Shakespeare didn't invent his own stories and characters; he borrowed them.

Here's the source material for all 38 of his plays, in alphabetical order:

Here's the source material for all 38 of his plays, in alphabetical order:

1. All's Well That Ends Well (1602)

Based on the ninth tale of the third day in Giovanni Boccaccio’s masterpiece, the Decameron.

Completed in 1353, the Decameron is a collection of one hundred short stories told by friends over ten days during the Black Death.

Based on the ninth tale of the third day in Giovanni Boccaccio’s masterpiece, the Decameron.

Completed in 1353, the Decameron is a collection of one hundred short stories told by friends over ten days during the Black Death.

2. Antony and Cleopatra (1606)

Based on the Life of Marcus Antonius, from Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. It's a collection of 48 mini-biographies of important figures from Roman and Greek history, written in the 2nd century AD and translated into English by Thomas North in 1580.

Based on the Life of Marcus Antonius, from Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. It's a collection of 48 mini-biographies of important figures from Roman and Greek history, written in the 2nd century AD and translated into English by Thomas North in 1580.

3. As You Like It (1599)

Based on Thomas Lodge’s 1587 prose work Rosalynde Euphues Golden Legacie, which itself was inspired by the Medieval ballad The Tale of Gamelyn, from around 1350.

Based on Thomas Lodge’s 1587 prose work Rosalynde Euphues Golden Legacie, which itself was inspired by the Medieval ballad The Tale of Gamelyn, from around 1350.

4. The Comedy of Errors (1595)

A modern interpretation of The Brothers Menaechmus, written by the great Roman comedic playwright Plautus (254-184 BC). This play had been translated into English in 1594.

A modern interpretation of The Brothers Menaechmus, written by the great Roman comedic playwright Plautus (254-184 BC). This play had been translated into English in 1594.

5. Coriolanus (1607)

Based on the dramatically told Life of Coriolanus, again from North’s translation of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives.

Based on the dramatically told Life of Coriolanus, again from North’s translation of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives.

6. Cymbeline (1609)

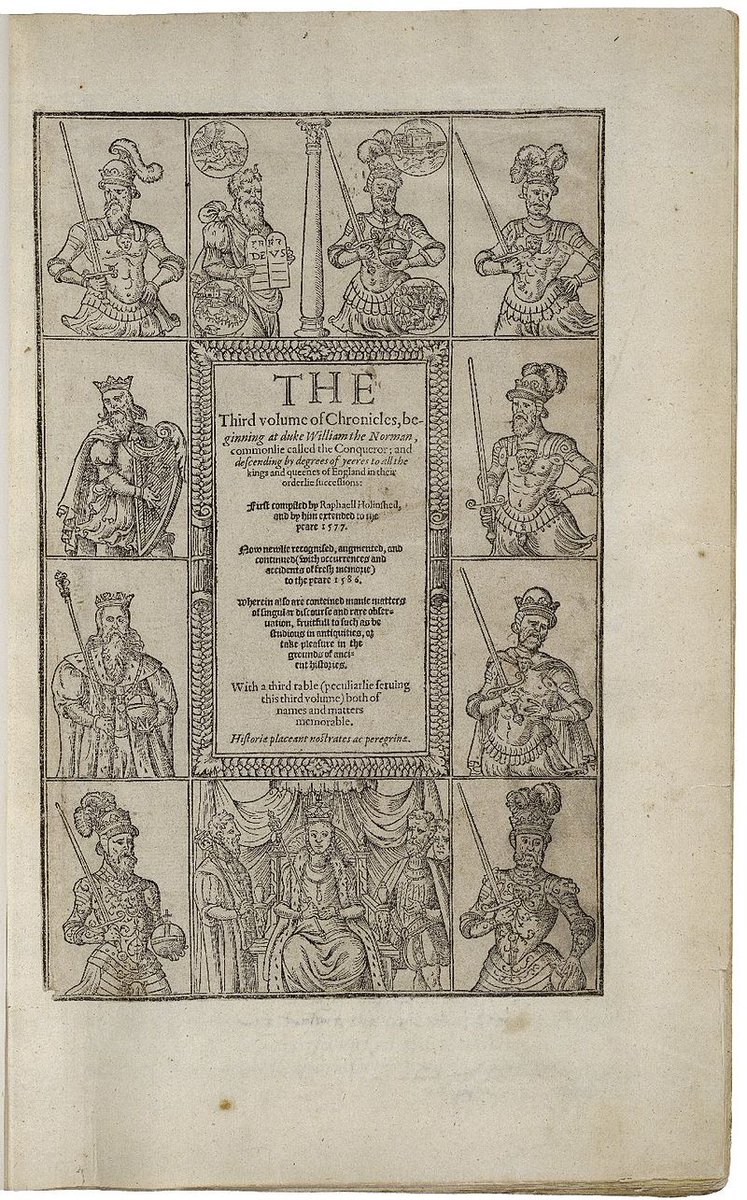

Inspired by myths from Celtic Legend, along with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain (1136) and Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577). Some plot elements are also lifted from Boccaccio’s Decameron.

Inspired by myths from Celtic Legend, along with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain (1136) and Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577). Some plot elements are also lifted from Boccaccio’s Decameron.

7. Hamlet (1600)

Comes from the Old Norse Saga of King Rolf Kraki.

This was incorporated into the Life of Amleth by the Danish writer Saxo Grammaticus (13th century), and from there to Francois de Belleforest’s Histoires Tragiques (1570).

Comes from the Old Norse Saga of King Rolf Kraki.

This was incorporated into the Life of Amleth by the Danish writer Saxo Grammaticus (13th century), and from there to Francois de Belleforest’s Histoires Tragiques (1570).

8. Henry IV, Parts I & II (1597)

As with all his English history plays, the primary source was Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles (1st ed. 1577, 2nd ed. 1587), though Holinshed’s work did take from Edward Hall’s The Union of the Two Illustrious Families of Lancaster and York (1548).

As with all his English history plays, the primary source was Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles (1st ed. 1577, 2nd ed. 1587), though Holinshed’s work did take from Edward Hall’s The Union of the Two Illustrious Families of Lancaster and York (1548).

9. Henry V (1598)

Holinshed’s Chronicles, again. This was, by the way, a comprehensive narrative history of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Another possible source was an anonymous Elizabethan play called The Famous Victories of Henry V (1594)

Holinshed’s Chronicles, again. This was, by the way, a comprehensive narrative history of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Another possible source was an anonymous Elizabethan play called The Famous Victories of Henry V (1594)

10. Henry VI, Parts I, II, & III (1590-91)

Based on specific parts from both Holinshed’s Chronicles and Hall’s The Union of the Two Illustrious Families of Lancaster and York.

Based on specific parts from both Holinshed’s Chronicles and Hall’s The Union of the Two Illustrious Families of Lancaster and York.

11. Henry VIII (1612)

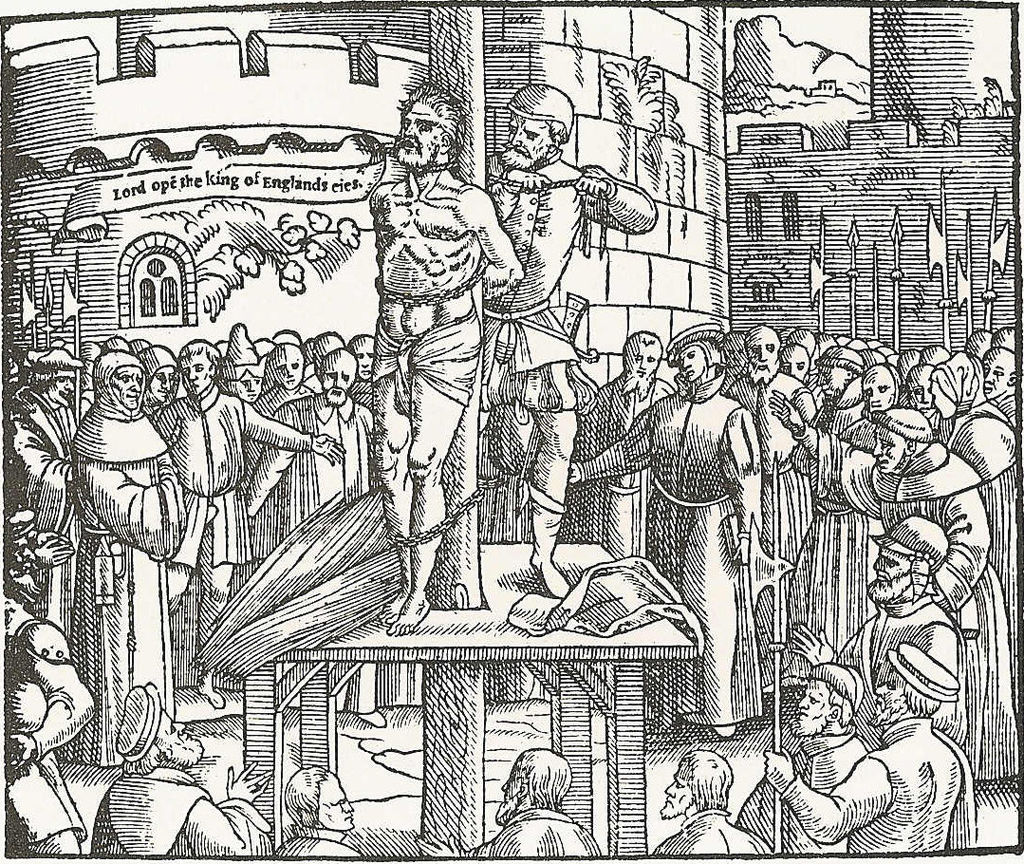

Holinshed’s Chronicles, and also Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, from 1570, a work of martyrology which detailed the suffering of Protestants under Catholicism.

Holinshed’s Chronicles, and also Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, from 1570, a work of martyrology which detailed the suffering of Protestants under Catholicism.

12. Julius Caesar (1599)

Based on North’s translation of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, though not just the Life of Julius Caesar. Some would say the Life of Brutus is more important, as Brutus is – truly – the protagonist of the play.

Based on North’s translation of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, though not just the Life of Julius Caesar. Some would say the Life of Brutus is more important, as Brutus is – truly – the protagonist of the play.

13. King John (1596)

Heavily based on George Peele’s 1589 play The Troublesome Reign of King John. That play itself draws on Holinshed’s Chronicles and Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.

Heavily based on George Peele’s 1589 play The Troublesome Reign of King John. That play itself draws on Holinshed’s Chronicles and Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.

14. King Lear (1605)

Several sources, primarily Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, via Holinshed’s Chronicles. Some elements taken from Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queen (1590) and Philip Sydney’s Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia (1580).

Several sources, primarily Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, via Holinshed’s Chronicles. Some elements taken from Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queen (1590) and Philip Sydney’s Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia (1580).

16. Macbeth (1605)

Partially inspired by the Daemonologie, a 1597 essay on ancient black magic by King James VI of Scotland. Also Hector Boece’s Historia Gentis Scotorum (1527), George Buchanan’s Rerum Scoticarum Historia (1582) and Holinshed’s Chronicles.

Partially inspired by the Daemonologie, a 1597 essay on ancient black magic by King James VI of Scotland. Also Hector Boece’s Historia Gentis Scotorum (1527), George Buchanan’s Rerum Scoticarum Historia (1582) and Holinshed’s Chronicles.

17. Measure for Measure (1604)

Based on The Story of Epitia from Cinthio’s Gli Hecatommithi (1565) and George Whetstone’s closet drama Promos and Cassandra (1578).

Based on The Story of Epitia from Cinthio’s Gli Hecatommithi (1565) and George Whetstone’s closet drama Promos and Cassandra (1578).

18. The Merchant of Venice (1596)

Takes plot elements from Giovanni Fiorentino’s Il Pecorone (1385), The Orator by Alexandre Sylvane (1596), and the Gesta Romanorum, a collection of Latin anecdotes and stories compiled in the 13th century.

Takes plot elements from Giovanni Fiorentino’s Il Pecorone (1385), The Orator by Alexandre Sylvane (1596), and the Gesta Romanorum, a collection of Latin anecdotes and stories compiled in the 13th century.

20. A Midsummer Night's Dream (1595)

Many inspirations: Edmund Spenser’s Epithalamion (1594), Aristophanes’ comedy The Birds (414 BC), Chaucer’s The Knight’s Tale (1400), Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 AD), and the German poem Der Busant (11th-13th century).

Many inspirations: Edmund Spenser’s Epithalamion (1594), Aristophanes’ comedy The Birds (414 BC), Chaucer’s The Knight’s Tale (1400), Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 AD), and the German poem Der Busant (11th-13th century).

21. Much Ado about Nothing (1598)

Partially based on The Novelle of Matteo Bandello (1550s), which followed the model of Boccaccio’s Decameron as a collection of short tales. A translation into French featured in Belleforest’s Histoires Tragiques (1583).

Partially based on The Novelle of Matteo Bandello (1550s), which followed the model of Boccaccio’s Decameron as a collection of short tales. A translation into French featured in Belleforest’s Histoires Tragiques (1583).

22. Othello (1604)

An adaption of Cinthio’s story A Moorish Captain, from his 1565 work Gli Hecatommithi. Perhaps also borrowed from One Thousand and One Nights and Gasparo Contarini’s The Commonwealth of Venice, translated into English in 1599.

An adaption of Cinthio’s story A Moorish Captain, from his 1565 work Gli Hecatommithi. Perhaps also borrowed from One Thousand and One Nights and Gasparo Contarini’s The Commonwealth of Venice, translated into English in 1599.

23. Pericles (1608)

Two main sources. John Gower’s poem Confessio Amantis (1393), and a prose version of that poem written by Lawrence Twine in 1576, entitled The Pattern of Painful Adventures.

Two main sources. John Gower’s poem Confessio Amantis (1393), and a prose version of that poem written by Lawrence Twine in 1576, entitled The Pattern of Painful Adventures.

26. Romeo and Juliet (1594)

Elements from Ovid and Xenophon’s Ephesiaca. Dante mentions Montagues and Capulets. Salernitano’s Il Novellino (1476), Da Porto’s History of Two Noble Lovers (1524), Bandello, and Arthur Brooke’s The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet (1562).

Elements from Ovid and Xenophon’s Ephesiaca. Dante mentions Montagues and Capulets. Salernitano’s Il Novellino (1476), Da Porto’s History of Two Noble Lovers (1524), Bandello, and Arthur Brooke’s The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet (1562).

27. The Taming of the Shrew (1593)

Many sources. One Thousand and One Nights again. Also Pontus de Huyter’s De Rebus Burgundicis (1584), Don Juan Manuel’s Tales of Count Lucanor (1335), Plautus’ Mostellaria, and more. There is also a strong folkloric influence.

Many sources. One Thousand and One Nights again. Also Pontus de Huyter’s De Rebus Burgundicis (1584), Don Juan Manuel’s Tales of Count Lucanor (1335), Plautus’ Mostellaria, and more. There is also a strong folkloric influence.

28. The Tempest (1611)

No primary source. Partially inspired by The Shipwreck, from Erasmus’ Colloquia Familaria (1518), Peter Martyr’s De Orbo Novo (1530), and William Strachey’s True Reportory (1610), an eye-witness account of a shipwreck.

No primary source. Partially inspired by The Shipwreck, from Erasmus’ Colloquia Familaria (1518), Peter Martyr’s De Orbo Novo (1530), and William Strachey’s True Reportory (1610), an eye-witness account of a shipwreck.

29. Timon of Athens (1607)

Based on the 28th novella of William Painter’s Palace of Pleasure (1558-1575), a multi-edition translation of short tales from Ancient Greek, Ancient Roman, French, and Italian sources.

Based on the 28th novella of William Painter’s Palace of Pleasure (1558-1575), a multi-edition translation of short tales from Ancient Greek, Ancient Roman, French, and Italian sources.

30. Titus Andronicus (1593)

Many sources, such as the Gesta Romanorum, Bandello, and Painter's Palace of Pleasure. Specific plot points taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita (26 BC), with Plutarch’s Lives – as ever – a source of names and ideas.

Many sources, such as the Gesta Romanorum, Bandello, and Painter's Palace of Pleasure. Specific plot points taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita (26 BC), with Plutarch’s Lives – as ever – a source of names and ideas.

31. Troilus and Cressida (1601)

Based most of all on Geoffrey Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde (1380s), the Troy Book by John Lydgate (15th century), and Recueil des Histoires de Troye, a French tale translated by William Caxton in 1464.

Based most of all on Geoffrey Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde (1380s), the Troy Book by John Lydgate (15th century), and Recueil des Histoires de Troye, a French tale translated by William Caxton in 1464.

32. Twelfth Night (1599)

Heavily based on The Deceived Ones, a 1531 Italian comedy. Once again, Bandello was another source. Also inspired by the actual Twelfth Night, a licentious Elizabeth folk festival.

Heavily based on The Deceived Ones, a 1531 Italian comedy. Once again, Bandello was another source. Also inspired by the actual Twelfth Night, a licentious Elizabeth folk festival.

33. The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1594)

Based on the Spanish romance The Seven Books of the Diana, written by Jorge de Montemayor in 1559 and translated into English in 1582. Other sources include Thomas Elyot’s The Boke Named the Governour (1531), based on the Decameron.

Based on the Spanish romance The Seven Books of the Diana, written by Jorge de Montemayor in 1559 and translated into English in 1582. Other sources include Thomas Elyot’s The Boke Named the Governour (1531), based on the Decameron.

Some observations...

1) Even the greatest playwright of all time borrowed his ideas, plot-lines, psychologies, and stories from other writers/historians.

Sometimes it was inspiration, sometimes it was a specific plot point, and (rarely) it was word-for-word quotation.

1) Even the greatest playwright of all time borrowed his ideas, plot-lines, psychologies, and stories from other writers/historians.

Sometimes it was inspiration, sometimes it was a specific plot point, and (rarely) it was word-for-word quotation.

2) However, Shakespeare did not simply imitate them.

He made colossal changes to the locations, narrative structures, characters, themes, timings, and arrangement of his sources.

They were the starting point, but he refined and perfected the dramatic potential he found.

He made colossal changes to the locations, narrative structures, characters, themes, timings, and arrangement of his sources.

They were the starting point, but he refined and perfected the dramatic potential he found.

3) Languages

We aren’t sure, but it seems probable that Shakespeare had a grasp of French and Italian. The possibilities afforded by even a basic grasp of other languages – in this case discovering new sources – are clear.

We aren’t sure, but it seems probable that Shakespeare had a grasp of French and Italian. The possibilities afforded by even a basic grasp of other languages – in this case discovering new sources – are clear.

4) Read More

Had Shakespeare not consulted everything from Roman comedies to Greek history to Celtic legend to Italian tales, he might not have produced these plays.

So – read more.

Had Shakespeare not consulted everything from Roman comedies to Greek history to Celtic legend to Italian tales, he might not have produced these plays.

So – read more.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh