Do you ever feel that some cities are just more alive than others?

It's probably because they're "mixed-use".

This is a simple idea, but it changes everything...

It's probably because they're "mixed-use".

This is a simple idea, but it changes everything...

It's in the name.

An area of a city (or town) is mixed-use when you've got residential, commercial, and cultural buildings all together, perhaps even sharing the same site.

The opposite is "single use", where an area has only one purpose.

An area of a city (or town) is mixed-use when you've got residential, commercial, and cultural buildings all together, perhaps even sharing the same site.

The opposite is "single use", where an area has only one purpose.

Imagine a street with shops and services on the ground-level (everything from banks to hairdressers to bakeries to supermarkets) and apartments on the floors above, with cafes, restaurants, a library, a cinema, schools, and offices all thrown in.

That is mixed use.

That is mixed use.

Rather than endless suburbs in which there are *only* houses, and at best a cornershop here or there.

And beyond the suburbs a shopping mall or two, plus a business park full of offices in the distance.

Where all the parts of a human settlement are separated.

And beyond the suburbs a shopping mall or two, plus a business park full of offices in the distance.

Where all the parts of a human settlement are separated.

Americans who come to Europe seem to notice this.

They go to places like Paris and remark how "vibrant" or "alive" or even "authentic" the place feels.

But it isn't just Paris, and mixed-use isn't just for major cities.

They go to places like Paris and remark how "vibrant" or "alive" or even "authentic" the place feels.

But it isn't just Paris, and mixed-use isn't just for major cities.

It's generally the older parts of towns that are mixed use.

Which makes sense. Over time, as a town grew organically, people would build what was needed, and they would built it where it was needed - where they lived.

Which makes sense. Over time, as a town grew organically, people would build what was needed, and they would built it where it was needed - where they lived.

And the result is, indeed, a "vibrant" town or city.

Because people are living, working, shopping, eating, or whatever, all in the same place.

It produces communities where people live close to their pubs, churches, town halls, or wherever they choose to gather.

Because people are living, working, shopping, eating, or whatever, all in the same place.

It produces communities where people live close to their pubs, churches, town halls, or wherever they choose to gather.

So we shouldn't imagine that "mixed-use" cities are only the result of careful urban planning by qualified experts.

In reality, people *naturally* produce mixed-use spaces.

Urban planning is actually responsible for creating many single-use spaces in the first place...

In reality, people *naturally* produce mixed-use spaces.

Urban planning is actually responsible for creating many single-use spaces in the first place...

It was the Industrial Revolution that first led modern cities to be laid out according to specific plans in which there were different "zones" for different purposes.

For example, you'd have a factory surrounded by houses for the workers.

For example, you'd have a factory surrounded by houses for the workers.

As time went on such zoning became more frequent. The motivations were sometimes good, perhaps out of concern for public health.

Other times they were bad: to protect house prices in "nicer" areas.

And at times it was mere expedience; they did what was easiest.

Other times they were bad: to protect house prices in "nicer" areas.

And at times it was mere expedience; they did what was easiest.

The problem of zoning, whether mandated or incidental, has been exacerbated by the rise of the car.

Planners didn't need to mix up the purpose of an area; they could just build vast suburbs, safe in the knowledge that inhabitants could drive wherever they needed to go.

Planners didn't need to mix up the purpose of an area; they could just build vast suburbs, safe in the knowledge that inhabitants could drive wherever they needed to go.

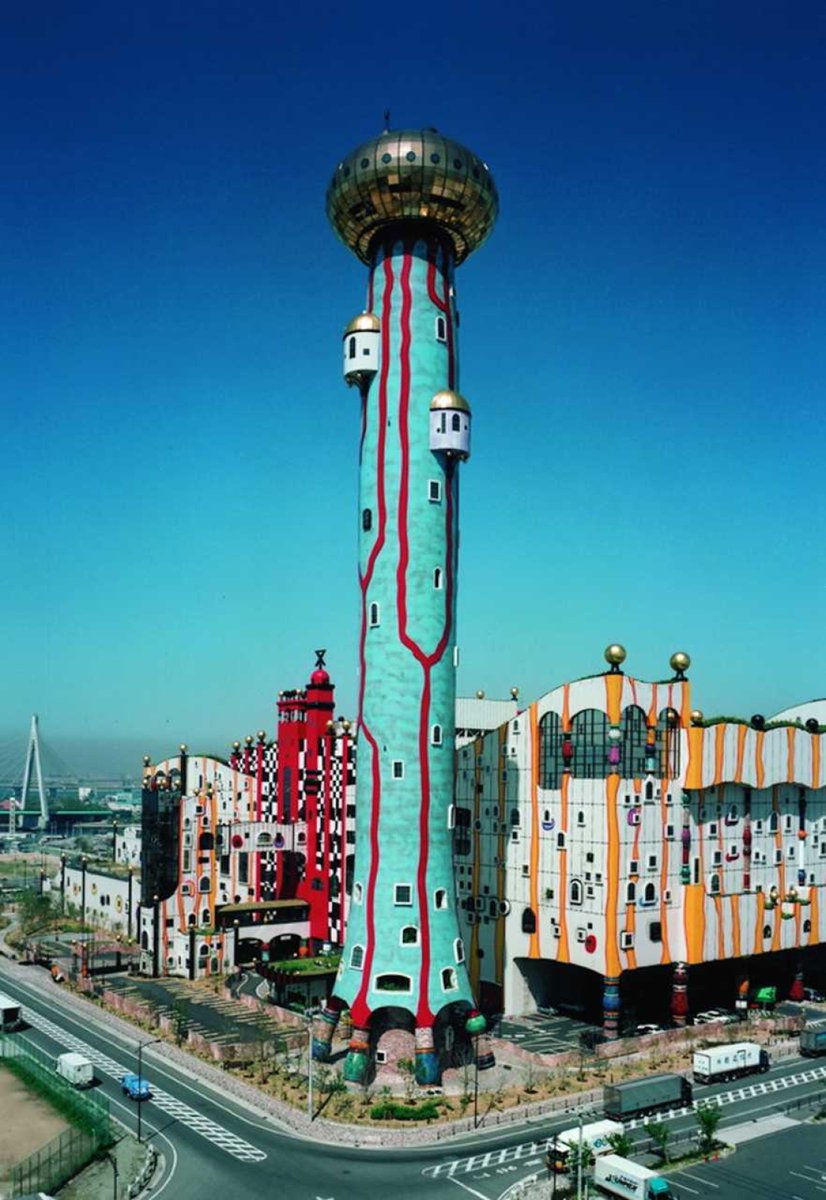

That being said, urban planning is to thank for some of the best mixed-use examples.

After all, when Haussmann demolished half of Medieval Paris in the 1850s, and when Cerdà did the same to Barcelona, they were conscious of residential, commercial, and transport needs.

After all, when Haussmann demolished half of Medieval Paris in the 1850s, and when Cerdà did the same to Barcelona, they were conscious of residential, commercial, and transport needs.

But that continental European idea of a high-density city did not spread to the Anglosphere. For example, it was low-density "New Towns" that became popular in Britain.

These had long suburban streets separated commercial from residential areas.

These had long suburban streets separated commercial from residential areas.

And, after the Second World War, housing shortages led governments to build "overspill" estates, comprised purely of residential buildings around the edge of existing urban centres, to deal with population increase.

A solution of quality, not quantity.

A solution of quality, not quantity.

Mixed-use development will not solve all a city's problems.

But it has an awful lot of fascinating and quite beneficial consequences.

One of the best is how it reduces our reliance on cars. When shops, work, or amenities are in the immediate vicinity, you don't need to drive.

But it has an awful lot of fascinating and quite beneficial consequences.

One of the best is how it reduces our reliance on cars. When shops, work, or amenities are in the immediate vicinity, you don't need to drive.

Which, among many other advantages, will reduce the presence of cars on streets.

More than that, it will preclude the need to *design* new urban areas around the need for cars.

More than that, it will preclude the need to *design* new urban areas around the need for cars.

Another vital benefit of mixed-use areas is that they encourage community.

It doesn't mean everybody will be best friends with their neighbours, but it does add a sense of identity and belonging, and produces a more idiosyncratic, localised atmosphere.

It doesn't mean everybody will be best friends with their neighbours, but it does add a sense of identity and belonging, and produces a more idiosyncratic, localised atmosphere.

Just compare these two coffee places to see how something as intangible as community or culture can arise from mixed-use rather than single-use urban planning:

And it certainly increases social contact, which is sorely lacking in the single-use urban areas of the 21st century, where people live online, isolated from one another.

In a very simple way, you're less likely to order things online if there's a shop thirty seconds away.

In a very simple way, you're less likely to order things online if there's a shop thirty seconds away.

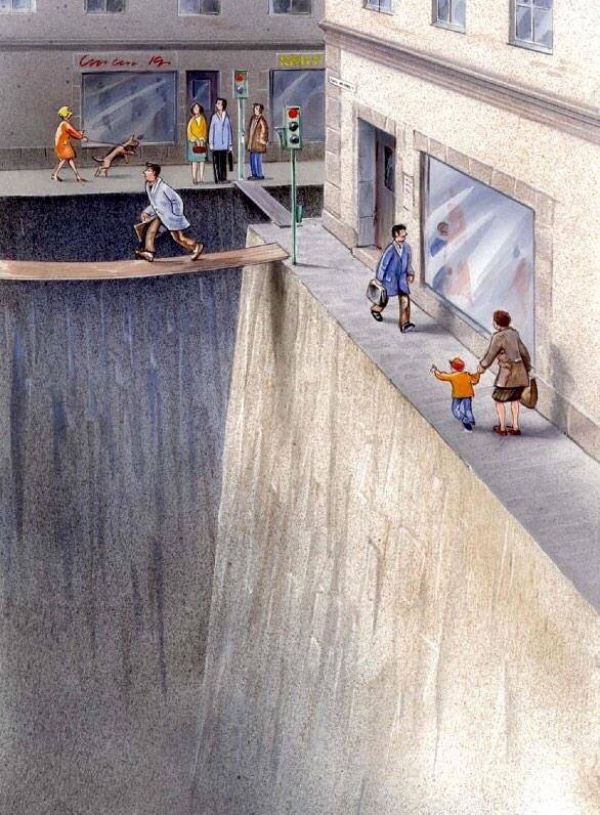

Indeed, this sort of single-use living zone essentially forces people to live online.

Doing almost *anything* requires them to drive somewhere, whether socialising or shopping or going to work or, God forbid, even just going for an evening stroll.

Doing almost *anything* requires them to drive somewhere, whether socialising or shopping or going to work or, God forbid, even just going for an evening stroll.

While you've got those vast commercial blocks of offices and shops which, at night, become eerily empty. A waste of electricity, too.

Our lives are sequestered by single-use zoning: community, happiness, civic pride & identity, they're all damaged by it.

Our lives are sequestered by single-use zoning: community, happiness, civic pride & identity, they're all damaged by it.

Of course, not everywhere needs to be mixed-use. Certain industries need their own space, while many people prefer to live in quieter, exclusively residential areas.

There will always be a place for single-use areas, which are both natural and imporant.

There will always be a place for single-use areas, which are both natural and imporant.

But that *thing* which makes certain towns and cities feel so deeply alive is, most likely, the quality of being mixed-use.

It would be hard to argue that our cities don't need more mixed-use urban spaces. We need them now, perhaps, more than ever.

It would be hard to argue that our cities don't need more mixed-use urban spaces. We need them now, perhaps, more than ever.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh