How did the rise of capitalism affect human welfare? Did it make poverty better or worse? Where did progress come from?

We have a new study that explores these questions, looking at 500 years of data. It's a troubling but also inspiring story... 🧵 sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

We have a new study that explores these questions, looking at 500 years of data. It's a troubling but also inspiring story... 🧵 sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

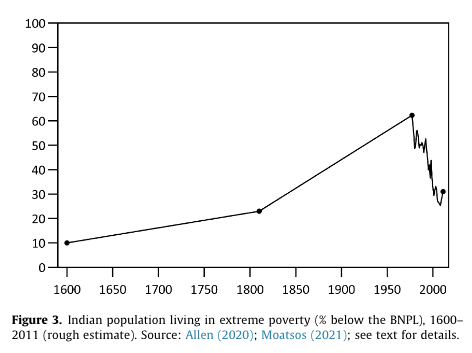

Existing narratives tend to rely on historical GDP and PPP data. This is useful to show how total production and consumption has increased over time, but it often does not adequately account for changes in access to essential goods, particularly during periods of dispossession.

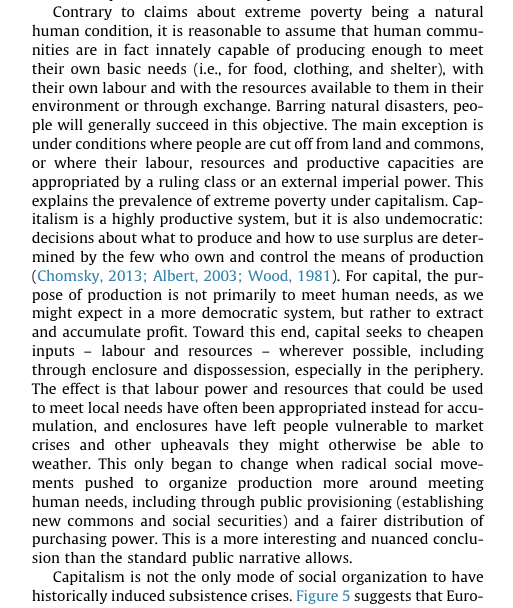

Scholars have been aware of this problem for a long time. Robert Allen has argued that we should measure poverty directly, in terms of people's ability to meet basic needs. When we do, a rather striking story emerges. Here's the extreme poverty rate in India:

Data from pre-colonial India shows that extreme poverty tended to be relatively low. Poverty increased as India was forcibly integrated into the capitalist world-system. Allen notes that mass poverty in the mid-20th c is a modern phenomenon, "a development of the colonial era".

Unfortunately, this sort of data is not available for most of the world. So we track three indicators of welfare (real wages, human height, and mortality) to see how people's lives changed with the rise of capitalism in five world regions.

What does this data show?

What does this data show?

First, the rise of capitalism from the 1500s onward was associated with a dramatic deterioration in human welfare (declining wages, declining heights, and an increase in premature mortality), in all five regions. In some cases, wages and/or heights have still not recovered.

I should emphasize that by capitalism here we do not mean a generic system of markets and trade. It is a world-system where production is organized around elite accumulation and corporate power, which involves "core" states subordinating and extracting from "peripheral" regions.

These results are striking, but not surprising. The global expansion of capitalism often involved dispossession, enslavement, coerced labour, genocide, colonisation, policy-induced famines, and destruction of subsistence economies. The effects are visible in the empirical record.

During the period of capitalist integration, we see increased famines in Europe (1500s-1800s); demographic collapse in the Americas; a 15% population decline in Central/East Africa (1890-1920); ∼100 million excess deaths in India (1880-1920), and so on. Massive dislocation.

Fortunately, for most people life has improved considerably since then. And this brings us to our second conclusion:

Where progress has occurred, it began several hundred years after capitalist integration... around 1880s in the core, and early/mid 20th c in the periphery.

Where progress has occurred, it began several hundred years after capitalist integration... around 1880s in the core, and early/mid 20th c in the periphery.

Where did progress come from? Well, it coincided with the rise of labour movements, democracy movements, socialist movements and anti-colonial movements that fought to organize production around human needs and public provisioning, quite often against the interests of capital.

As many scholars have argued, progress comes from progressive social movements - it is not spontaneously bequeathed by capital, or the processes of capital accumulation. In the words of Thomas Sankara: we are the heirs of the world's revolutions.

The paper is open access and has fourteen graphs, which we interpret in the text. For those who want to dig into the details, there are 19 pages of appendices (!). Big credit goes to the brilliant Dylan Sullivan, and the many colleagues who contributed insights along the way.

I want to emphasize that this work is focused on *extreme poverty* (access to basic food, fuel, etc). A key implication of the paper is because extreme poverty is not a natural condition, it should not be used as a benchmark for progress. Extreme poverty should not exist, period.

It is obvious that higher levels of welfare require higher consumption, things like vaccines, modern healthcare, refrigeration, clean-fuel stoves, transit, etc etc – goods that did not exist in the past. This is where industrialization becomes so important.

The key question is: how is industrial capacity used? Is it used to secure decent lives for all, or to maximize capital accumulation? How are workers treated? This depends on the political system, the provisioning system, and the balance of class power. More on this soon.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh