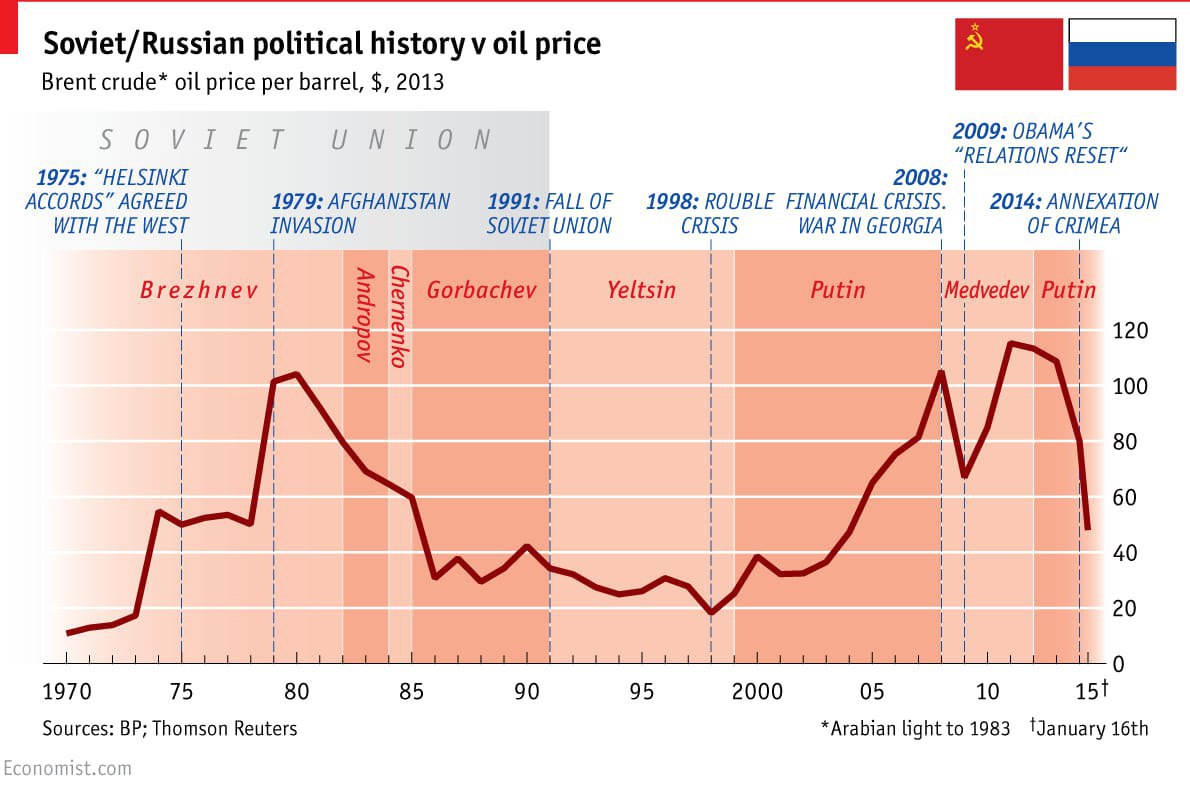

Now we associate Gorbachev with Perestroika, which in its turn is interpreted as nice Gorbachev being nice. In reality, in the beginning of his rule Gorbachev continued Andropov's Neo-Stalinist policies. But then the oil price dropped and didn't bounce back. Hence, Perestroika🧵

Brezhnev's era is usually referred to as Застой, the Stagnation. If Khrushchev unironically aimed to build Communism, Brezhnev dropped any attempts to do so. High oil prices of the 1970s created illusion of prosperity, while in reality system was becoming less and less efficient

Khruchev saw Communism as a realistic goal. He even set a specific deadline - 1980. Brezhnev however, cut all the specific deadlines from the Party program. Future oriented paradigm (building Communism) died and the new, past-oriented one emerged. Worshipping the Great Victory

Even though the Victory-worshipping took its most absurd forms under Putin, it originated under Brezhnev. Since the country was not oriented to the future anymore, it was now oriented to the past. Propaganda accents were gradually shifted from the October Revolution to the WWII

The KGB Chief Andropov who accumulated the immense power under Brezhnev was critical of where the system was going. KGB created a number of formal and informal economic think tanks working on how to overcome the crisis. Many future radical reformers of the 1990s originated there

Upon succeeding Brezhnev, Andropov tried to reinvigorate the USSR. He started a crusade against corruption, all forms of private commerce & business, and idleness. KGB was literally doing raids in cinemas or in stores at the daytime, catching those who were supposed to be at work

Andropov also did a number of cadre changes, promoting younger officials to fight with established gerontocracy. And Gorbachev was probably his favourite, since the 1960s. He tried to lobby him into the higher echelons of power, first unsuccessfully

In 1978 Andropov had a chance. A Central Committee secretary for agriculture died, so they had a vacancy. Andropov organised what would be later called "A meeting of four General Secretaries": Brezhev, Andropov, Chernenko and Gorbachev. Brezhnev accepted Gorbachev's candidature

Gorbachev's career was incredible and breaking all the established rules. In 1978 he becomes a Central Committee Secretary. In 1980 a Politburo member. He was not even 60 then, only 59 years old! Absolutely incredible.

In the late Soviet gerontocracy, Gorbachev was a Boss Baby

In the late Soviet gerontocracy, Gorbachev was a Boss Baby

The Boss Baby promoted thanks to Andropov's patronage outlived his superiors. In the 1980s Soviet leaders started dying one by one (=gun-carriage races)

1981 - 75 y.o. Brezhnev

1984 - 64 y.o. Andropov

1985 - 73 y.o Chernenko

Baby Boss outlived them all and succeeded the throne

1981 - 75 y.o. Brezhnev

1984 - 64 y.o. Andropov

1985 - 73 y.o Chernenko

Baby Boss outlived them all and succeeded the throne

Upon inheriting the throne, Gorbachev largely continued Andropov's policies:

1) Neo-Stalinist politics

2) Strong industrial policy

3) Technological import from the West

He didn't aim to liberalise the system. To the contrary, he aimed to harden and reinvigorate it

1) Neo-Stalinist politics

2) Strong industrial policy

3) Technological import from the West

He didn't aim to liberalise the system. To the contrary, he aimed to harden and reinvigorate it

Agenda of the 27th Party Congress, held in February 1986 was Neo-Stalinist. Under early Gorbachev, Soviet repressions against any form of private enterprises peaked. In May 1986 they issued an order:

"On measures to increase the struggle against the unearned incomes"

"On measures to increase the struggle against the unearned incomes"

To put it simply, only your salary from the state was the "earned" income. All your private hustles were unearned and had to be uprooted. A wave of repressions against all forms of private businesses followed. Small repairment shops or workshops were closed en masse

Rural population suffered, too. Private hothouses, livestock barns were destroyed en masse. You obviously don't need this hothouse for yourself, it looks like you are *selling* what you grow. That's unearned income. Markets on which one could sell the harvest were closed, too

Let me give you an example. Soviet law made a distinction between legal "personal property" (for your own needs) and illegal "private property" (means of production)

So if you rode you car, that's ok. But if you are doing taxi service, it becomes means of production = illegal

So if you rode you car, that's ok. But if you are doing taxi service, it becomes means of production = illegal

In early Gorbachev's era policemen would ambush drivers who were suspected of taking passengers for money. If you act as a taxi, you use you car as the means of production to get the unearned income. Only what you get from the state is earned, any other hustle is a crime

Draconian measures against private entrepreneurship, commerce, etc. were combined with the strong industrial policy. Gorbachev aimed for a new Industrialisation, now with a specific focus on machinery and IT, but totally controlled by the state

See cia.gov/readingroom/do…

They planned "technological renovation", aiming to renew the 1/3 of Soviet industry by the 1990s. They planned to increase investments in the machinery by 80%. They also put a special focus on computers and automation. All under the state control

They planned "technological renovation", aiming to renew the 1/3 of Soviet industry by the 1990s. They planned to increase investments in the machinery by 80%. They also put a special focus on computers and automation. All under the state control

Early Gorbachev =/= "liberal"

Early Gorbachev = suppress the private sector + pursue a statist industrialisation project with the focus on complex machinery and IT at the cost of the mass suffering. They knew very well that consumption standards gonna drop and planned for it

Early Gorbachev = suppress the private sector + pursue a statist industrialisation project with the focus on complex machinery and IT at the cost of the mass suffering. They knew very well that consumption standards gonna drop and planned for it

Crusade on the private business should be regarded in the context of industrial policy. If we plan to invest all the money into industry and drop the consumption, lots of people may say fuck it and just switch to side hustles: hothouse, taxi service, workshop. Don't allow them to

Soviet/Russian anti-business policies were not "madness" as so many presume. They were absolutely rational. Destroy 100% of the private sector, so people would have no other choice but to sell their labour to the state. That allows to keep the real salaries as low as possible

Neither in Soviet Union, nor in Russia low salaries are natural. In both cases, it is the deliberate policy of the state to minimise the cost of labor. In modern Russian (provincial) employers are often punished for paying too much. Gonna elaborate this later

In the early 1986 Gorbachev pursued a Neo-Stalinist policy of suppressing the private sector, reducing consumption and investing it all into the state-owned industry. Much like Stalin did, like Andropov aimed, but did not have a chance to

By the late 1986. the USSR did the U-tun

By the late 1986. the USSR did the U-tun

U-turn of 1986

May 1986 - "On measures to increase the struggle agains the unearned incomes". Extremely statist and anti-market

November 1986 - "Law on Individual Labour Activity". Basically people not obliged to work for the state can do private hustles. Extremely pro-market

May 1986 - "On measures to increase the struggle agains the unearned incomes". Extremely statist and anti-market

November 1986 - "Law on Individual Labour Activity". Basically people not obliged to work for the state can do private hustles. Extremely pro-market

If in the early 1986, Gorbachev pursued Neo-Stalinist statist projects, by the late 1986 he did an U-turn and switched to the pro-market policies that only deepened and accelerated till the end of his rule. What did motivate this sudden and unexpected U-turn?

In 1986 oil prices crashed and didn't bounce back. The USSR could not fund the increase in technological import anymore, thus all the Gorbachev's plans for "technological renovation" went to the bin and his industrial policy, too. Thus he did a U-turn towards liberalism. The end

PS When discussing Soviet/Russian policies we tend to focus on irrelevant crap, like which ruler is "liberal"/"democratic" (no one). But the oil prices are a much more important factor behind Kremlin's policy.

Expensive oil -> Aggressive

Cheap oil -> Docile

Now it's expensive

Expensive oil -> Aggressive

Cheap oil -> Docile

Now it's expensive

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh