@BretDevereaux In his response to @Noahpinion Bret takes a swipe in passing at my work. It is not clear to what he refers ("effort to find support for this hypothesis in the ancient world"), as my my main effort for empirically testing this hypotheses has centered on the US from 1789 to ...

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion ... the present. With a huge emphasis on the contemporary America (from the 1970s on). Perhaps America in the late 20 century is an ancient country? The main source is Ages of Discord

peterturchin.com/ages-of-discor…

peterturchin.com/ages-of-discor…

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion I also stuck my neck out and made a scientific prediction in 2010, which unfortunately was borne out by reality

journals.plos.org/plosone/articl…

journals.plos.org/plosone/articl…

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion Cliodynamics colleagues and myself have also applied theory to other contemporary societies, as well as many historical ones. So I would say that the elite overproduction thesis has fared quite well in empirical tests, and dismissing it in passing is not good scholarship.

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion At the same time, there is much in Bret's blog post that I agree with. There are multiple epistemologies, and I quite appreciate what historians do, and I am very supportive of History as a mature discipline. My work is often misinterpreted as an attack on History, ...

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion ... but nothing could be further from truth. See here:

peterturchin.com/cliodynamica/t…

peterturchin.com/cliodynamica/t…

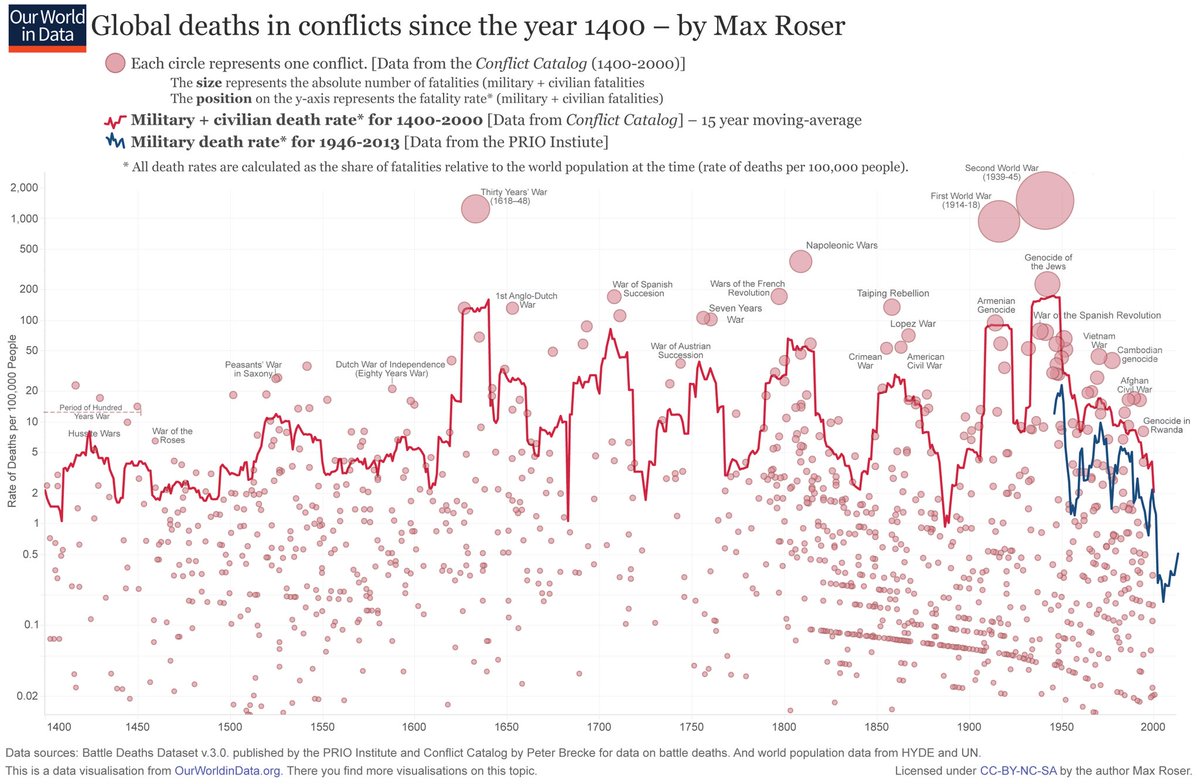

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion I also agree with Bret about his critique of Max Roser's "data" which is indeed "not charting global deaths in conflict, but rather in charting the rate at which evidence for battles is preserved over time"

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion However, this doesn't mean that such data are useless; to properly extract insights from them we need to include the measurement process in the analysis. This takes thought and work, but is a better alternative than just throwing up arms in defeat.

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion Returning to the main theme of Noah's post, I see value in both the work that historians do (which is not science) and the need to empirically test theories (which is science). The latter is the task for Cliodynamics. There is no need for the same researchers do both.

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion I also want to return to my first encounter with Bret's critique, which was of the Seshat project's first attempt to test the Big God theory. That was admittedly flawed, but we didn't give up -- we redesigned data collection, gathered more and better buttressed data, ...

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion ... and used better analysis methods. The result was published in June in a special feature in Religion, Brain, and Behavior, together with 7 commentaries, our response, and a retrospective:

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion I would be interested in Bret's comment/critique of that. I think that this effort, although by no means the final word, moves us a long way towards testing (and rejecting) evolutionary theories about the role of religion in the rise of complex human societies.

@BretDevereaux @Noahpinion Finally, Noah calls for empirical tests of theories in history. I'd like to attract his attention (and everybody else) to #Seshat project's massive effort to test 17 different theories about the evolution of social complexity across the past 10,000 years:

science.org/doi/10.1126/sc…

science.org/doi/10.1126/sc…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh