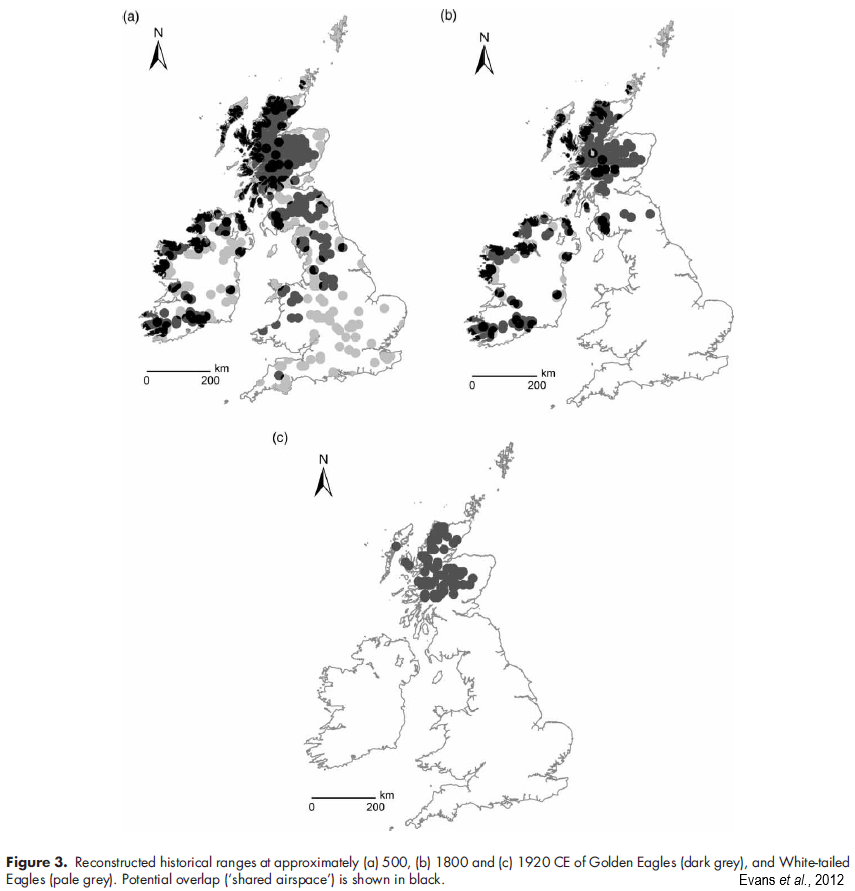

For #WorldAnimalDay I’ll talk about my research into Donegal’s Golden Eagles. Golden Eagles were once a resident breeding bird found throughout the upland and coastal areas of Ireland prior to their extinction due to persecution and habitat change around 1912. 1/18

They are Ireland’s second largest raptor, after white-tailed eagles. With a wingspan up to 212 cm, males weigh 3.7 kg whilst females 5.3 kg on average. They can live to 23 years and begin breeding at 4 years old. Their diet is mostly mammals or birds, both alive or scavenged 2/18

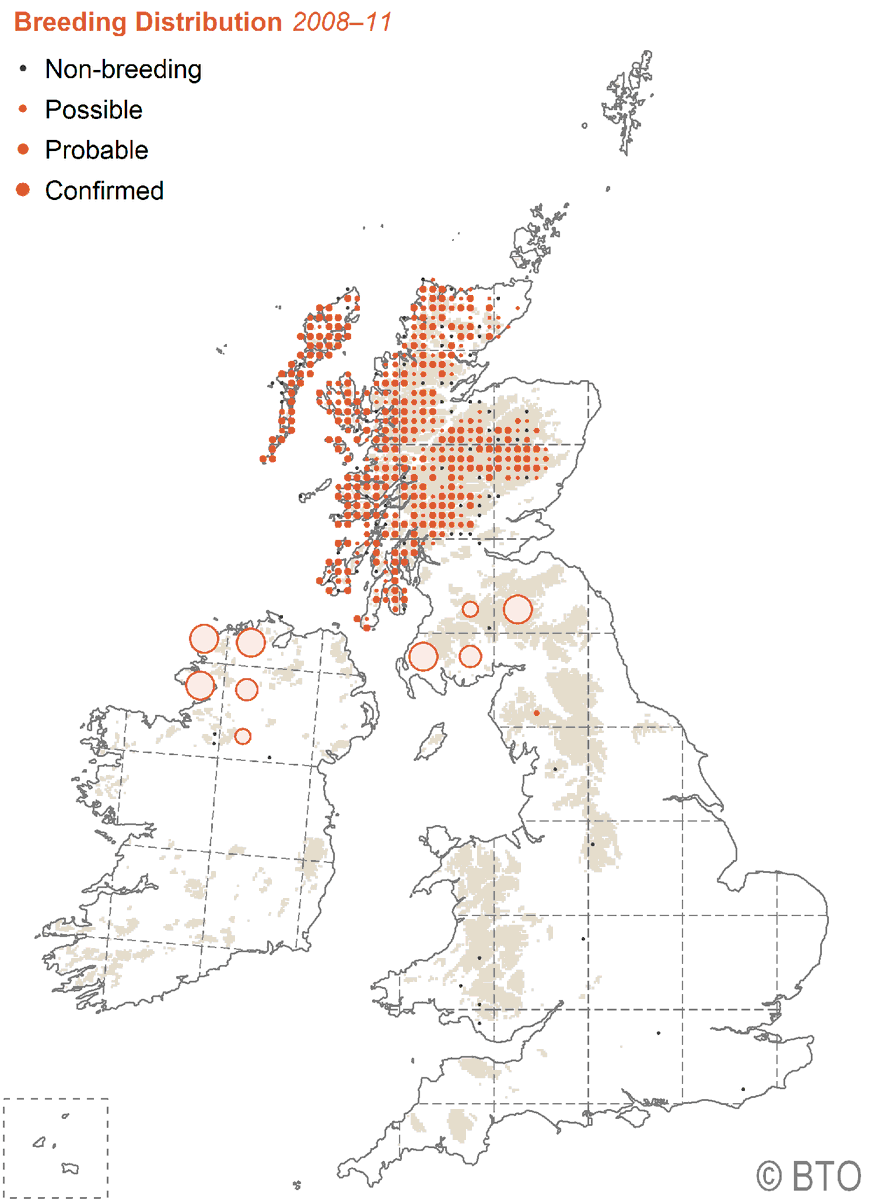

@eagle_trust carried out the first #reintroduction of chicks in 2001 with breeding attempts by reintroduced GEs recorded in 2005 and the first chick fledged successfully in 2007. In 2017, for the first time in over a century, an Irish-bred eagle successfully reared a chick3/18

However, GE have performed more poorly than pre-release productivity models projected. Productivity per breeding attempt was 0.625chicks (2005-2019, n = 32). 4/18

This low breeding performance could be linked with a suspected deterioration of available prey and upland habitat quality. Irish upland habitats have a long history of land-use change, including overgrazing and inappropriate burning. 5/18

Additionally, Irish Hare and Red Grouse, which form a vital component of eagle diets, have undergone long-term population declines across Ireland. 6/18

My MSc project aimed to assess upland habitat quality and prey availability in the reintroduced Golden eagle’s core range. I surveyed Cloghernagore Bog and Glenveagh National Park Special Area of Conservation between April and July 2018. 7/18

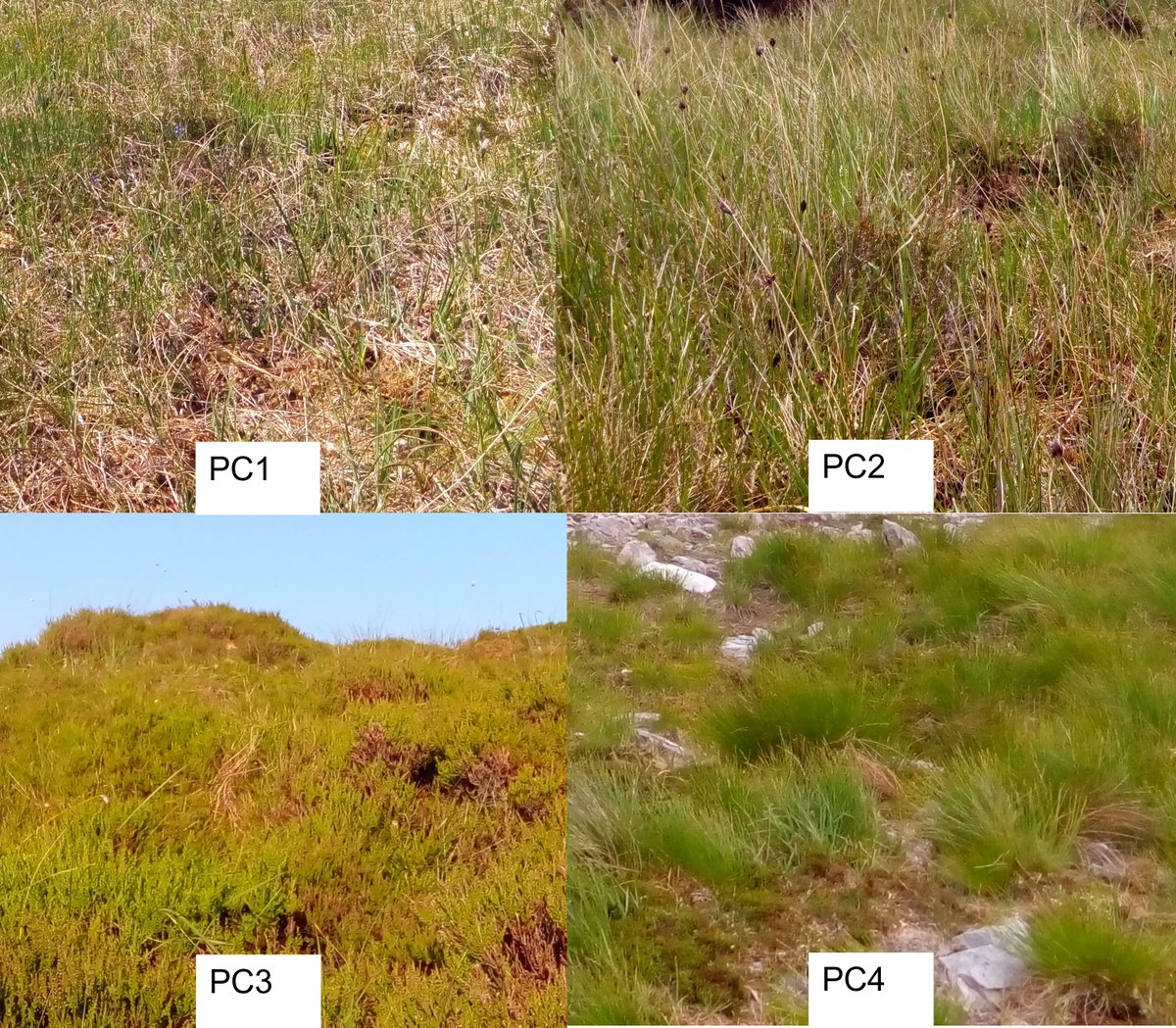

The area is characterised by a mosaic of uplands habitats. I used transects to record vegetation characteristics and field signs, such as droppings, tracks and feathers, of hare and grouse. Camera traps were used to find hare and grouse. 8/18

I classified the vegetation into four communities: 1-Short, open vegetation or bare ground where heather was absent 2-Tall tussocks of bogrush where Sphagnum spp. were absent 3-Heather where Purple moor-grass was absent and 4 Deergrass where Hares-tail cottongrass was absent.9/18

In over 44,000 videos, my camera traps had 126 wildlife detections, including 74 of red deer, but captured only 1 hare and 1 grouse. See if you can spot them below! 10/18

Ling heather, which is essential to red grouse for food and shelter and which hares show a preference for in upland areas, was significantly reduced/absent from areas with higher deer numbers. 11/18

My study found hare densities of 0.2 hares/km2, which was 94% lower than a wider regional density of 3.5 hares/km2 (McGowan2019). The density of territory holding male grouse was estimated at 1.7males/km2, 39% higher than 1.2 males/km2 reported during 2006/08 (Cummins2010). 12/18

The live-prey availability for golden eagles, in the form of hares and grouse, was calculated as 1.6 – 2.5 kg prey/km2/year. This is 73-83% less the 9.2 kg prey/km2/year required to maintain the viability of the Golden eagle population. 13/18

The abundance of live-prey for eagles can be reduced through overgrazing and competition with larger grazers. Frequent grazing and trampling by red deer results in the loss of ling heather and its replacement by grasses, sedges and rushes. 14/18

Irish hare require tall vegetation for shelter and new growth for food while Red grouse depend on a dense cover of ling heather of various ages for food and shelter. 15/18

Strategies which reduce grazing pressure from red deer could be implemented in areas of the SAC in order to encourage habitat recovery. Improving upland habitat quality would result in greater live prey abundance which could increase the breeding success of Golden eagles. 16/18

Indeed @Glenveagh_NP are now undertaking actions to restore habitats in the park, including planting native Scots pine, controlling invasive plants, erecting fences and controlling deer numbers across the park. 17/18

Thanks to @NeilReid81 @QUBbioscience, Ryan Wilson-Parr @IrishRaptorSG and Lorcan O’Toole @eagle_trust for their guidance in the project, and to the rangers @Glenveagh_NP @npwsBioData for fieldwork help. It was this project that led to my PhD, which I'll start on tomorrow. 18/18

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh