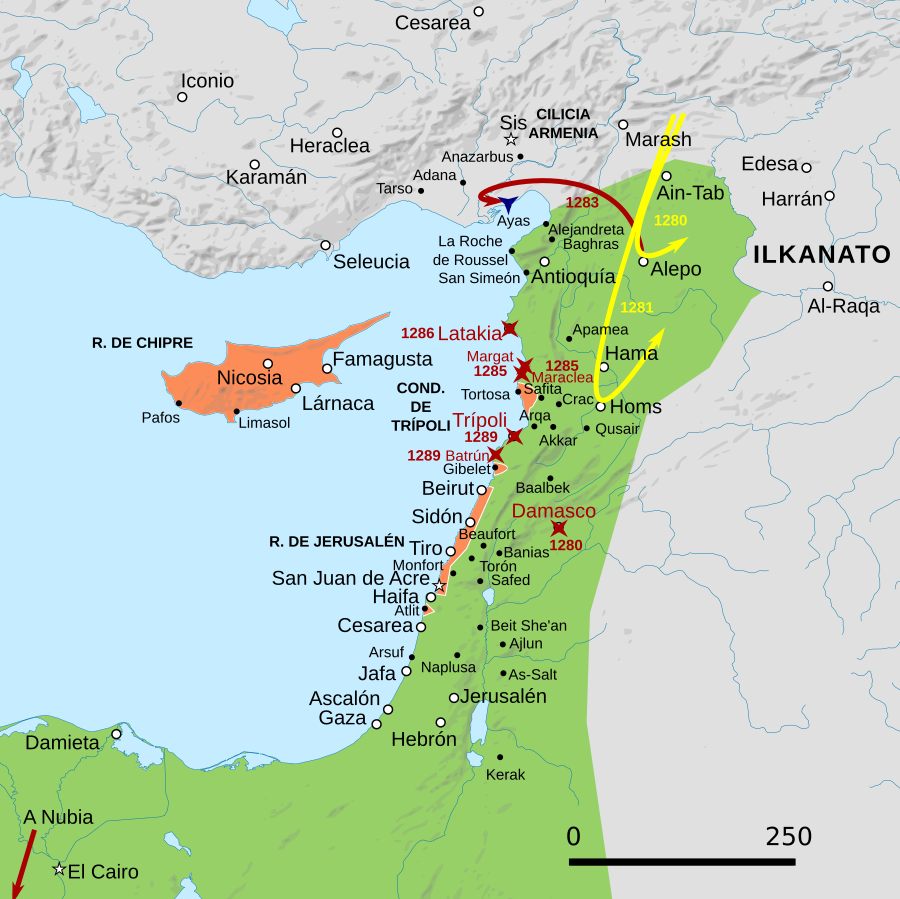

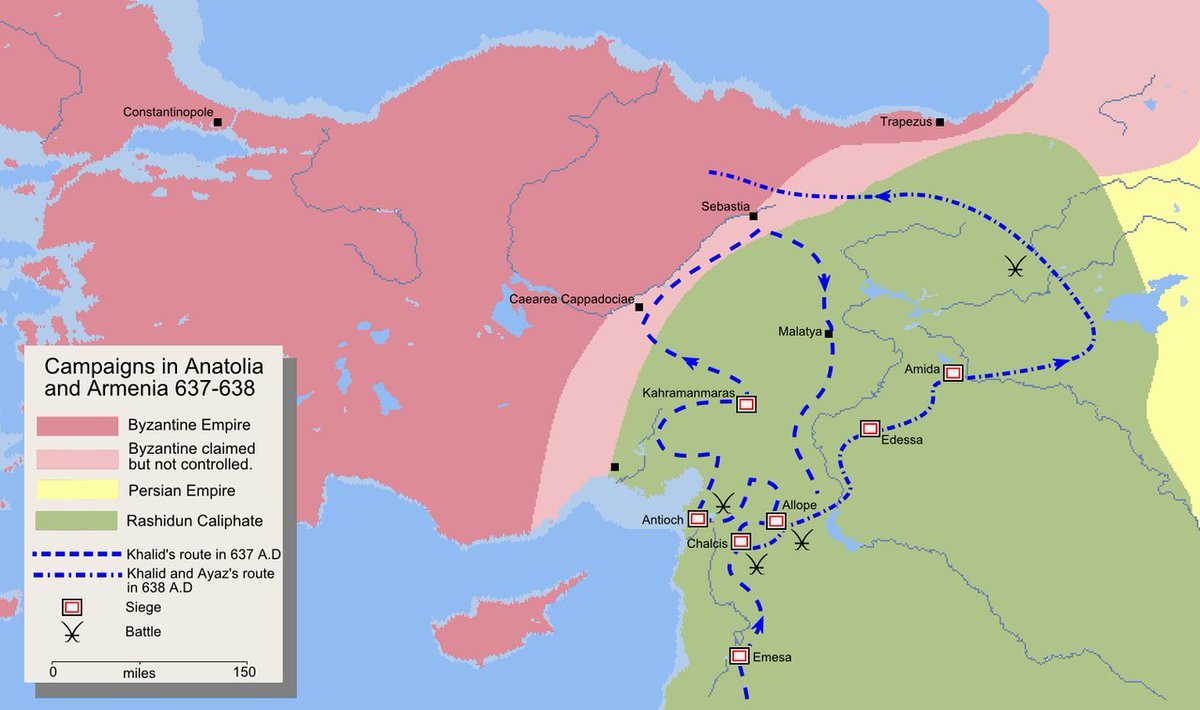

Islam’s expansion out of Arabia in the 630s came on the heels of the massive Roman-Sasanian War, which exhausted both empires. By the end of 634 the Muslims had conquered southern Syria and most of Palestine, and in 636 they reached as far as Homs.

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1496208931584106496

These early reverses did not mean the Romans were by any means broken. That same year Heraclius summons an enormous army, composed of elements from the standing armies of Armenia, the East, and various mercenary contingents, even Persians.

There’s a ton of conflicting evidence about events, so I’ll largely follow Kaegi’s “Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests” and Haldon’s “The Byzantine Wars”, which are the best reconstructions.

Beginning in the spring of 636, the elements of the Roman army march south and drive the Arabs out of first Homs (Emesa) and then Damascus. This is a large-scale campaign, consisting of many independent smaller actions.

Eventually they drive the Muslims back to the Hauran, a fertile region east of the Jordan which could sustain large concentrations of troops.

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1382364377723076612

By the end of July, the Romans are positioned on the southern slopes of the Golan Heights, while the Muslims encamp just north of the Yarmouk River.

They are separated by the steep gorges of the Wadi'l Ruqqad.

They are separated by the steep gorges of the Wadi'l Ruqqad.

There is skirmishing over the next few weeks, and the Romans divide their forces into two wings:

-The right is encamped just west of the Wadi’l Ruqqad’s confluence with the Yarmouk.

-The left is east of the Wadi’l Ruqqad, with open country to its rear.

-The right is encamped just west of the Wadi’l Ruqqad’s confluence with the Yarmouk.

-The left is east of the Wadi’l Ruqqad, with open country to its rear.

One point to be emphasized is that the battlefield was *huge*—the two Roman camps are separated by about 20 miles (30 km). Yarmouk should not be understood as a single battle, but as a large-scale operation designed to entrap the Arab army.

Although the Arabs often liked to fight with the desert to their backs, this was usually as an expedient, not a special weapon. It would still be very costly if they were forced to retreat over the Yarmouk and through the desert.

Numbers are impossible to estimate. Muslim sources range between 40,000 and 400,000 for the Romans, while both sides agree the Arabs had fewer. Kaegi & Haldon estimate no more than 20,000 Romans against rather fewer for the Muslims.

Given the size of the battlefield, the ability of the region to sustain large armies, and the need to draw troops from as far away as Armenia, however, I suspect the true number was a good bit larger.

The two sides appear to have faced off for several weeks, probably skirmishing the whole time. But on August 18 or 19, the Romans advance: the left moves south, the right crosses the Wadi’l Ruqqad, and their Ghassanid Arab allies occupy a bridge in the center.

The main attack comes in the east. The Muslims make a great show of abandoning their camp, but then counterattack from a hidden position. Arab cavalry outflanks the Romans and drives the Ghassanids off the bridge, cutting the Roman left off from its other wing.

Meanwhile Muslim forces on the left get around the western flank of the Roman position and attack the right’s camp. As night falls, the Roman right is completely isolated.

Over the next day or two, the Muslim forces converge on the isolated Roman right and strangle it. A sandstorm whips up on the 20th, and all remaining discipline is lost: desperate soldiers try to scramble down the steep ravines of the Wadi’l Ruqqad and are slaughtered.

It’s a complete disaster for the Romans, as their entire field army has effectively been destroyed. The Arabs go on to besiege Damascus, Jerusalem, Homs, and the entire coast.

Heraclius raises an army from allies to recapture Homs two years later, but this fails.

Heraclius raises an army from allies to recapture Homs two years later, but this fails.

By the end of 638, the Romans have lost all of Syria, Mesopotamia, and Armenia, and are fighting off incursions into Anatolia itself.

By 650, the empire is reduced to Anatolia, part of the Balkans, parts of Italy, and North Africa.

The Lombards are expanding in Italy, while the Arabs will soon capture the entire African coast.

The Lombards are expanding in Italy, while the Arabs will soon capture the entire African coast.

This means that most of the remaining population is Greek-speaking and orthodox Chalcedonian. The large heterodox Egyptian, Syrian, and Armenian miaphysite populations have been shorn away, while Constantinople still controls the papacy—and Italy is increasingly peripheral.

It is this core, Greek in language, Orthodox in religion, and Roman in government, which will survive and rebound over the next few centuries, creating a distinctive and new civilization in the process—what we now call Byzantium.

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1236740282072412161

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh