I wrote about career advice.

Recently, I've been struck by how much online career advice is overly personal (do these 3 things I did) or political (all hard work is a capitalist con).

So I wrote down 5 ideas that've made the biggest impression on me.

theatlantic.com/newsletters/ar…

Recently, I've been struck by how much online career advice is overly personal (do these 3 things I did) or political (all hard work is a capitalist con).

So I wrote down 5 ideas that've made the biggest impression on me.

theatlantic.com/newsletters/ar…

1) "Don't take the job you want to *tell* people you do. Take the job you want to do."

@JamesFallows told me this circa 2013. I've never forgotten it. It's the chestnut I've repeated to more people than any other piece of work advice I've ever received.

@JamesFallows told me this circa 2013. I've never forgotten it. It's the chestnut I've repeated to more people than any other piece of work advice I've ever received.

2) On a similar theme of "work is mostly about time":

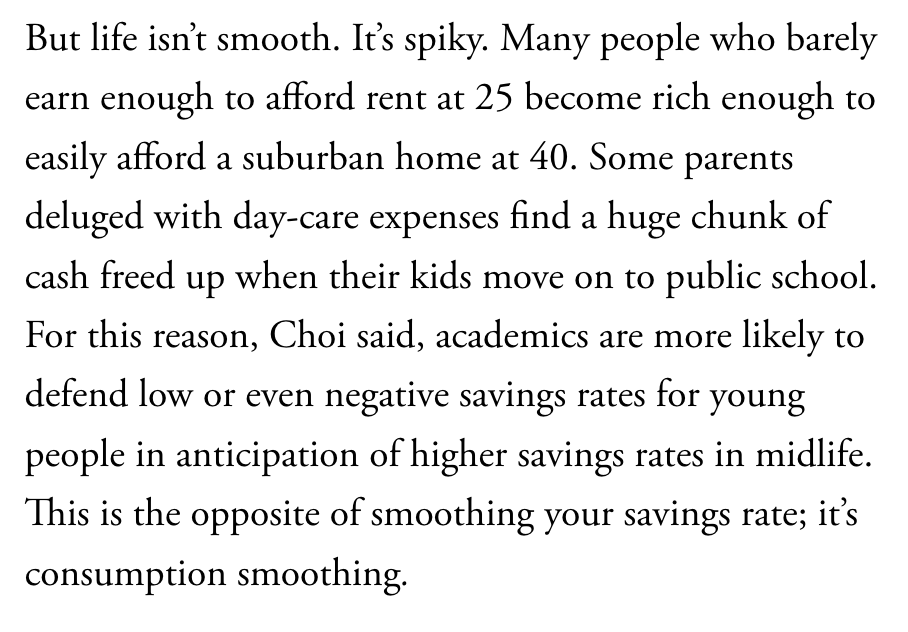

Life is roughly 4,000 weeks long. Your career is 80,000 hours, or, sequentially, roughly 500 total lived weeks; or one-eighth of life. That's too big a thing to not take seriously and too small to take too seriously.

Life is roughly 4,000 weeks long. Your career is 80,000 hours, or, sequentially, roughly 500 total lived weeks; or one-eighth of life. That's too big a thing to not take seriously and too small to take too seriously.

3) Explore, then exploit.

The paper that's made the biggest impression on my attitude toward work & creativity is Dashun Wang's on the explore-exploit sequence. I'm a huge proponent of role-switching to find the unique combo of skills that you can synthesize and specialize in.

The paper that's made the biggest impression on my attitude toward work & creativity is Dashun Wang's on the explore-exploit sequence. I'm a huge proponent of role-switching to find the unique combo of skills that you can synthesize and specialize in.

4) People should be more honest with themselves about how much professional success matters to them.

I don't think career ambition is a universal virtue. It's more like a taste that varies among people. That's okay. If it's your taste, own it without judgment or self-deception.

I don't think career ambition is a universal virtue. It's more like a taste that varies among people. That's okay. If it's your taste, own it without judgment or self-deception.

5) Flow, via the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, is probably the most true concept in the field of work psychology.

We feel happiest when our “body or mind is stretched to its limits in a VOLUNTARY effort to accomplish something DIFFICULT and WORTHWHILE.”

We feel happiest when our “body or mind is stretched to its limits in a VOLUNTARY effort to accomplish something DIFFICULT and WORTHWHILE.”

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh