This painting is 600 years old.

And that mirror in the background is barely ten centimetres across, yet it contains a reflection of the entire room.

Including the artist at work, one of the greatest painters who ever lived, a man called Jan van Eyck...

And that mirror in the background is barely ten centimetres across, yet it contains a reflection of the entire room.

Including the artist at work, one of the greatest painters who ever lived, a man called Jan van Eyck...

Jan van Eyck (1390-1441) was the greatest painter of the Early Renaissance in Northern Europe.

We'll get to his brilliance, but the first thing to understand is that the Renaissance in Northern Europe was different to the Italian Renaissance of Leonardo and Michelangelo...

We'll get to his brilliance, but the first thing to understand is that the Renaissance in Northern Europe was different to the Italian Renaissance of Leonardo and Michelangelo...

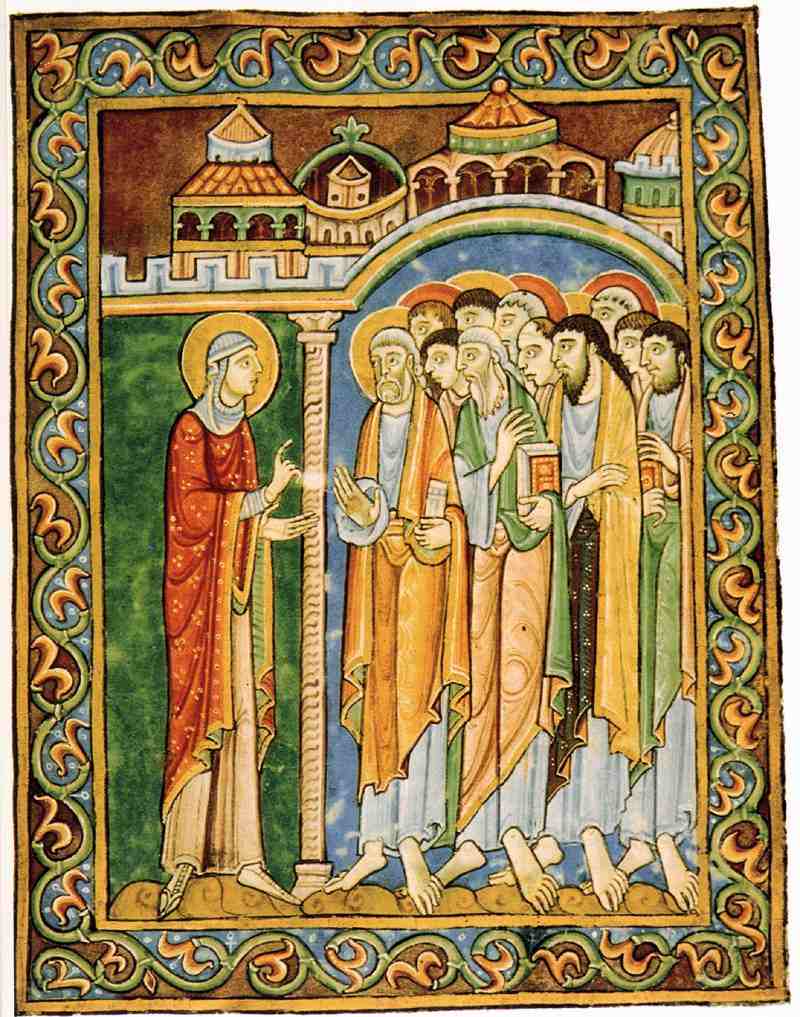

See, this is what Medieval art looked like before the Renaissance.

It was about telling the stories of the Bible and of Christian myth in visual form.

Realism didn't matter to these artists; they focussed on what was important to them.

It was about telling the stories of the Bible and of Christian myth in visual form.

Realism didn't matter to these artists; they focussed on what was important to them.

So things like perspective and depth weren't a feature of Medieval art. Saints weren't drawn "realistically" - it was more important that they could be recognised.

Often their paintings weren't set in a specific place; the background was decorative, even plain gold.

Often their paintings weren't set in a specific place; the background was decorative, even plain gold.

And this disinterest in realism led these artists to embrace quite wonderful compositional patterns.

Much Medieval art was beautifully ornate and semi-abstract:

Much Medieval art was beautifully ornate and semi-abstract:

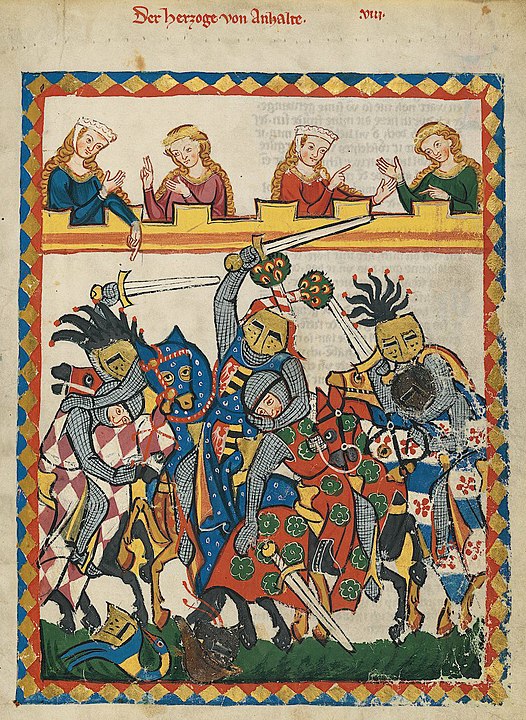

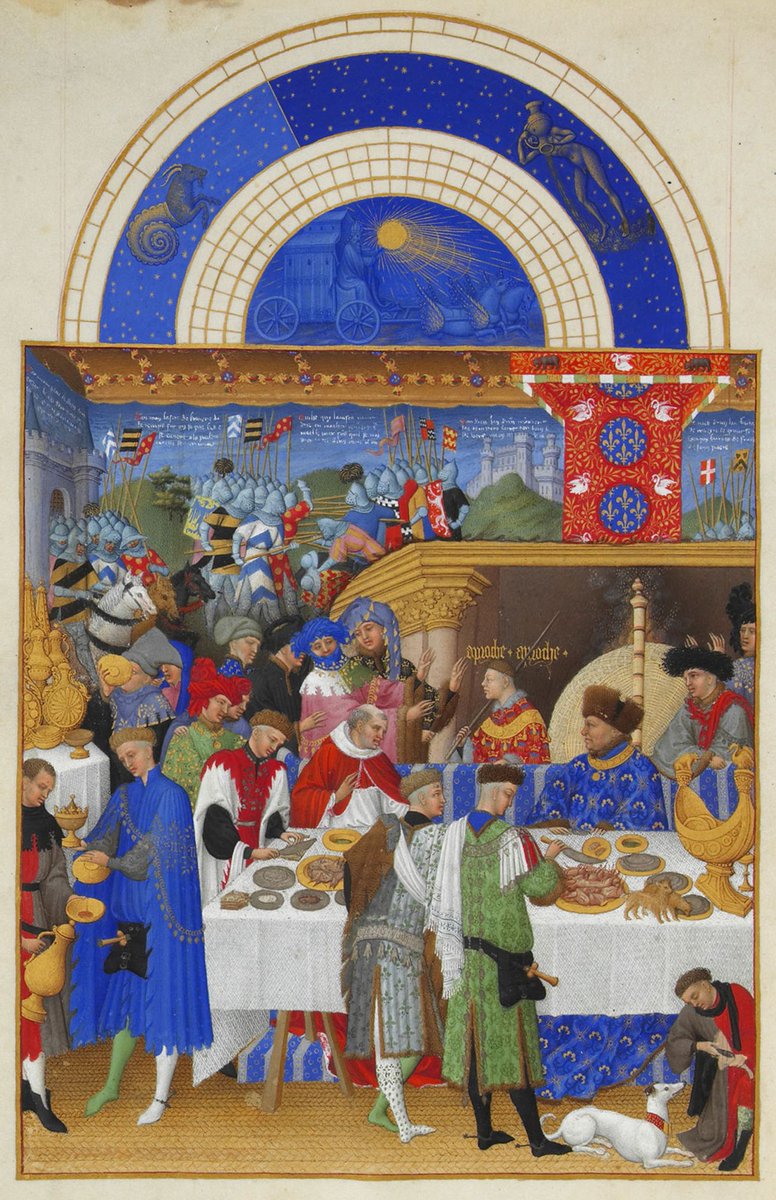

And, as time went by, they didn't just paint scenes from the Bible. They also depicted life in the Middle Ages: of feasts, hunts, and knightly tournaments.

The ordinary world was now a part of Medieval art.

The ordinary world was now a part of Medieval art.

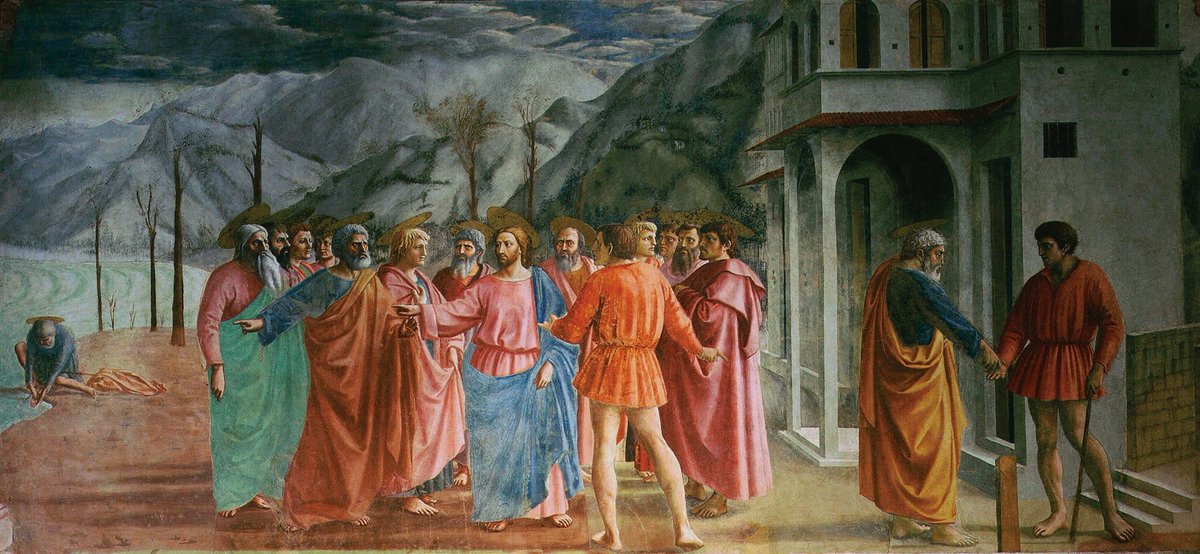

But in Italy - first through Giotto in the early 1300s, followed by Masaccio a century later - perspective was introducted into art.

Paintings were now three-dimensional. People had weight. They seemed to be standing in real places. Things became more realistic.

Paintings were now three-dimensional. People had weight. They seemed to be standing in real places. Things became more realistic.

In Italy this discovery led artists to attempt a conquest of reality. They mastered the skill of painting human forms as they truly appear.

More than that - inspired by Roman statues - they sought to idealise the human form. Compare these two versions of the Annunciation:

More than that - inspired by Roman statues - they sought to idealise the human form. Compare these two versions of the Annunciation:

This Classical interest in "ideal beauty" did not spread to Northern Europe, but the discovery of perspective did.

Enter the "International Gothic" style of the late 14th century. Those formerly flat and quasi-abstract Gothic paintings now had depth:

Enter the "International Gothic" style of the late 14th century. Those formerly flat and quasi-abstract Gothic paintings now had depth:

But they retained much of the same flamboyance and extravagance and cluttered compositions of traditional Medieval art.

That interest in patterns had transformed into a fascination with detail - the detail of armour, stone, cloth, and embroidery.

That interest in patterns had transformed into a fascination with detail - the detail of armour, stone, cloth, and embroidery.

And this produced a real difference in style between Northern Europe and Italy.

Whereas the great Italian artists of the age were painting scenes from Biblical and Classical mythology with a focus on ideal beauty, realistic forms, and clean, harmonious compositions...

Whereas the great Italian artists of the age were painting scenes from Biblical and Classical mythology with a focus on ideal beauty, realistic forms, and clean, harmonious compositions...

The Northern European painters were simply using these new artistic skills to enhance their existing interest in the messages of the Bible, of ordinary life, and of detailed patterns.

Like in the work of the great Limbourg Brothers in the early 15th century:

Like in the work of the great Limbourg Brothers in the early 15th century:

And so finally we come to Jan van Eyck, born in the Netherlands in 1390, who would take Gothic art to its extreme.

His greatest achievement was to bring an almost unbelievable realism of detail and texture to painting:

His greatest achievement was to bring an almost unbelievable realism of detail and texture to painting:

His artistic heritage - of Gothic ornateness and disinterest in idealism - led him to focus very deeply on the texture of *things* as they actually appeared.

He added layer upon layer of detail until they became - via a different method to the Italians - realistic.

He added layer upon layer of detail until they became - via a different method to the Italians - realistic.

A key part of Jan van Eyck's story is his use of oil painting.

Some say he actually invented it; others disagree. It doesn't matter. The point is that he mastered oil paint and learned that adding multiple, thin, translucent layers created vivid colours and textures:

Some say he actually invented it; others disagree. It doesn't matter. The point is that he mastered oil paint and learned that adding multiple, thin, translucent layers created vivid colours and textures:

Consider his depiction of the Virgin Mary from the masterful Ghent Altarpiece, completed in 1432.

It's like you used AI to create a photorealistic Gothic painting.

Just look at the book, jewels, and cloth - the verisimilitude is astonishing:

It's like you used AI to create a photorealistic Gothic painting.

Just look at the book, jewels, and cloth - the verisimilitude is astonishing:

Remember that van Eyck was doing all this before Leonardo da Vinci was even born.

Nonetheless, consider the very best art of the idealising Italian Renaissance.

It is beautiful, beyond doubt; but the minute details are less exquisite than those of van Eyck.

Nonetheless, consider the very best art of the idealising Italian Renaissance.

It is beautiful, beyond doubt; but the minute details are less exquisite than those of van Eyck.

However, you can see the effect of van Eyck's Gothic heritage.

His textures are luminous, but his figures can look somewhat stiff, wooden, and lifeless when compared with those of Italian art:

His textures are luminous, but his figures can look somewhat stiff, wooden, and lifeless when compared with those of Italian art:

But van Eyck wasn't interested in that.

The Arnolfini Portrait is a masterpiece of detail and a certain kind of realism; even if the Italians conquered the human form, not even Michelangelo could hold a candle to van Eyck's depiction of the material world:

The Arnolfini Portrait is a masterpiece of detail and a certain kind of realism; even if the Italians conquered the human form, not even Michelangelo could hold a candle to van Eyck's depiction of the material world:

And the mirror - that mirror! - surely deserves to go down as one of greatest achievements in the history of art.

Not only for its attention to detail but also because we can see Jan van Eyck in it, painting the couple as they pose for their portrait, and therefore also his own.

Not only for its attention to detail but also because we can see Jan van Eyck in it, painting the couple as they pose for their portrait, and therefore also his own.

So, in a way, van Eyck represents the culmination of Gothic art.

His paintings are a direct descendent of those old illuminated manuscripts; he took the Gothic fascination with detail and pattern as far as it could possibly go.

His paintings are a direct descendent of those old illuminated manuscripts; he took the Gothic fascination with detail and pattern as far as it could possibly go.

The Northern Renaissance diverged from its Italian equivalent in fascinating ways - and shows how different *interests* can produce such different art.

Painters like van Eyck are less famous than their Italian counterparts, but no less brilliant.

Painters like van Eyck are less famous than their Italian counterparts, but no less brilliant.

And here is a possible portrait of the man himself.

One of the greatest painters who ever lived, whose attention to detail, mastery of oils, and scrupulous recreation of the textures of our world boggles the mind even to this day.

One of the greatest painters who ever lived, whose attention to detail, mastery of oils, and scrupulous recreation of the textures of our world boggles the mind even to this day.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh