1/

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll walk you through a framework that I call "Lindy vs Turkey".

This is a super-useful set of ideas for investors.

Time and again, these ideas have helped me think more clearly about the LONGEVITY of the companies in my portfolio.

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll walk you through a framework that I call "Lindy vs Turkey".

This is a super-useful set of ideas for investors.

Time and again, these ideas have helped me think more clearly about the LONGEVITY of the companies in my portfolio.

2/

Imagine we're buying shares in a company -- ABC Inc.

ABC is a very simple company. It earns $1 per share every year. These earnings don't grow over time.

And ABC returns all its earnings back to its owners -- by issuing a $1/share dividend at the end of each year.

Imagine we're buying shares in a company -- ABC Inc.

ABC is a very simple company. It earns $1 per share every year. These earnings don't grow over time.

And ABC returns all its earnings back to its owners -- by issuing a $1/share dividend at the end of each year.

3/

Suppose we buy ABC shares for $5 a share.

That's a P/E ratio of 5.

We know we get back $1/year as a dividend.

So, for us to NOT lose money, ABC should survive AT LEAST 5 more years.

If something happens and ABC DIES before then, we'll likely lose money.

Suppose we buy ABC shares for $5 a share.

That's a P/E ratio of 5.

We know we get back $1/year as a dividend.

So, for us to NOT lose money, ABC should survive AT LEAST 5 more years.

If something happens and ABC DIES before then, we'll likely lose money.

4/

What if we pay a more expensive price -- say, a 20 P/E -- for our ABC shares?

Well, then we're betting that ABC will survive (and pay us dividends!) for at least another 20 years.

The odds of this may be meaningfully LOWER than the odds of ABC surviving just 5 more years.

What if we pay a more expensive price -- say, a 20 P/E -- for our ABC shares?

Well, then we're betting that ABC will survive (and pay us dividends!) for at least another 20 years.

The odds of this may be meaningfully LOWER than the odds of ABC surviving just 5 more years.

5/

What if ABC is a GROWING company instead?

Let's say its earnings grow at 10% per year.

Of course, this growth may not come for FREE. ABC may have to re-invest a portion of its earnings back into itself each year -- just to get this growth.

What if ABC is a GROWING company instead?

Let's say its earnings grow at 10% per year.

Of course, this growth may not come for FREE. ABC may have to re-invest a portion of its earnings back into itself each year -- just to get this growth.

6/

Let's say ABC gets a healthy 25% ROIIC -- Return On Incremental Invested Capital.

That means, for every dollar of additional earnings, the business needs $4 of additional capital invested into it.

Let's say ABC gets a healthy 25% ROIIC -- Return On Incremental Invested Capital.

That means, for every dollar of additional earnings, the business needs $4 of additional capital invested into it.

7/

So, to grow 10% next year -- from $1 to $1.10 of earnings per share -- the business will need an additional $0.40 per share invested into it.

If we assume this $0.40/share comes out of this year's earnings, that leaves $0.60/share that can be dividended out to owners.

So, to grow 10% next year -- from $1 to $1.10 of earnings per share -- the business will need an additional $0.40 per share invested into it.

If we assume this $0.40/share comes out of this year's earnings, that leaves $0.60/share that can be dividended out to owners.

8/

So, here's how this plays out.

Each year, ABC returns 60% of its earnings back to owners -- via a dividend.

The other 40% is retained and re-invested back into the business. This helps GROW earnings (and *future* dividends) at 10% per year -- for an ROIIC of 25%.

So, here's how this plays out.

Each year, ABC returns 60% of its earnings back to owners -- via a dividend.

The other 40% is retained and re-invested back into the business. This helps GROW earnings (and *future* dividends) at 10% per year -- for an ROIIC of 25%.

9/

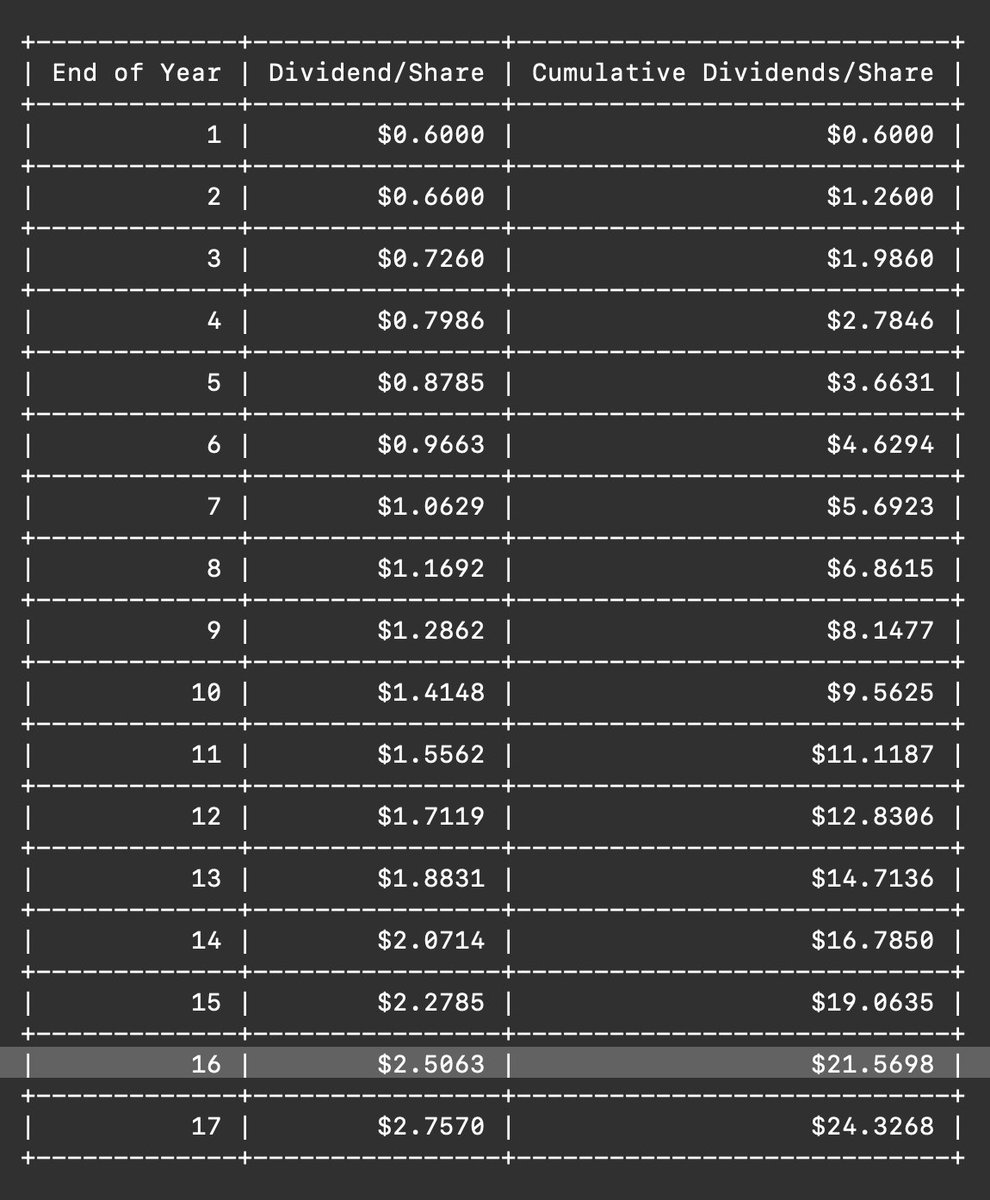

So, we have:

Year 1 Dividend: $0.60/share,

Year 2 Dividend: $0.60 * 1.1 = $0.66/share,

Year 3 Dividend: $0.66 * 1.1 = $0.726/share,

And so on.

So, we have:

Year 1 Dividend: $0.60/share,

Year 2 Dividend: $0.60 * 1.1 = $0.66/share,

Year 3 Dividend: $0.66 * 1.1 = $0.726/share,

And so on.

10/

Suppose we pay 20 times current earnings -- ie, $20/share -- for ABC.

At what point will our cumulative dividends exceed our purchase price?

A simple simulation shows that this will happen after 11 years.

Suppose we pay 20 times current earnings -- ie, $20/share -- for ABC.

At what point will our cumulative dividends exceed our purchase price?

A simple simulation shows that this will happen after 11 years.

11/

So, if we buy a "no growth" company at 20 times earnings, the company has to survive at least 20 years for us to recoup our investment.

But if we buy a "10% grower" (with 25% ROIIC) at the SAME 20 times earnings, it's enough if the company survives just 11 years.

So, if we buy a "no growth" company at 20 times earnings, the company has to survive at least 20 years for us to recoup our investment.

But if we buy a "10% grower" (with 25% ROIIC) at the SAME 20 times earnings, it's enough if the company survives just 11 years.

12/

Thus, whenever we buy a company for our portfolio (with the intention of holding it for the long term), we're making an *implicit bet* about the company's LONGEVITY.

- How long the company will survive,

- How long it will continue growing and paying us dividends, etc.

Thus, whenever we buy a company for our portfolio (with the intention of holding it for the long term), we're making an *implicit bet* about the company's LONGEVITY.

- How long the company will survive,

- How long it will continue growing and paying us dividends, etc.

13/

Capitalism is brutal. Companies die all the time.

So, if we're paying up for a company, we should be reasonably sure about its LONGEVITY.

As investors, we need to cultivate the ability to identify companies that will stick around and stay strong for years and years.

Capitalism is brutal. Companies die all the time.

So, if we're paying up for a company, we should be reasonably sure about its LONGEVITY.

As investors, we need to cultivate the ability to identify companies that will stick around and stay strong for years and years.

14/

This is where great investors like Warren Buffett shine.

Many of Buffett's greatest investments -- American Express, Coca Cola, See's Candies, BNSF -- are SUPER long lived.

Year after year, decade after decade -- they put cash into Buffett's pocket.

This is where great investors like Warren Buffett shine.

Many of Buffett's greatest investments -- American Express, Coca Cola, See's Candies, BNSF -- are SUPER long lived.

Year after year, decade after decade -- they put cash into Buffett's pocket.

15/

So, how do we assess a business's longevity?

For this, I very much like the "Lindy Effect" concept.

This is the idea that things that have *already* stood the test of time -- by surviving/thriving for many years up to today -- are also pretty likely to survive in FUTURE.

So, how do we assess a business's longevity?

For this, I very much like the "Lindy Effect" concept.

This is the idea that things that have *already* stood the test of time -- by surviving/thriving for many years up to today -- are also pretty likely to survive in FUTURE.

16/

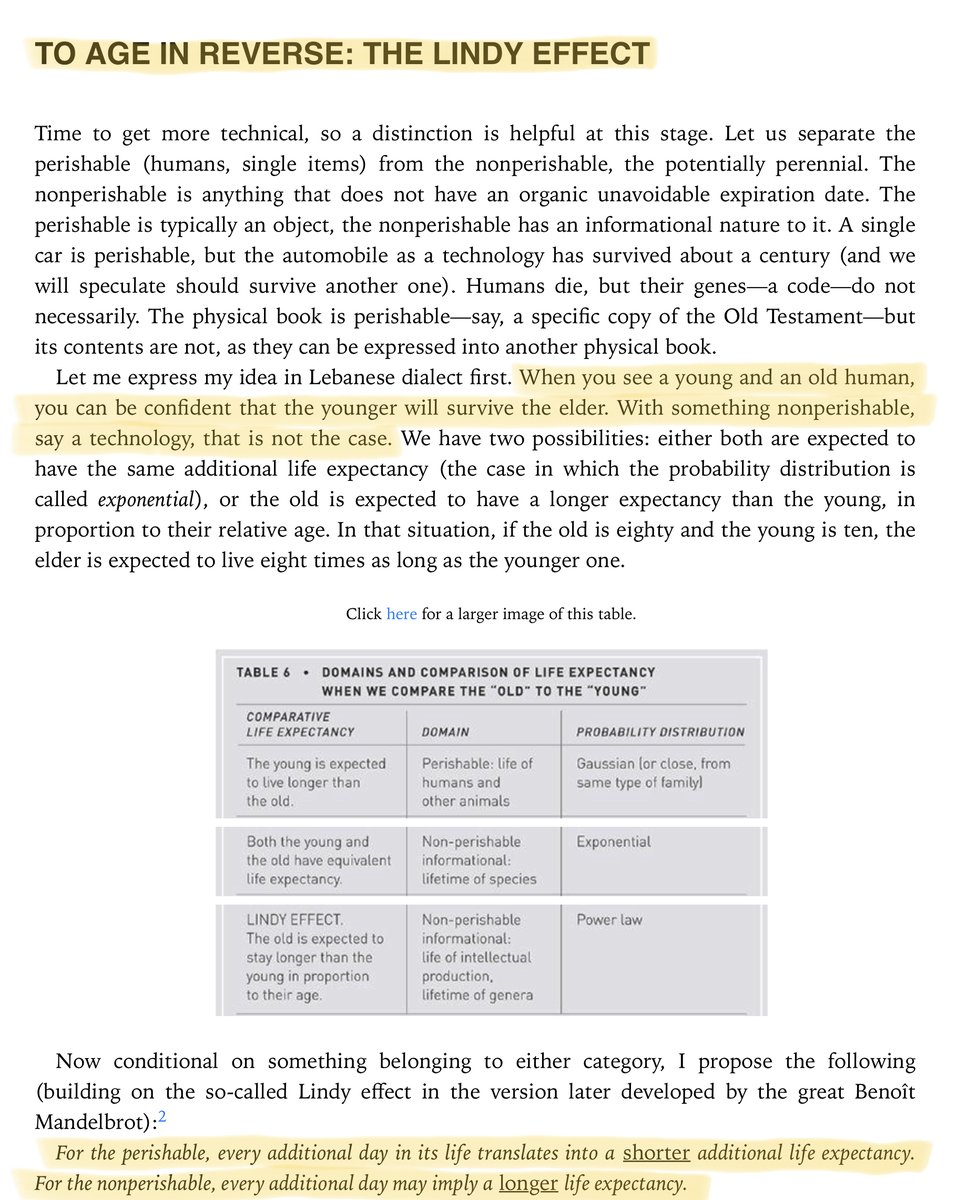

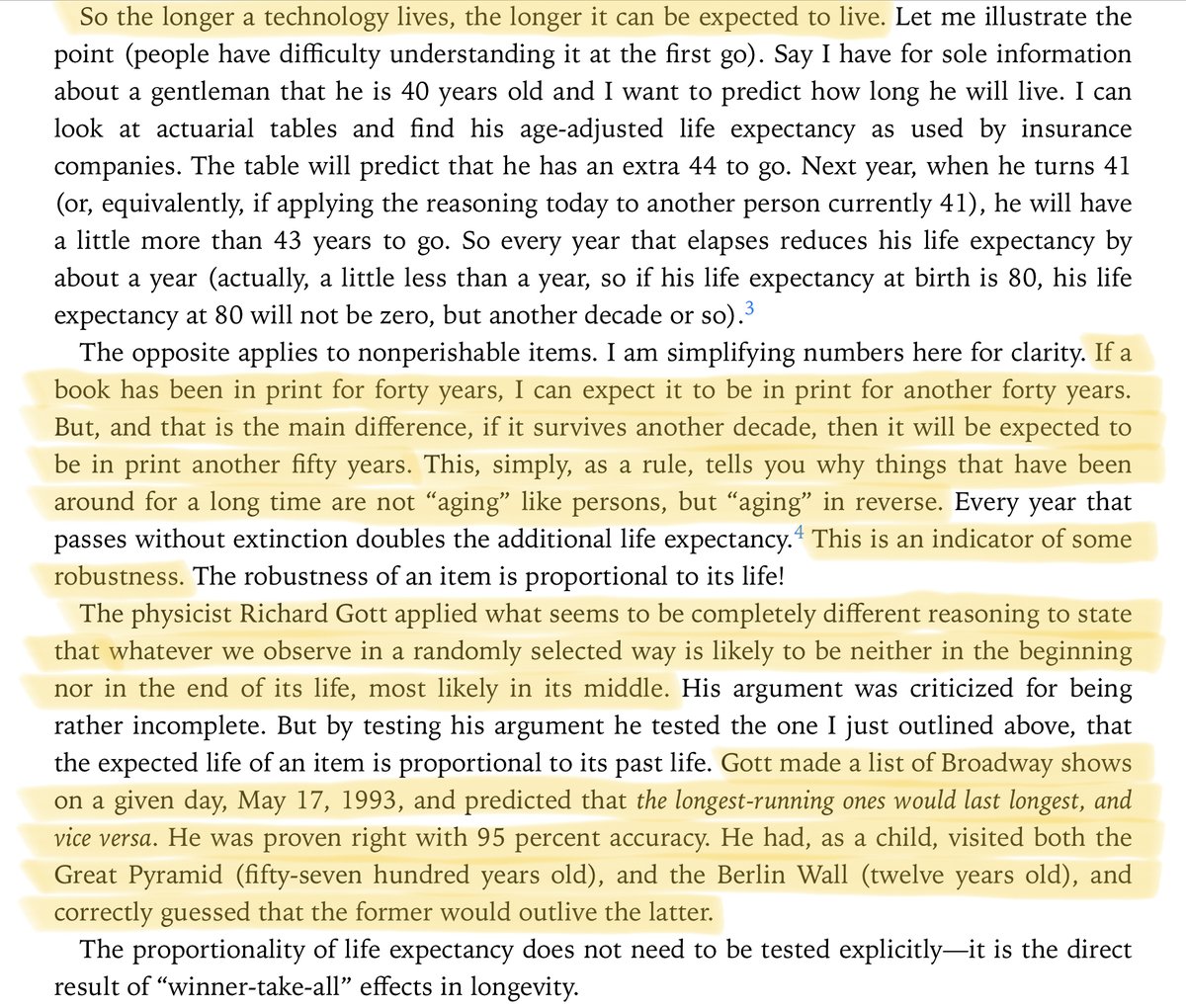

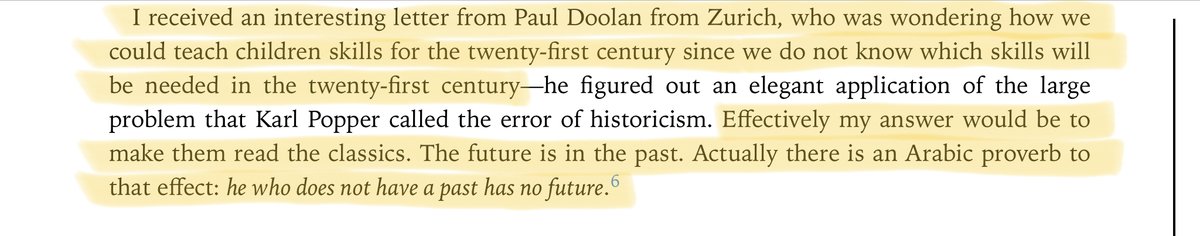

For example, if something has survived for 50 years, there's a good chance it'll survive *another* 50 years.

This idea was popularized by Nassim Taleb (@nntaleb) in his book Antifragile:

For example, if something has survived for 50 years, there's a good chance it'll survive *another* 50 years.

This idea was popularized by Nassim Taleb (@nntaleb) in his book Antifragile:

17/

This "Lindy" idea makes intuitive sense.

The very fact that something has survived a long time may be an indication that this thing has some built-in strength.

Some immunity against the vicissitudes of life.

And that immunity may continue into the future.

This "Lindy" idea makes intuitive sense.

The very fact that something has survived a long time may be an indication that this thing has some built-in strength.

Some immunity against the vicissitudes of life.

And that immunity may continue into the future.

18/

For example, many countries in the world suffer from high infant mortality.

An uncomfortably large fraction (like 4%) of kids in these countries die before they turn 1 year old.

But a much *smaller* fraction of 5-year olds die before they turn 6.

For example, many countries in the world suffer from high infant mortality.

An uncomfortably large fraction (like 4%) of kids in these countries die before they turn 1 year old.

But a much *smaller* fraction of 5-year olds die before they turn 6.

19/

Why? Because the very fact that a kid has survived up to age 5 is an indicator of good health -- absence of birth defects, decent immunity against diseases and infections, etc.

And such kids are likely to *continue* surviving -- to eventually become healthy adults.

Why? Because the very fact that a kid has survived up to age 5 is an indicator of good health -- absence of birth defects, decent immunity against diseases and infections, etc.

And such kids are likely to *continue* surviving -- to eventually become healthy adults.

20/

Similar logic may apply to businesses.

A large fraction of businesses die in their first year.

But businesses that have overcome those odds -- and that have managed to survive for a long time -- probably have *something* going for them.

Some "moat".

Similar logic may apply to businesses.

A large fraction of businesses die in their first year.

But businesses that have overcome those odds -- and that have managed to survive for a long time -- probably have *something* going for them.

Some "moat".

21/

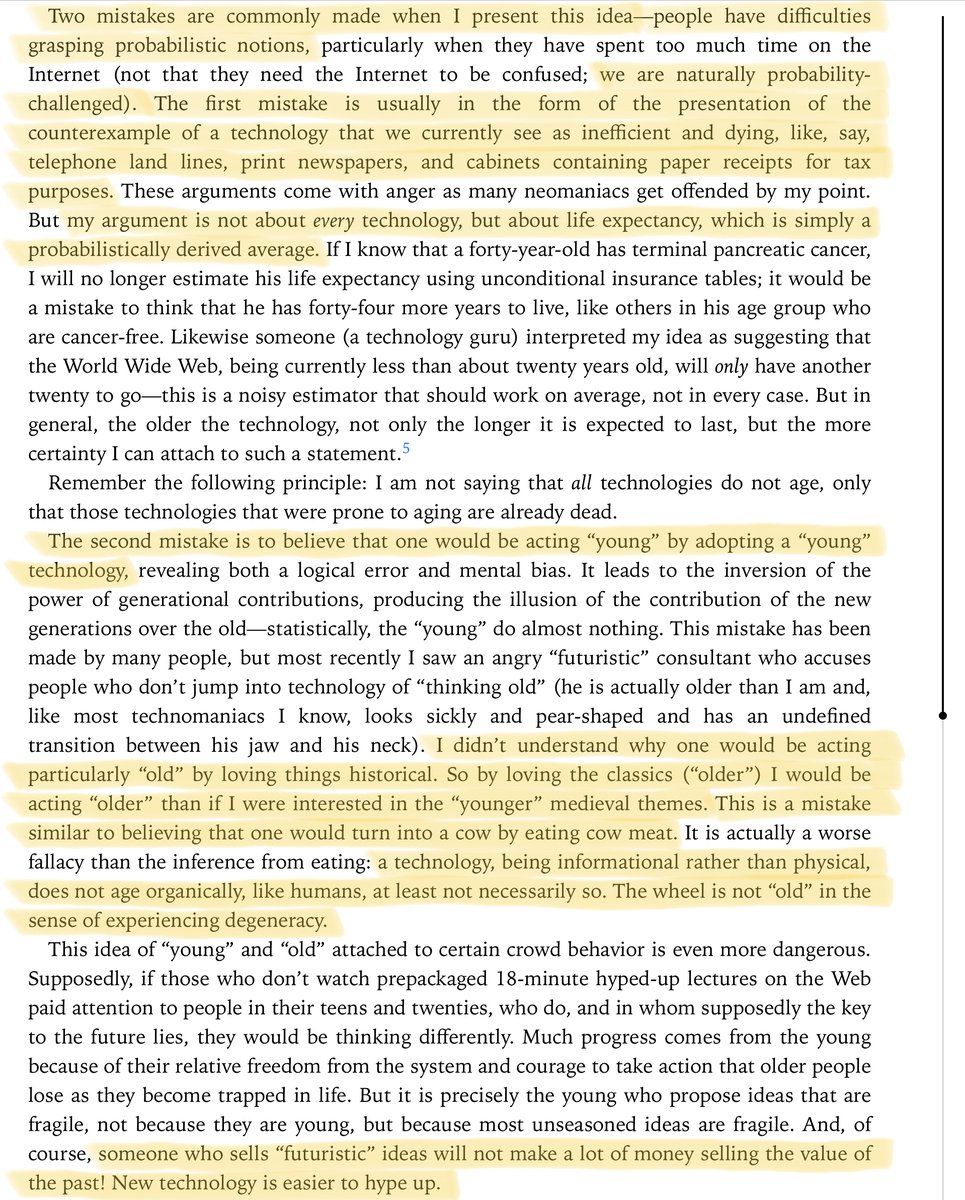

But here's what makes investing difficult.

NOT everything is Lindy.

Some businesses may have survived a long time.

But it may not be because they're "strong" or "durable".

It may simply be due to *dumb luck*.

Such businesses are NOT "Lindys".

They are "Turkeys".

But here's what makes investing difficult.

NOT everything is Lindy.

Some businesses may have survived a long time.

But it may not be because they're "strong" or "durable".

It may simply be due to *dumb luck*.

Such businesses are NOT "Lindys".

They are "Turkeys".

22/

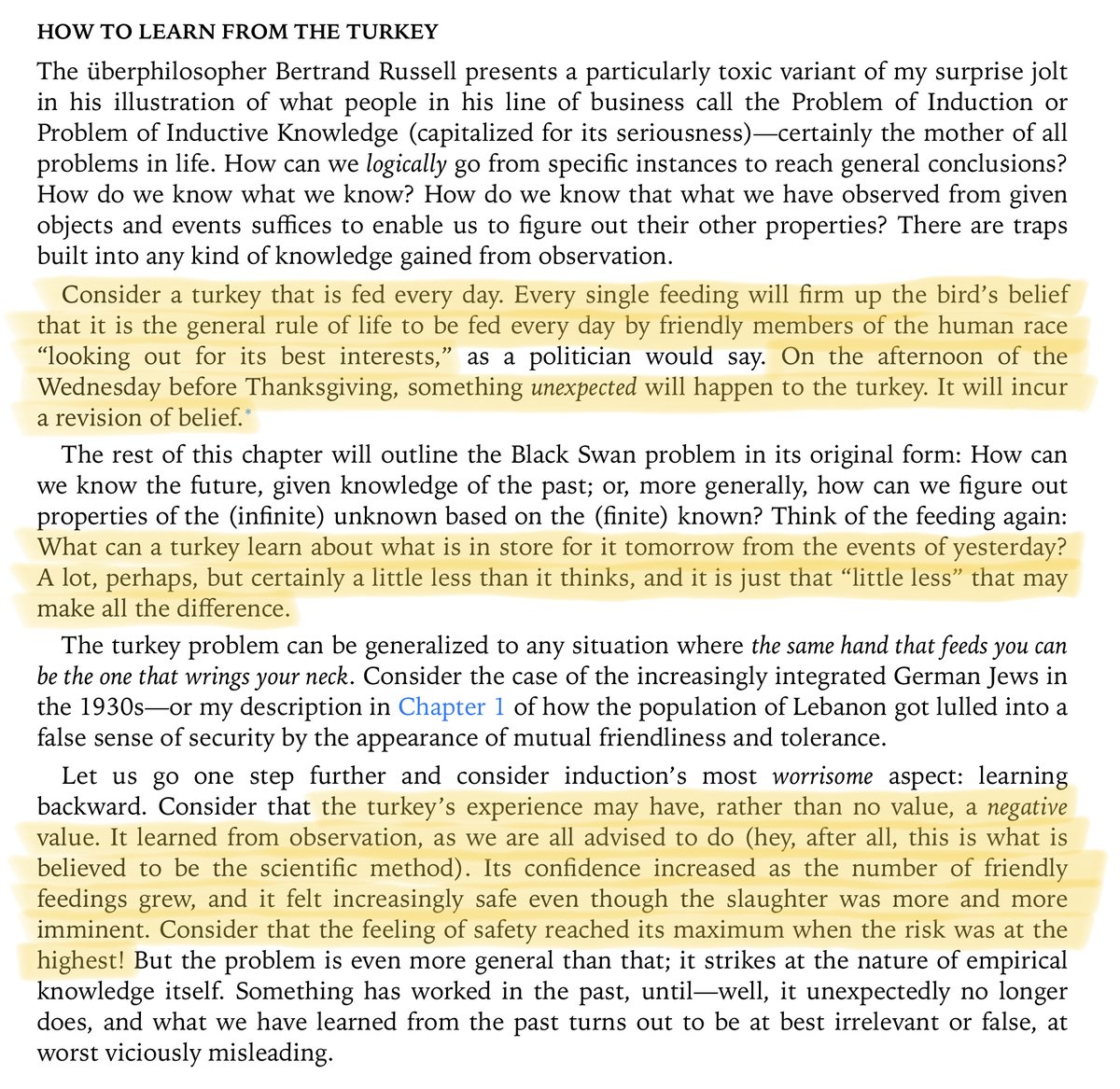

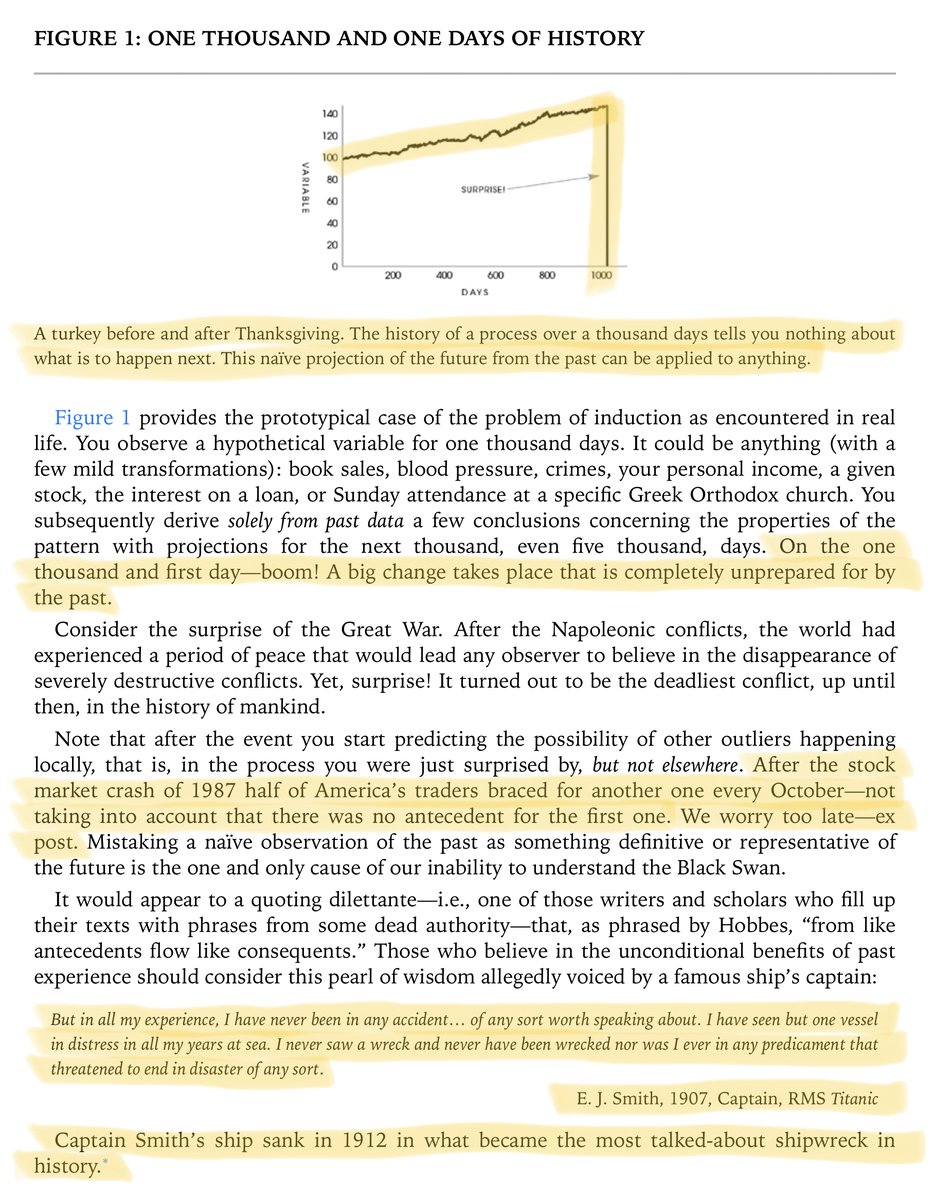

This "Turkey" idea is also Taleb's.

In his book The Black Swan, Taleb imagines the life of a Thanksgiving turkey.

The turkey's life starts off wonderful. It survives and thrives day after day -- for 364 days.

Until Thanksgiving day, when it's slaughtered.

(h/t @nntaleb)

This "Turkey" idea is also Taleb's.

In his book The Black Swan, Taleb imagines the life of a Thanksgiving turkey.

The turkey's life starts off wonderful. It survives and thrives day after day -- for 364 days.

Until Thanksgiving day, when it's slaughtered.

(h/t @nntaleb)

23/

In a similar way:

Just because a business has done well for a few years does NOT mean it has durable competitive advantages.

The business may have just gotten lucky.

It may be a Turkey about to be slaughtered, NOT a Lindy that will print cash for years to come.

In a similar way:

Just because a business has done well for a few years does NOT mean it has durable competitive advantages.

The business may have just gotten lucky.

It may be a Turkey about to be slaughtered, NOT a Lindy that will print cash for years to come.

24/

So, how do we distinguish Lindys from Turkeys in the business world?

I think the key distinction is this:

With each passing year, Lindys get *harder and harder* to kill. They keep improving their competitive position.

Every year that doesn't kill them makes them stronger.

So, how do we distinguish Lindys from Turkeys in the business world?

I think the key distinction is this:

With each passing year, Lindys get *harder and harder* to kill. They keep improving their competitive position.

Every year that doesn't kill them makes them stronger.

25/

By contrast, a Thanksgiving turkey is more or less just as easy to kill on day 365 as it was on day 1.

Turkeys don't really become more resilient or harder to kill over time. They just push their luck for as long as it lasts.

By contrast, a Thanksgiving turkey is more or less just as easy to kill on day 365 as it was on day 1.

Turkeys don't really become more resilient or harder to kill over time. They just push their luck for as long as it lasts.

26/

So, when we analyze a business, I think we should look for evidence that the business is building strength -- becoming harder and harder to kill -- over time.

For example, I like businesses whose products are becoming more and more "sticky" over time.

So, when we analyze a business, I think we should look for evidence that the business is building strength -- becoming harder and harder to kill -- over time.

For example, I like businesses whose products are becoming more and more "sticky" over time.

27/

Take Apple for instance.

Today, I am much more reliant on Apple's devices, services, and apps -- than I was 5 years ago.

I use the Apple "ecosystem" for reading, note-taking, music, messaging, email, and so much more!

If there are enough people like me, Apple is Lindy.

Take Apple for instance.

Today, I am much more reliant on Apple's devices, services, and apps -- than I was 5 years ago.

I use the Apple "ecosystem" for reading, note-taking, music, messaging, email, and so much more!

If there are enough people like me, Apple is Lindy.

28/

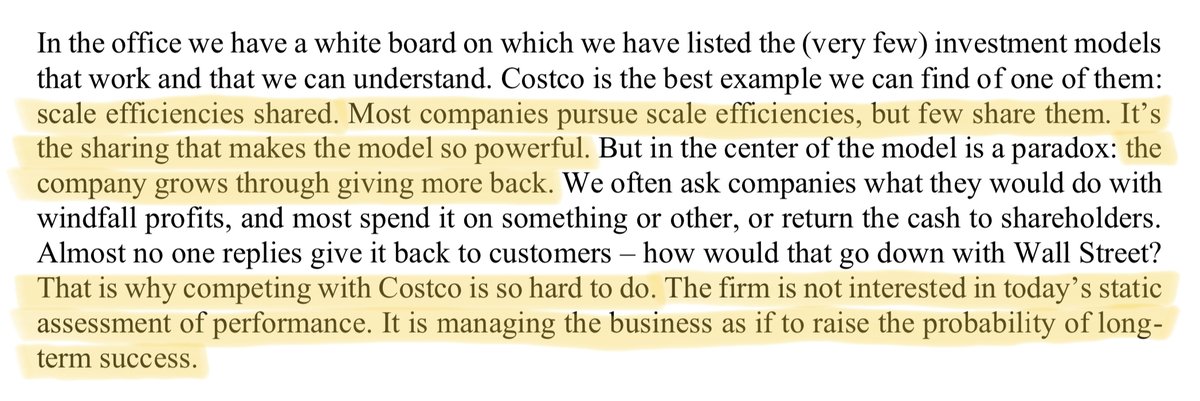

Another category of Lindy companies are those with "scale economics shared".

These companies are able to use their growing scale to drive down costs and continuously improve their customers' experience.

This makes it hard for an upstart without scale to kill them.

Another category of Lindy companies are those with "scale economics shared".

These companies are able to use their growing scale to drive down costs and continuously improve their customers' experience.

This makes it hard for an upstart without scale to kill them.

29/

For example, here's a snippet from Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria's Nomad Partnership letters -- describing how this model works for Costco:

(Link to ~218 page PDF: igyfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/upl…)

For example, here's a snippet from Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria's Nomad Partnership letters -- describing how this model works for Costco:

(Link to ~218 page PDF: igyfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/upl…)

30/

There are several other economic characteristics that can give a company powerful advantages and help make it Lindy.

To learn more about such qualities, please consider signing up for this course I'm teaching with Ali Ladha (@AliTheCFO):

maven.com/good-business-…

There are several other economic characteristics that can give a company powerful advantages and help make it Lindy.

To learn more about such qualities, please consider signing up for this course I'm teaching with Ali Ladha (@AliTheCFO):

maven.com/good-business-…

31/

If you're still with me, thank you very much!

As long term investors, we want to buy businesses that will keep giving us cash for a long long time.

I hope the "Lindy vs Turkey" framework helps you find such long-lived businesses.

Take care, and enjoy your weekend!

/End

If you're still with me, thank you very much!

As long term investors, we want to buy businesses that will keep giving us cash for a long long time.

I hope the "Lindy vs Turkey" framework helps you find such long-lived businesses.

Take care, and enjoy your weekend!

/End

*** ERROR ***

Folks, I made a mistake in Tweet 10 above.

In the "10% growth, 25% ROIIC" scenario, it will take us 16 (not 11) years to recoup our $20/share purchase price.

My apologies for the error. Thankfully, it doesn't invalidate the rest of the thread.

Folks, I made a mistake in Tweet 10 above.

In the "10% growth, 25% ROIIC" scenario, it will take us 16 (not 11) years to recoup our $20/share purchase price.

My apologies for the error. Thankfully, it doesn't invalidate the rest of the thread.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh