Liverpool’s most important historic site receives Scheduled Monument recognition and protection.

“It is one of the most important historic sites in world history” proclaims historian Dan Snow. So why doesn’t anyone in Liverpool know about it?

“It is one of the most important historic sites in world history” proclaims historian Dan Snow. So why doesn’t anyone in Liverpool know about it?

Hidden away in a quiet corner of Edge Hill in Liverpool is the original station complex of the world’s first modern railway. Opened in 1830, this section of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was superseded six years later by Lime Street Station.

it continued to be used for goods traffic until the 1970s, and occasionally since then. It is hidden away in a secluded location, and because of it being an active railway, there is no public access, and its history is not specifically covered in schools or books.

The original structures surrounding the line have become overgrown and damaged by vegetation, causing the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Trust to request that it receive the same level of protection as other irreplaceable historic sites.

This happened on Monday the 22nd of August when the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport approved the site's listing as a Scheduled Monument, the same designation as ancient sites like Stonehenge and Sutton Hoo.

Opened on the 15th of September 1830, George Stephenson’s Liverpool and Manchester Railway impacted society on every level. Railways were not a new idea, they have been about in one form or another since Ancient Grecian times.

By the 19th century, mineral railways were becoming common around coalfields in Yorkshire, the Northeast, and Wales, but they generally served the limited purpose of moving coal from mines to waterways.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the first to connect two major urban areas (Inter-City) and the first to have timetabled and ticketed passenger travel and the first to be powered by locomotives for the entire length of the passenger journey.

The Railway was the brainchild of Liverpool merchants, who were frustrated by difficulties in getting their goods from the Liverpool docks to the mills of Manchester. It was claimed that it took longer to get goods to Manchester than it took for them to arrive from the Americas.

The project was fiercely opposed by the landed gentry and the canal and road owners. It was kicked out of Parliament in 1825 before finally getting Royal Ascent in 1826. The 30 mile line spawned a 30,000 mile network by the end of the 19th century.

The success of this line can be best measured by the fact that it is still in daily use to this day.

Paul O’Donnell of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Trust explains the importance of the Railway. “It helps to understand what life was like before the railway.

Paul O’Donnell of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Trust explains the importance of the Railway. “It helps to understand what life was like before the railway.

On average, people lived their lives and died within seven miles of the place they were born. They had been tied to the local estates for work, but railways meant they could now travel to find better jobs, causing the decline of the landed gentry.

People in towns had to keep their own livestock, as it was almost impossible to get fresh produce any other way. The railway meant milk, eggs and meat could be freshly delivered from rural areas, along with cheaper coal.

People could start enjoying a more varied diet as fruits and vegetables from other regions could be transported further than ever before.

In 1841, Thomas Cook organised his first railway excursion, ushering in the unheard of concept of day trips and holidays.

In 1841, Thomas Cook organised his first railway excursion, ushering in the unheard of concept of day trips and holidays.

The railways even changed how we tell the time, as sundials were not sustainable for timetables as we needed it to be the same time in London as it was in Bristol or Liverpool.”

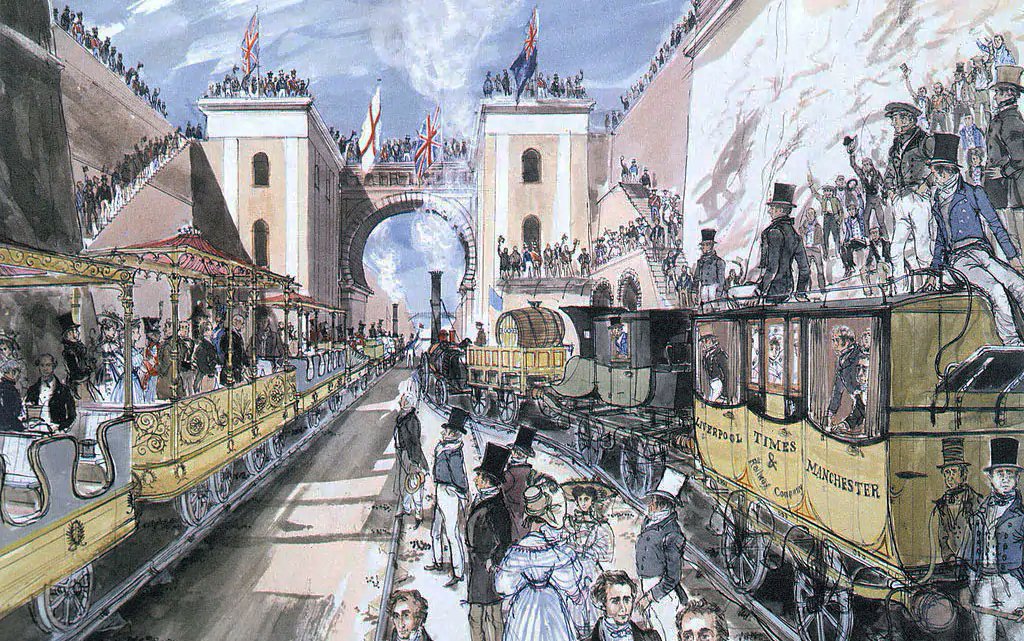

While the entire line is world-renowned, this cutting was the location of the opening ceremony, where the then Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington climbed into specially constructed carriages and travelled the line to Manchester and back.

The site was a unique and elegant solution for handling the rolling stock at the Liverpool end of the line. It connected the Liverpool station at Crown Street and the Wapping Tunnel and the waterfront docks with the main line to Manchester.

Carriages would freewheel down a small tunnel from the Crown Street passenger station entering the cutting where they would be connected to waiting locomotives to continue on to Manchester.

Upon their return, the locomotive would be disconnected, and the coaches would be pulled back up to Crown Street, initially by beasts of burden, and later by a rope system. Goods waggons would free-wheel down the Wapping Tunnel to the goods yard at Kings Dock.

Reloaded, they would be pulled up the tunnel via an impressive “endless rope” system which was powered by stationary steam engines hidden in the towers of the long gone Moorish Arch, which also acted as an impressive gateway to the terminus.

The Cutting becomes only the fifth Scheduled Monument in Liverpool, following Speke Hall’s buried moat, West Derby’s Mott and Baily castle, (neither of which have any visible remains) and the Calderstones and their satellite “Robin Hood” stone on Booker Avenue.

The cutting is the youngest and the most impressive of the group and it deserves to become a tourist attraction in the future, with Historic England even suggesting it could form part of a new World Heritage Site.

In the short term we would like to see the stakeholders come together and decide on what future the site can have. It is in desperate need of devegetation, which has already damaged parts of the original structure and may be doing untold damage to the buried “endless rope” system

It then needs a full archaeological investigation using modern techniques, given that the last investigation was fifty years ago and only exposed part of the site.

After that, it needs to be available to the public in some capacity

After that, it needs to be available to the public in some capacity

This again will need to be a decision for the stakeholders, but with the bicentenary of the railway rapidly approaching, this site deserves to be a key location for those celebrations.

The Trust would like to thank Historic England for their diligent investigation and report on the site and to all the other parties involved in the consultation, including Network Rail, the Railway Heritage Trust, the Newcomen Society, the Institute of Civil Engineers,

the Railway and Canal Historical Society, the Rainhill Railway and Heritage Society, and the Association for Industrial Archaeology amongst many others.

View the listing on Historic England’s website historicengland.org.uk/.../the.../lis…

View the listing on Historic England’s website historicengland.org.uk/.../the.../lis…

The link appears to be broken now. Go to the search feature and search for "1476078" which is the reference number.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh