1. This 🧵, I want to devote to some remarkable examples of Sabbatianism in R’ Yehiel Michel b. Abraham Epstein (d. around 1706)'s extremely popular קיצור של״ה that goes well beyond the comments of Emden or published scholarship on the topic

It gets really 🤯🤯🤯

It gets really 🤯🤯🤯

2. PSA if you want some background on what this is all about check this out:

https://twitter.com/yonibrander/status/1569818360946331648

3. The first thing to say about the Kitzur Shelah is that in essential ways, it is not a Kitzur of anything nor is it mainly the Shelah.

[Cue the classic Voltaire line turned SNL routine about the Holy Roman Empire]

[Cue the classic Voltaire line turned SNL routine about the Holy Roman Empire]

3. True, the actual Shnei Luchot ha-Brit features in the work.

But many people have wrongly assumed it was mostly a compendium.

In truth, much of the book’s contents are either sources that Epstein collected or selections that he wrote by himself.

But many people have wrongly assumed it was mostly a compendium.

In truth, much of the book’s contents are either sources that Epstein collected or selections that he wrote by himself.

4. Second, the Kitzur Shelah was immensely popular in the 18th century and beyond.

Epstein’s work, first published in the 1690s, appealed to the masses, not just other rabbinic elites.

Epstein’s work, first published in the 1690s, appealed to the masses, not just other rabbinic elites.

5. He included sections that he translated into Yiddish so everyday folks could understand them.

6. S. Noble claimed that this was because he was a proto-Yiddishist.

I disagree. It was more about reaching a mass of people and influencing them. That is why he translates things like long Viddui, it isn't about Yiddish- it is about understanding one's confession for Teshuva.

I disagree. It was more about reaching a mass of people and influencing them. That is why he translates things like long Viddui, it isn't about Yiddish- it is about understanding one's confession for Teshuva.

7. And in the mid-1700s, someone translated a digest of the Kitzur Shelah translated into Yiddish as Etz Chaim.

This had maybe had more Yiddishist vibes, but it also speaks to the fact the book was accessible and popular by that point.

This had maybe had more Yiddishist vibes, but it also speaks to the fact the book was accessible and popular by that point.

8. Indeed, it was super popular.

Beit Eked Seforim counts some 18 editions of the Yiddish version & nearly 30 (!!!) of the Hebrew Kitzur Shelah before the turn of the 20th century.

And there have been several more since that time.

Beit Eked Seforim counts some 18 editions of the Yiddish version & nearly 30 (!!!) of the Hebrew Kitzur Shelah before the turn of the 20th century.

And there have been several more since that time.

9. The Kitzur Shelah was also a popular guide for essential Jewish practice in the 18th and 19th centuries.

A quick scan of Responsa Project or Otzar will show not all Poskim were thrilled about this fact of life. But, still, a fact it was.

A quick scan of Responsa Project or Otzar will show not all Poskim were thrilled about this fact of life. But, still, a fact it was.

10. As scholars have noted, with the steady spread of Kabbalah from Safed in the prior centuries, Jews in the early 18th century tried to bring Kabbalistic rites and Kabbalist ethical literature into their daily lives.

11. The Shelah became popular.

And so did the Kitzur Shelah.

In fact, I think that while the Kitzur Shelah may have boosted the Shelah's (the book) popularity as much as the other way around in the 18th and 19th centuries.

And so did the Kitzur Shelah.

In fact, I think that while the Kitzur Shelah may have boosted the Shelah's (the book) popularity as much as the other way around in the 18th and 19th centuries.

12. It is also cited as the source of numerous prayers, customs, and prayer-related practices in later works.

Most famously, the Kitzur Shelah is the primary source for reciting verses corresponding to one's name after the Amidah and the codifier of which verses we are used

Most famously, the Kitzur Shelah is the primary source for reciting verses corresponding to one's name after the Amidah and the codifier of which verses we are used

13. It is also quoted in many other books of Halacha, ethics, and daily practice.

It is frequently mentioned in the Kaf haChaim (actually both of them), the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, and many many other works.

It is frequently mentioned in the Kaf haChaim (actually both of them), the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, and many many other works.

14. The Kitzur Shelah was also obviously the work of a Sabbatean author.

Indeed, while many noticed this in the 18th century and in our own times, they only scratch the surface of just how infused the work is with Sabbateanism.

Indeed, while many noticed this in the 18th century and in our own times, they only scratch the surface of just how infused the work is with Sabbateanism.

15. As we noted above, there are many editions of the Kitzur Shelah. Now, it is essential to recognize that they are not all the same or equal.

What version of the book one uses matters. People who have talked about it have had to work with the editions available to them.

What version of the book one uses matters. People who have talked about it have had to work with the editions available to them.

16. The first edition of such books is hard to come by. However, to fully address the work, we actually need each of the first three editions of the book.

17. They are:

A. First edition published Furth 5453

B. Second edition published Furth 5456

C. Third edition published Amsterdam 5461

A. First edition published Furth 5453

B. Second edition published Furth 5456

C. Third edition published Amsterdam 5461

18. These three editions were not only published during Epstein's lifetime, but he added a very substantial amount of new material in each of them.

The work as it was in Furth 5453 pales in comparison to the one it is in the Amsterdam 5461 version.

The work as it was in Furth 5453 pales in comparison to the one it is in the Amsterdam 5461 version.

19. Printings after Amsterdam 5461 are reproductions of the deluxe text unveiled in that one.

Any shift away from it should raise suspicions.

Post-mortem changes to a controversial but popular work raise questions.

Authors cannot edit the text from beyond the grave.

Any shift away from it should raise suspicions.

Post-mortem changes to a controversial but popular work raise questions.

Authors cannot edit the text from beyond the grave.

20. Except for Shnayer Leiman, who has traveled the world and seen everything on such topics, I doubt very much that most authors and, indeed, most readers have been able to read, interact, and view all three of these first editions.

Or compare them to each other & later ones

Or compare them to each other & later ones

21. Luckily, thanks to @NLIsrael, I have been able to work with all three.

And, indeed, several of the subsequent editions.

Now, I will try to share new evidence, new insights, and new analysis with you about Sabbateanism in the Kitzur Shelah:

And, indeed, several of the subsequent editions.

Now, I will try to share new evidence, new insights, and new analysis with you about Sabbateanism in the Kitzur Shelah:

22. Topic #1: Allusions to S.Z. in the Introduction and Parting Words of the Kitzur Shelah.

23. Most writers on the topic begin and end with evidence at the beginning and end of the Kitzur Shelah.

24. The Seforim blog features two very good discussions of the matter- written several years apart by different authors- that talk about it.

This one is about specific allusions to S.Z. in the intro to the book & much later attempts to cover it up:

seforimblog.com/2006/11/kitzur…

This one is about specific allusions to S.Z. in the intro to the book & much later attempts to cover it up:

seforimblog.com/2006/11/kitzur…

24a. This one, by Eli Genauer, discusses another clear reference to S.Z. as the messiah at the end of the book:

seforimblog.com/2011/11/change…

seforimblog.com/2011/11/change…

24b. It also features an email from Dr. Leiman on the topic that begins:

"Briefly, Kitzur Shelah is a Sabbatian work. It is suffused with Sabbatian material, so one needn’t look for evidence just at the beginning and end."

"Briefly, Kitzur Shelah is a Sabbatian work. It is suffused with Sabbatian material, so one needn’t look for evidence just at the beginning and end."

25. Leiman's words are vital here.

Going forward we will:

(A) Talk about examples at the start and end and (B) Discuss the controversy over the book in the 1700s

Then:

C. Dig deeper into the book to see remarkable (!!!) new examples of Sabbateanism in this text.

Going forward we will:

(A) Talk about examples at the start and end and (B) Discuss the controversy over the book in the 1700s

Then:

C. Dig deeper into the book to see remarkable (!!!) new examples of Sabbateanism in this text.

26. We know that the Kitzur Shelah was seen as a Sabbatean work already in the 1720s.

27. In a letter to R. Moshe Hagiz dated Tzom Gedalya 5486 (Sept. 1725),

R' E. Katzenellenbogen (i.e. the Knesset Yechezkel) told the anti-Sabbatean crusader that he ordered the confiscation of works of suspected Sabbateans in the triple community of AH"U (where he was Rav).

R' E. Katzenellenbogen (i.e. the Knesset Yechezkel) told the anti-Sabbatean crusader that he ordered the confiscation of works of suspected Sabbateans in the triple community of AH"U (where he was Rav).

28. The letter, preserved in Gahalei Esh (Oxford, Bodleian Library. Ms. 2186) makes clear that Katzenellenbogen ordered three works, in particular, to be turned over for containing Sabbatean materials.

One of them was the Kitzur Shelah.

(cf. Carlebach, Pursuit of Heresy 191)

One of them was the Kitzur Shelah.

(cf. Carlebach, Pursuit of Heresy 191)

29. More than 25 years later, R. Jacob Emden in תורת הקנאות (5512), in a portion where he lists Sabbatean books, makes reference to the Kitzur Shelah.

He writes:

גם רמז על הצוא"ה בהקדמת קצור של״ה

There is also a hint to הצוא"ה in the introduction to the Kitzur Shelah.

He writes:

גם רמז על הצוא"ה בהקדמת קצור של״ה

There is also a hint to הצוא"ה in the introduction to the Kitzur Shelah.

29b. Footnote:

I've noted this essay before.

But I want to point out again that Leiman unpacks this reference and the otherwise impenetrable section of Emden's תורת הקנאות in a fantastic article that can be found here:

leimanlibrary.com/texts_of_publi…

I've noted this essay before.

But I want to point out again that Leiman unpacks this reference and the otherwise impenetrable section of Emden's תורת הקנאות in a fantastic article that can be found here:

leimanlibrary.com/texts_of_publi…

30. Ok so what does Emden mean when he says there is a reference to הצוא"ה in the introduction.

First, צואה literally means feces in Hebrew.

Second, צואה has the Gematria of 102. And so does the word צבי.

Emden uses these devices to alert readers while insulting S.Z.

First, צואה literally means feces in Hebrew.

Second, צואה has the Gematria of 102. And so does the word צבי.

Emden uses these devices to alert readers while insulting S.Z.

30a. Side note: Beware, there are a lot of Gematria and other devices that are involved in this stuff.

Sabbateans loved Gematrias & hidden meanings (and took them very seriously)

Emden loved Gematrias & hidden meanings

So it's Gematria & hidden meanings all the way down.

Sabbateans loved Gematrias & hidden meanings (and took them very seriously)

Emden loved Gematrias & hidden meanings

So it's Gematria & hidden meanings all the way down.

31. So, basically, in תורת הקנאות he says that in the introduction to the Kitzur Shelah, Epstein makes an allusion to S.Z.

32. This is also not the only place Emden talks about this.

In a Responsa, he takes issue with a ruling made in the Kitzur Shelah about the laws of Challah and the tendency for people to follow pop compendiums like it.

Suffice it to say, Emden is punching down in this matchup.

In a Responsa, he takes issue with a ruling made in the Kitzur Shelah about the laws of Challah and the tendency for people to follow pop compendiums like it.

Suffice it to say, Emden is punching down in this matchup.

32a. (That is not a knock on the Kitzur Shelah. But, in reality, Emden is a halachic heavyweight in a generation of halachic heavyweights. Few would match up well against him).

33. He says that the ruling is a "big mistake" and gives his legal logic.

Then he continues by saying this is proof that you shouldn't listen to compendium books written by people who have not fit to make rulings.

Then he continues by saying this is proof that you shouldn't listen to compendium books written by people who have not fit to make rulings.

34. More, he says, if you knew what was indeed in Epstein's heart, you would never follow what he says even on a simple matter.

The rest is interesting in terms of Emden's personality.

But what is important for us is he tells them to go check out Epstein's introduction.

The rest is interesting in terms of Emden's personality.

But what is important for us is he tells them to go check out Epstein's introduction.

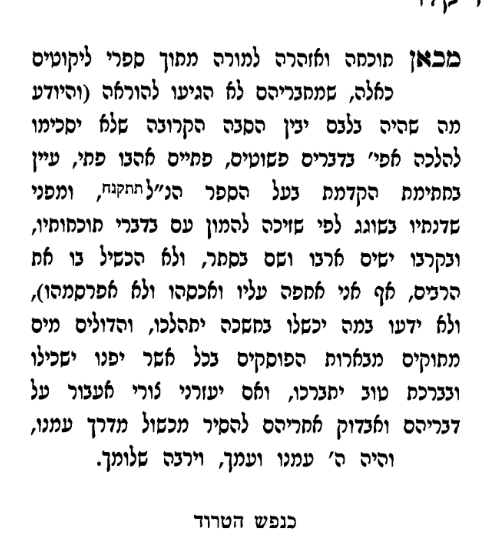

35. So let's see what Emden meant.

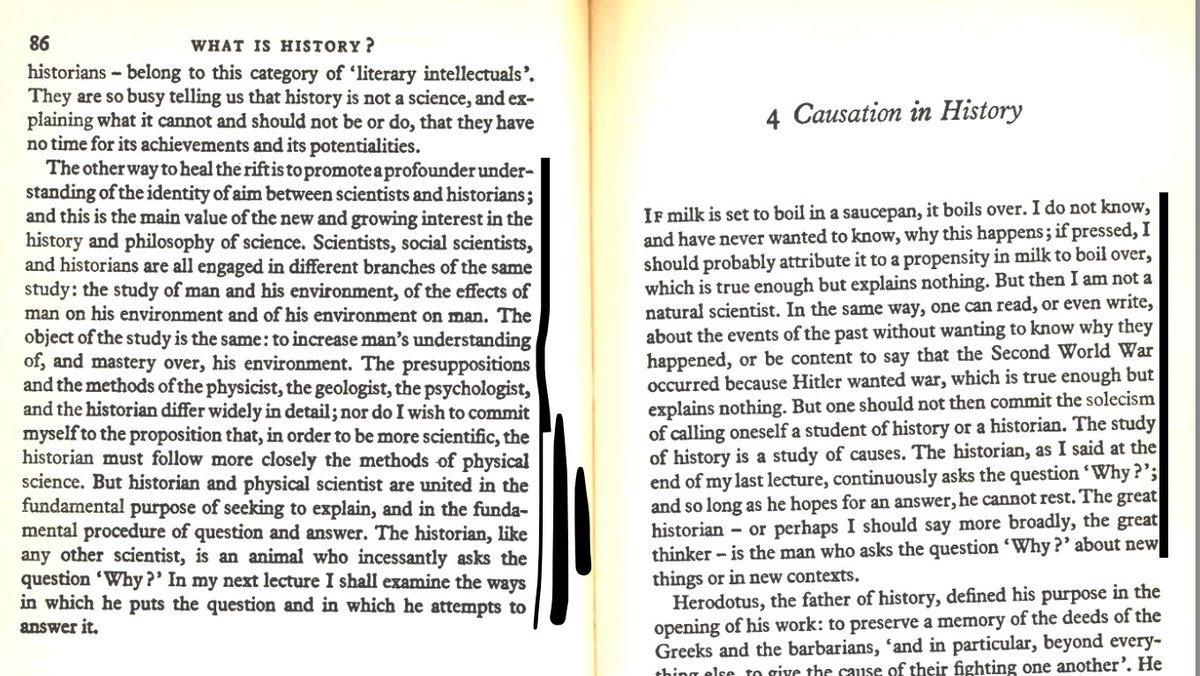

36. This is the title page of the very first edition of the Kitzur Shelah (Furth 5453/1692-93) at the National Library in Jerusalem

38. Starting at the end of the third to last line of the introduction, the author says:

my purpose in writing the book is that people should learn from it what to do and what not to do so that they should merit seeing the משי״ח האמ״תי and be worthy of ימו״ת המשי״ח

my purpose in writing the book is that people should learn from it what to do and what not to do so that they should merit seeing the משי״ח האמ״תי and be worthy of ימו״ת המשי״ח

39. The literal translation of these words should not make us very suspicious. Jews have been praying for a messiah for many thousands of years.

However, those exact words plus the use of those quotation marks in those words is very important

However, those exact words plus the use of those quotation marks in those words is very important

40. Those marks most of the time means:

a) that it is an abbreviation (which in this case it isn't)

b) the author is calling attention to some type of extra meaning or subtext

c) all of the above

a) that it is an abbreviation (which in this case it isn't)

b) the author is calling attention to some type of extra meaning or subtext

c) all of the above

40a. Note:

That does not mean that all words with subtexts/hidden meanings etc. will have those,

but it does mean that very often when they do have those, they probably will have a subtext/hidden meaning.

That does not mean that all words with subtexts/hidden meanings etc. will have those,

but it does mean that very often when they do have those, they probably will have a subtext/hidden meaning.

40b. Note:

Most subtexts/hidden meanings are innocuous or, at least, they have nothing to do S.Z.

So it's not enough to find those marks- you will find them someone in everyone's books- including those of Sasportas, Hagiz, and Emden

You have to figure out the hidden meaning

Most subtexts/hidden meanings are innocuous or, at least, they have nothing to do S.Z.

So it's not enough to find those marks- you will find them someone in everyone's books- including those of Sasportas, Hagiz, and Emden

You have to figure out the hidden meaning

41. In this case the hidden meaning is both:

- Related to Sabbateanism

- Easy to figure out as far as hidden Sabbatean references go (they are gonna get harder)

- Related to Sabbateanism

- Easy to figure out as far as hidden Sabbatean references go (they are gonna get harder)

42. Always start with the simple Gematria

משיח האמתי= 814

ימות משיח= 814

משיח האמתי= 814

ימות משיח= 814

43. (btw you will see I messed up in an earlier tweet when I said that it says ימות המשיח, not ימות משיח- which is what it actually says)

44. Well 814 is a pretty important number for Sabbateans because it is also the Gematria of שבתי צבי

45. As I said, Sabbateans took this very seriously the idea that משיח האמתי (true messiah) and ימות משיח (days of [the] messiah) equaled his name was not seen as a coincidence, but as proof to the messianic mission.

46. The use of משיח האמתי with or without the quotation marks is one of the most common Sabbatean Gematrias.

It was used during the mass movement and by faithful believers after the apostasy.

It was used during the mass movement and by faithful believers after the apostasy.

47. For example, Nathan of Gaza makes the subtext into the text here in "פירוש המראה שפי׳ מהר״ן הנביא נר״ו:"

והוא משי״ח האמית״י וכן עולה המנין ש״ץ

(as published in the really beautiful new edition of בעקבות משיח put out by @BlimaBooks)

blimabooks.com/collections/%D…

והוא משי״ח האמית״י וכן עולה המנין ש״ץ

(as published in the really beautiful new edition of בעקבות משיח put out by @BlimaBooks)

blimabooks.com/collections/%D…

48. Returning to Epstein

Take the allusion in context

He says: follow the instructions in the book- the ethical, kabbalistic, & halachic guides- to earn merit towards the return of the "true messiah;" namely, for him, SZ.

A mission statement for his pious Sabbatean opus

Take the allusion in context

He says: follow the instructions in the book- the ethical, kabbalistic, & halachic guides- to earn merit towards the return of the "true messiah;" namely, for him, SZ.

A mission statement for his pious Sabbatean opus

49. We might talk about later censorship of this passage, but I would just point out that it is present in the other two editions published in his life too.

50. Now, let's look at the other example in the public discourse.

This is brought by Eli Genauer in his post on the Seforim Blog.

seforimblog.com/2011/11/change…

Using the Amsterdam 1707 edition (namely, the fourth edition of the work):

This is brought by Eli Genauer in his post on the Seforim Blog.

seforimblog.com/2011/11/change…

Using the Amsterdam 1707 edition (namely, the fourth edition of the work):

51. This example can also be found in the three first editions of the book.

Here it is in the first edition (Furth 5453/1692-1693) from the National Library

Here it is in the first edition (Furth 5453/1692-1693) from the National Library

54. I will let Prof. Leiman, whose email is cited in the Seforim Blog article explain the allusion:

seforimblog.com/2011/11/change…

seforimblog.com/2011/11/change…

55. Now, we have covered some of the controversies in the 1700s on the work & brought the two best-known examples of the Sabbatean allusions in the text.

Now, it is time to dig deeper & provide new, exciting, & some really thought-provoking stuff

Now, it is time to dig deeper & provide new, exciting, & some really thought-provoking stuff

https://twitter.com/yonibrander/status/1570125191875022849

56. However, none of these have been mentioned in print by others

(that doesn't mean that hasn't ever been noticed- just no one has devoted themselves to making a massive list of all the possible Sabbatean references in the book)

(that doesn't mean that hasn't ever been noticed- just no one has devoted themselves to making a massive list of all the possible Sabbatean references in the book)

57. This means that no one is checking my work- but all of you- so I hope you start/continue with questions, adding other sources and references, & offering new suggestions.

https://twitter.com/yonibrander/status/1570382783943675904/retweets/with_comments

57a. It also means I'm counting on all of you.

I know old, new, & not-yet followers have exciting things to say on these topics

Pitch in references, comments, parallels, ideas, and questions.

Let's learn together!!!

I know old, new, & not-yet followers have exciting things to say on these topics

Pitch in references, comments, parallels, ideas, and questions.

Let's learn together!!!

57b. Last beat on this:

Also, be sure to like, RT, follow, and share this with people you think would like this.

I'm always looking to expand the community of learners.

Also, be sure to like, RT, follow, and share this with people you think would like this.

I'm always looking to expand the community of learners.

58. I'm going to officially end this thread here.

But the continuation of this one just started.

This is the first genuinely new conversation about more evidence on the topic of the Kitzur Shelah's Sabbateanism in some time:

But the continuation of this one just started.

This is the first genuinely new conversation about more evidence on the topic of the Kitzur Shelah's Sabbateanism in some time:

https://twitter.com/yonibrander/status/1570420304060600320

@UnrollHelper unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh