Another great early science result from #JWST: the first unambiguous detection of CO2 in the atmosphere of an exoplanet.

Seen in one single transit of the planet WASP-39b in front of its star with the @esa-led NIRSpec instrument.

So much more to come.

esa.int/Science_Explor…

Seen in one single transit of the planet WASP-39b in front of its star with the @esa-led NIRSpec instrument.

So much more to come.

esa.int/Science_Explor…

@esa This result comes from one of the Early Release Science programmes & is fully described in a paper that came out on arXiv overnight & will be published in Nature next week.

Congratulations to the large team of authors & everyone who made this possible.

arxiv.org/abs/2208.11692

Congratulations to the large team of authors & everyone who made this possible.

arxiv.org/abs/2208.11692

@esa To add a bit of background here, the gas planet WASP-39b blocks about 2.5% of the light of its host star as it crosses in front of it from our perspective.

You can see that clearly in the top curve, which is about eight hours long – the transit takes about three.

You can see that clearly in the top curve, which is about eight hours long – the transit takes about three.

@esa But certain gases in the atmosphere of the planet absorb the starlight at specific wavelengths, making the planet appear fractionally larger at those wavelengths.

So by measuring the depth of the transit as a function of wavelength, you can derive a spectrum for its atmosphere.

So by measuring the depth of the transit as a function of wavelength, you can derive a spectrum for its atmosphere.

@esa That spectrum for WASP-39b shows a dip at around 4.4 microns due to carbon dioxide. The spectrum is then inverted to show the "abundance" of CO2 as a bump, as seen in the first figure in this thread.

@esa In this case, the amount of CO2 is important to help understand the atmosphere of a gas giant planet: WASP-39b has a mass similar to Saturn but is puffed up bigger than Jupiter because it's very close to its star & heated to ~900ºC.

@esa The amount of CO2 seen here is fit by models of a planet with roughly ten times the abundance of heavier elements ("metals") than in our solar system.

The atmosphere should also show H2O, CO, & H2S, but little CH4 – future work on this object should test that prediction.

The atmosphere should also show H2O, CO, & H2S, but little CH4 – future work on this object should test that prediction.

@esa And of course CO2 is an important molecule for understanding terrestrial planets like Earth, where it is a trace gas (albeit a very important one) versus Mars & Venus, where it is the dominant atmsopheric species. Excellent spectra of several different molecules are key for that.

@esa On the technical side, this is a great achievement for #JWST, NIRSpec, & all involved. Transit spectroscopy is generally dominated by myriad sources of noise which have to be careful characterised & removed to tease out the tiny atmospheric gas absorption signals.

@esa That means a lot of work is needed before such spectra can be reliably extracted & usually the light curves from many transit events have to be added to get enough signals-to-noise.

Heroic efforts in this area has been made with data from Hubble & Spitzer, for example.

Heroic efforts in this area has been made with data from Hubble & Spitzer, for example.

@esa And yet this discovery from #JWST, derived from a single transit with a brand new telescope & instrument that were only commissioned less than two months ago, show just how revolutionary it is going to be in this field.

@esa Transit survey telescopes like Kepler, WASP, & TESS have discovered many exciting exoplanets, from gas & ice giants to rocky worlds, which #JWST will be able to measure the atmospheres of. Some will be in the habitable zone of their stars, like some of the TRAPPIST planets.

@esa Further detailed characterisation of the telescope & instruments, plus the addition of data from multiple transits, promises much more sensitivity to a range of molecules which will help us understand the properties of those planets & perhaps whether some could even host life.

@esa To be clear, it's unlikely that #JWST will be able to detect unambiguous signs of life itself, at least as we know it.

But it will provide us with many great places where at least the atmospheric conditions could be suitable to host life, to be studied with future missions.

But it will provide us with many great places where at least the atmospheric conditions could be suitable to host life, to be studied with future missions.

@esa And in this decade, #JWST will be joined by @esa's @ESA_Plato & @ESAArielMission, the former to survey nearby stars for many more transiting exoplanets & the latter dedicated to studying their atmospheres through this transit spectroscopy technique.

@esa @ESA_Plato @ESAArielMission After all, as great as #JWST is proving to be as an exoplanet spectroscopy machine even at this early stage, it has plenty of other science to cover from planets, moons, asteroids, & comets in our Solar System to the very first stars & galaxies that formed after the Big Bang.

@esa @ESA_Plato @ESAArielMission And of course, stuff in between in our Milky Way galaxy & others.

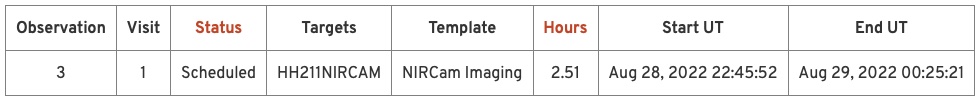

Including my first observations with #JWST of the HH211 protostellar jet system coming up on Sunday night 🙂

Including my first observations with #JWST of the HH211 protostellar jet system coming up on Sunday night 🙂

https://twitter.com/markmccaughrean/status/1560370505710030853?s=20&t=-XQptps13Ed6GI3TPK2YhA

What a privilege it is to be involved with this mission, not only because of the amazing science, but because it shows us what is possible when people come together across many countries & work for decades to achieve something that seemed impossible.

A real lesson for today.

A real lesson for today.

Coda: a gratuitous artist impression of WASP-39b, the subject of today's announcement & paper. It orbits its roughly Sun-like parent star every four days.

Not somewhere you'd want to move to to escape global warming.

More at the @esa webpage below.

esa.int/Science_Explor…

Not somewhere you'd want to move to to escape global warming.

More at the @esa webpage below.

esa.int/Science_Explor…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh