OK Part 2 of my @1972SHP “things-I-wish-every-new #historyteacher was-taught” thread.

Last time we looked at how new teachers learn. Today I want to think about why we are teaching history at all. /1

Last time we looked at how new teachers learn. Today I want to think about why we are teaching history at all. /1

Marc Bloch’s “The Historian’s Craft” opens with a child’s question: “Tell me, Daddy. What is the use of history?” It is a question deceptively simple because it requires an exploration of deep truths about what history is and is for. /2

At the age of 4, my own daughter asked me a similar question when I told her I trained history teachers: “Why do they want to teach history, Daddy?” Interestingly, this is the exact way I tend to open my course…by asking that question. Because purposes matter! /3

If you ask most people why they want to teach history, they will probably say something along the lines of the quotes below. History is, for many, an early warning system; or just something they find really interesting and want others to as well. /4

My follow up to this is normally to ask for examples. What 6 topics should all pupils know to prevent disasters in the future? Or which 6 areas of history are so fascinating that every child should know them? Many find this harder to articulate. /5

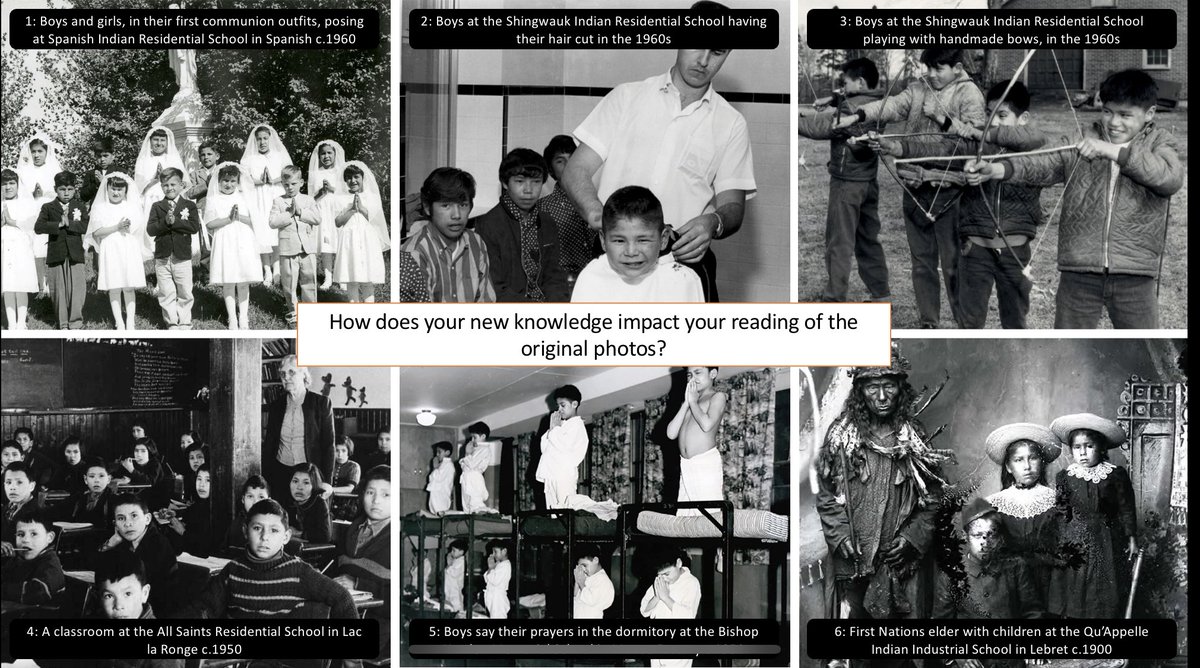

Broad purposes are all very good but they also need exploring through the concrete. It’s easier to convince someone history is worth studying if we can point to particular examples, or if we unpick what we actually mean when we talk about “mistakes” or “interest” /6

To make the point I go into a specific example and explore the purposes it might serve. I show trainee teachers the picture at the beginning of this thread and ask them why these Indignenous children, from a Canadian boarding school, should matter so much to them as teachers. /7

As we explore we use source materials and testimony to explore the horrors of the boarding school system. We begin to see how teachers’ purposes to assimilate through education were the root of horrific injustices which crushed bodies and spirits. /8

From this trainees often assume that the story of the children in the picture matters because it shows us the power teachers have over children for both good and ill. They are right, but there is much more. Why does this matter so much to history teachers in England? /9

We go on and look at the history of Indigenous peoples from the B colonial era in Canada. At the time of the photo, the children were under siege by a British settler state. I wonder how many of us looked at residential schools in Canada in our own history lessons in the UK? /10

These children matter because they are part of a story we often fail to tell. And this is despite the fact the National Curriculum demands a coherent knowledge of Britain’s past - and by extension the people directly impacted by British colonialism, like these children. /11

It is too easy to ignore this story if we are not driven by a purpose to engage with Britain’s colonial history.

From this, + associated tasks, we draw three key lessons (outlined below). What we teach matters. How we teach matters. Our purposes help us navigate this work /12

From this, + associated tasks, we draw three key lessons (outlined below). What we teach matters. How we teach matters. Our purposes help us navigate this work /12

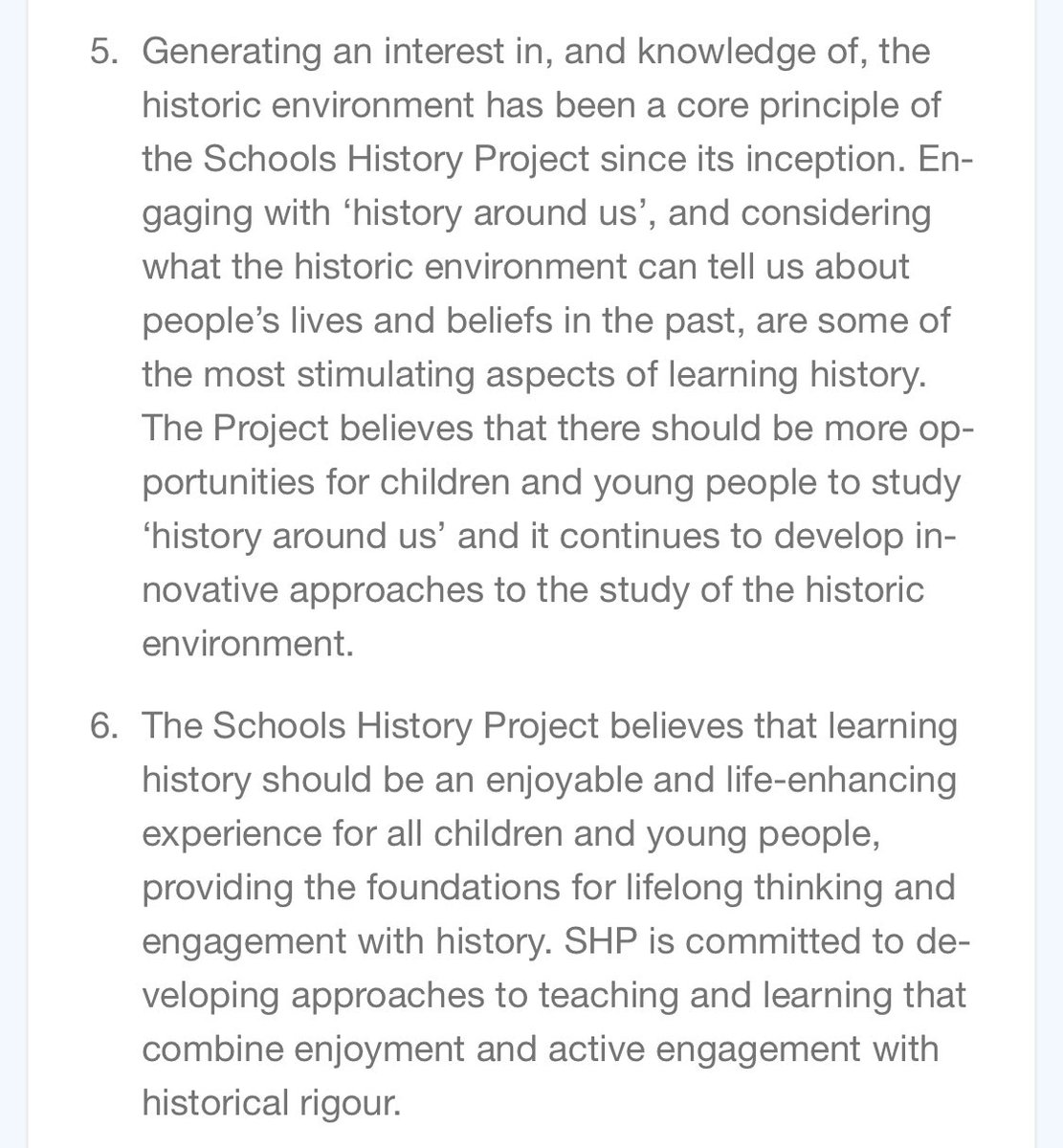

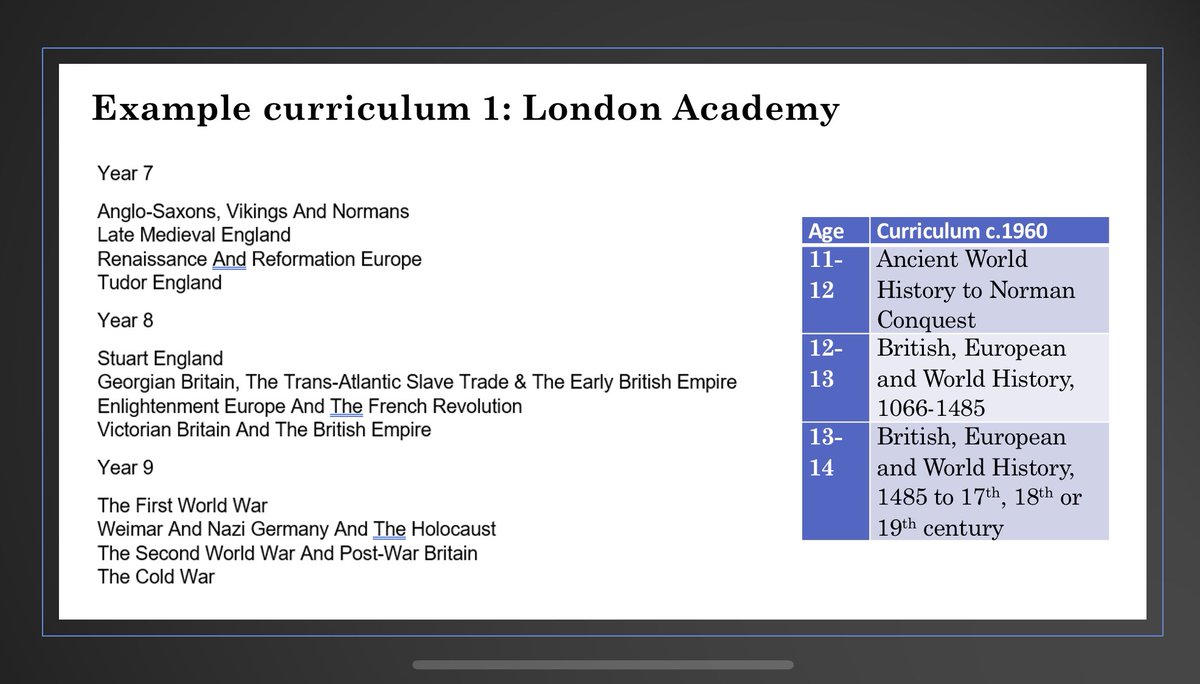

So here’s an interesting exercise connected with purposes. Have a look at the National Curriculum. It opens with a set of fairly diverse purposes. Compare these to other sets of purposes, such as those enshrined in the @1972SHP principles. How similar or different are they? /13

Next have a look at some curriculum models. Consider how each set of purposes might cause you to approach the teaching and content quite differently. The NC purposes might lead to a study of the Crusades as a traditional causal narrative of crusader motives /14

By contrast SHP principles might lead to a focus on the ways in which the crusades altered Muslim-Christian relations in the Middle Ages and beyond. Purposes fundamentally alter how we approach content. /15

What about causes of the Industrial Revolution? For most people their own experience at school would have been focused on “great men”, inventions, transportation, and internal migration. It is easy to give little thought to purposes and replicate this as teachers too. /16

But if we set out with a purpose to reveal the forces which continue to shape our present, then the causes necessarily include colonialism, enslavement, racial discrimination, dispossession etc. We need to see “the sugar at the bottom of the cup”, as Stuart Hall put it. /17

If we don’t think carefully about our purposes it’s all too easy to create a narrow, white, male, upper class curriculum - not because we want to, but because we’ve not thought carefully enough to avoid it. We’ve seen this happen too often in the recent past /18

If you’re interested in my thoughts on why the misinterpretation of the concept of “powerful knowledge” has contributed to bringing us to that point, you can find a longer article here uclpress.scienceopen.com/hosted-documen…

And this matters for several reasons:

First, it reproduces injustices and silences histories of the oppressed and dispossessed.

Second, it robs history of its salience and turns it into, as Alan Bennett immortalised it, “just one f*ing thing after another” /19

First, it reproduces injustices and silences histories of the oppressed and dispossessed.

Second, it robs history of its salience and turns it into, as Alan Bennett immortalised it, “just one f*ing thing after another” /19

The same is true if we narrow ourselves to narrow performative purposes - often achieving specific exam results - which shape and guide choices more than broader purposes. Exams matter, but good education is far more than exams. /20

However, purposes and principles can also lead us astray if they are not also rooted in a concern for truth, human rights and equal dignity. They can also trio us up if we are not open to being critical about them. Purposes need deep thought and repeated revisiting /21

I doubt many today would agree with some of the purposes outlined below for example. Yet many of these purposes were commonplace in schools of the last century. We have come a long way, but the road back is much shorter if we don’t take care /22

In conclusion then, I hope that every history teacher wrestles with the purposes which drive their work, not only at the start, but throughout their careers. This soul searching, as Bloch would put it, is the only way to ensure history contributes to greater justice /22

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh