The Chancellor is expected to announce a large package of permanent tax cuts on Friday without a new set of forecasts from the OBR. This is disappointing.

So, in the absence of official scrutiny from the OBR, we @TheIFS have stepped into the breach. 🧵

So, in the absence of official scrutiny from the OBR, we @TheIFS have stepped into the breach. 🧵

In short, the government is planning a substantial package of permanent tax cuts that will mean a sharp and sustained increase in borrowing, just as borrowing becomes more expensive, in a gamble on growth that may not pay off. You can't assume your way to fiscal sustainability.

You can read the full report by my colleagues here. This is part of the IFS Green Budget & funded by @NuffieldFound. The analysis is based on a new set of macroeconomic forecasts from Citi.

Here, I just want to draw out a few things.

ifs.org.uk/publications/r…

Here, I just want to draw out a few things.

ifs.org.uk/publications/r…

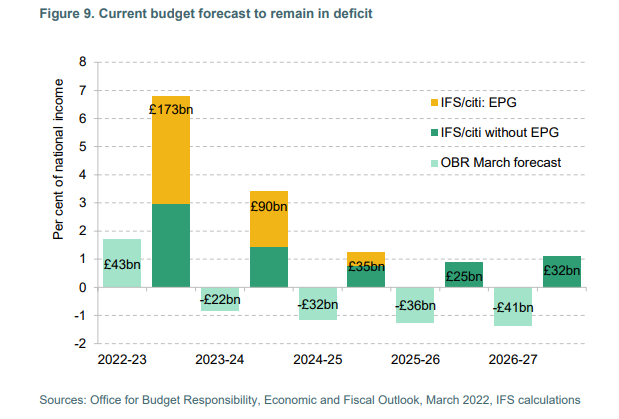

Under these forecasts, a worsening economic outlook and a big package of tax cuts mean that even once the (enormous) Energy Price Guarantee has expired, borrowing would be running at ~£100bn/year (~3.5% GDP) into the mid 2020s. That's ~£70bn/year more than was forecast in March.

That would mean:

1) A persistent current budget deficit (i.e. borrowing to finance day-to-day spend)

2) Debt on a steady upwards path as a share of national income

i.e. the existing fiscal targets (legislated in January) missed by a wide margin

1) A persistent current budget deficit (i.e. borrowing to finance day-to-day spend)

2) Debt on a steady upwards path as a share of national income

i.e. the existing fiscal targets (legislated in January) missed by a wide margin

(side note: this is all based on policy as currently announced. If the Chancellor announces further tax cuts on Friday, that would change things and almost certainly mean even higher borrowing. In that case we'd of course update after the fact)

Borrowing more and allowing debt to rise temporarily to finance one-off support packages in a crisis (e.g. furlough, energy price guarantee) is justifiable and can be sustainable.

The same cannot be said for allowing debt to rise indefinitely to enjoy lower taxes now.

The same cannot be said for allowing debt to rise indefinitely to enjoy lower taxes now.

In other words, temporary, time-limited measures need to be thought of separately to any permanent changes to tax and spending. The latter ought not to be announced outside of a 'proper' fiscal event and without scrutiny from the OBR.

This sharp increase in borrowing will take place amidst rising gilt yields (not just in the UK, but globally), which makes that borrowing more expensive. The Bank won't be stepping in to buy bonds either - they're looking to unwind QE. It's not risk-free.

https://twitter.com/faisalislam/status/1572239855173746689?s=20&t=rkvs9M_W5Rqt_B5gPed_XA

Finding a way to somehow boost the UK's (meagre) rate of economic growth would undoubtedly help and be good news for the public finances. But there's no simple miracle cure. We get a new 'plan for growth' most years. No guarantee it will materialise. Relying on it is a gamble.

There's lots more detail in the full piece, which you can find at the link above. We've also got an event tomorrow where we'll be talking through this analysis (among other things), and answering questions. Come along!

ifs.org.uk/events/look-ah…

ifs.org.uk/events/look-ah…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh