Having monitored Russia's war narratives since the invasion began, one thing is puzzling: some narratives quickly faded from broadcast media, yet remain in active circulation. How?

A short 🧵on the double lives of Russia's war narratives (aka my #APSA2022 paper) 1/9

A short 🧵on the double lives of Russia's war narratives (aka my #APSA2022 paper) 1/9

(For background on previous findings from both federal and regional broadcast media, you can check out this earlier thread):

2/9

https://twitter.com/jpaulgoode/status/1543269668105981958

2/9

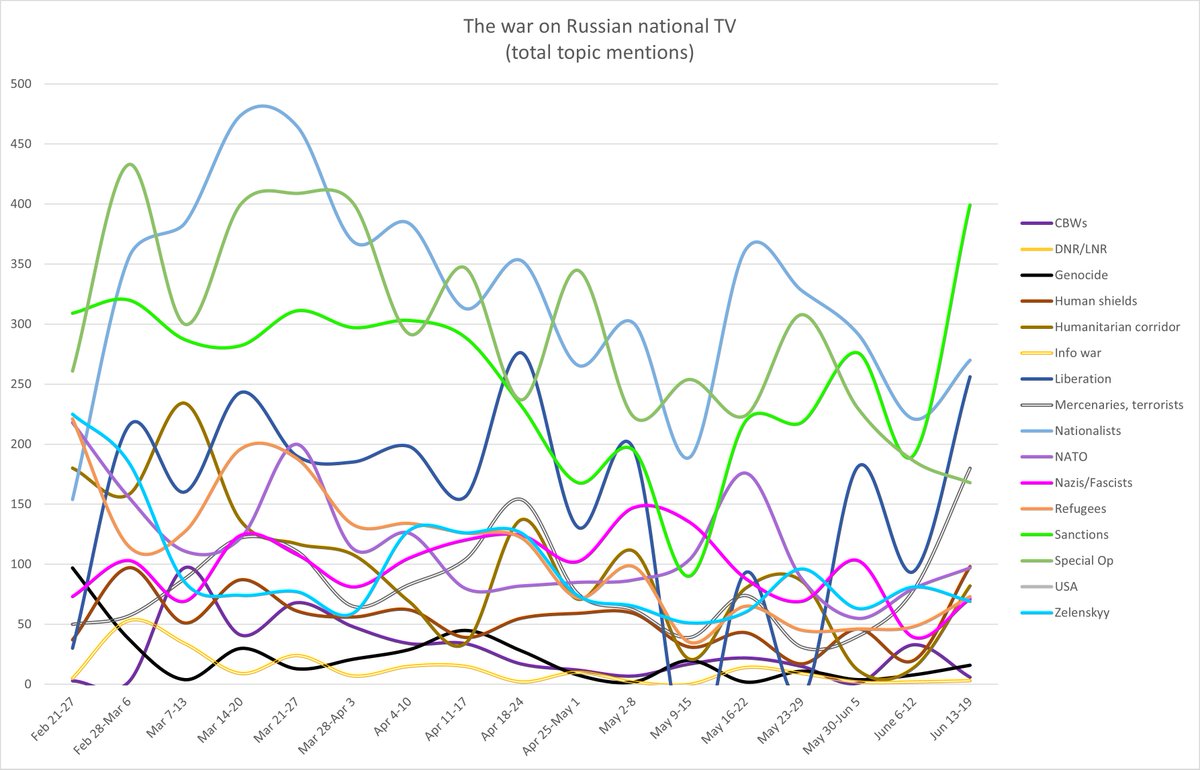

Looking at federal TV, we see a familiar tangle of war narratives. There's just one narrative that rises about all others: Ukrainian nationalists as Russia's enemy. Justifications for the war faded esp. after Mariupol. Schemes against Russia are reduced to sanctions.

3/9

3/9

The situation is even more stark on regional tv & radio, where only sanctions get significant notice. Every other narrative is reported less frequently than the weather, meaning in practice that they aren't all that salient in everyday life.

4/9

4/9

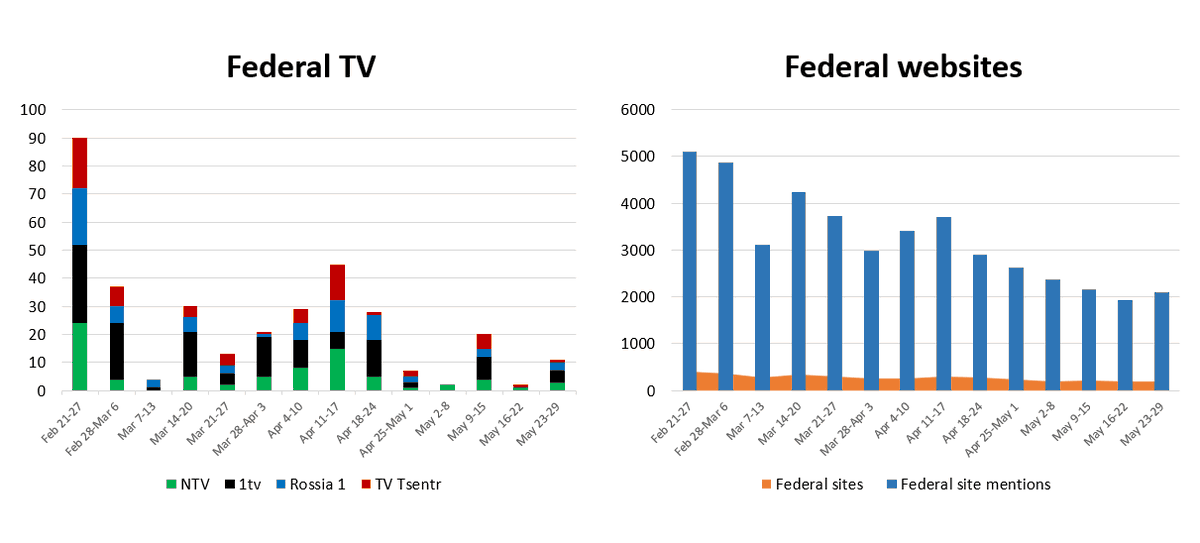

But even when narratives no longer register on tv, they continue to be circulated and amplifed online. For ex., the narrative that Russia invaded to stop genocide was loudly claimed at the start of the war and quickly abandoned on tv, but it took on another life online.

5/9

5/9

The majority of these references to genocide were driven by a handful of websites, with the top 3 websites accounting for as much as 50% of mentions. The top sites usually include RIA Novosti and another news site, but also pro-Kremlin blogs and special interest sites.

6/9

6/9

Most of these not only repeat the genocide claim but even replicate phrasing. Kommersant mentioned genocide 133 times in the last week of May. The same sentence could be found in paragraphs appended to 243 stories published online by "rusunlimited.ru" that same week.

7/9

7/9

One finds similar dynamics in mentions of the Ukrainian nationalists narrative. While it almost completely disappeared from regional tv & radio, it continues to thrive on regional websites in similar fashion to the genocide claim.

8/9

8/9

There's more to tell, but the upshot is that Russia war narratives take on double lives. They are seeded into national audiences on tv & radio and then move online for amplification and circulation...including well beyond Russia (but that's another story). 9/9

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh