This painting is over 100 years old.

It's by Zinaida Serebriakova, a wonderful painter with a fascinating life whose story is worth knowing...

It's by Zinaida Serebriakova, a wonderful painter with a fascinating life whose story is worth knowing...

Zinaida Lanceray was born in 1884 in the Russian Empire near Kharhov, modern-day Ukraine, to an artistic family.

Her father was a sculptor, her grandfather a famous architect, her uncle a painter.

She followed in their footsteps and studied art from a very young age.

Her father was a sculptor, her grandfather a famous architect, her uncle a painter.

She followed in their footsteps and studied art from a very young age.

She was tutored by the master Ilya Repin, from whom she learned about Realism, and later travelled to Europe, where she studied in France and Italy.

In her paintings of Paris from this time we can see that Serebriakova was also influenced by Post-Impressionism:

In her paintings of Paris from this time we can see that Serebriakova was also influenced by Post-Impressionism:

From a young age she was interested in the life of common people, of peasants and shepherds and fishermen, and of the agricultural world.

This was a theme she would return to time and time again throughout her life.

This was a theme she would return to time and time again throughout her life.

In 1905 Zinaida married Boris Serebriakov and, over the next decade, had four children.

This marked the beginning of her so-called "Happy Years", and we see another of the artistic themes which would dominate Serebriakova's career: family.

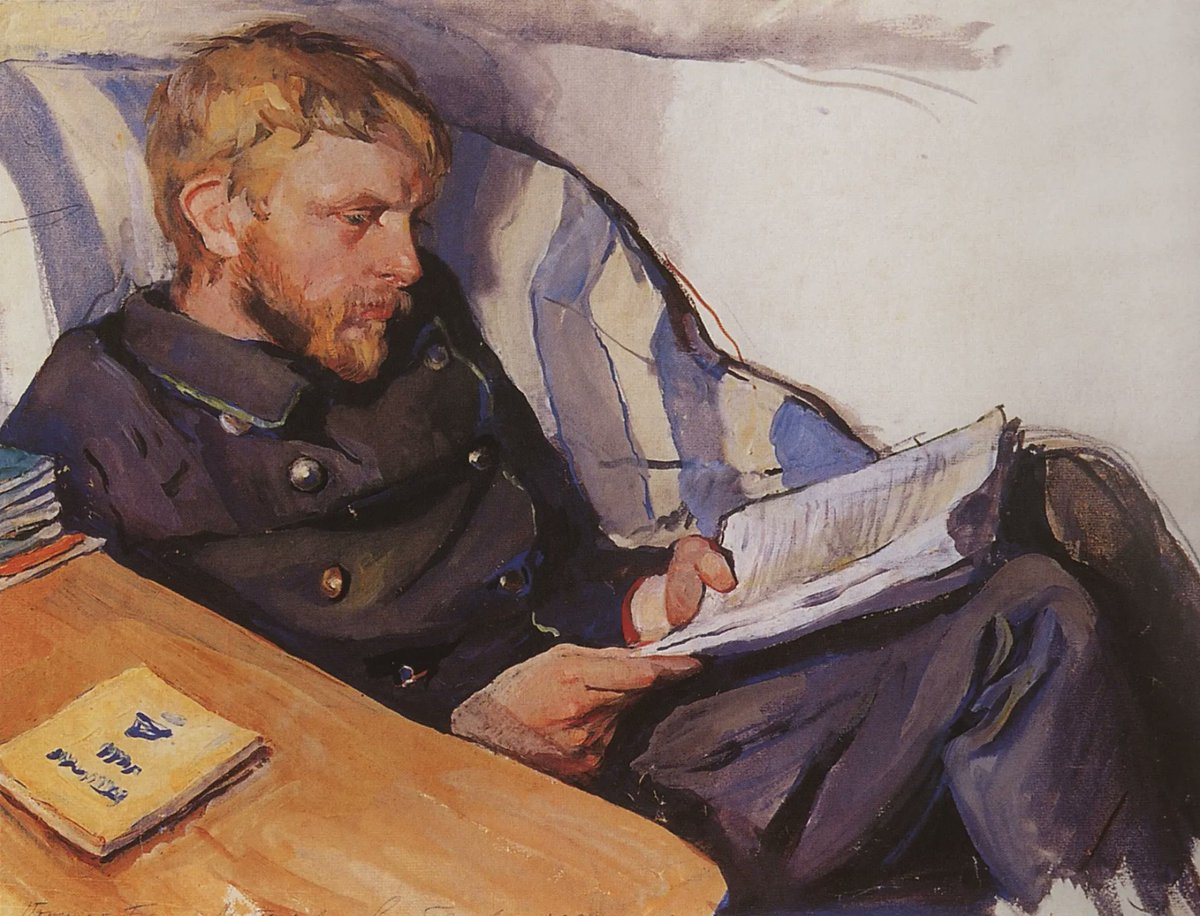

As in these portraits of her husband:

This marked the beginning of her so-called "Happy Years", and we see another of the artistic themes which would dominate Serebriakova's career: family.

As in these portraits of her husband:

Or, above all, of her children.

Whether at breakfast in the morning, with the wetnurse, or all together at dinner:

Whether at breakfast in the morning, with the wetnurse, or all together at dinner:

Serebriakova also painted self-portraits thoughout her life. With all their vivacity and honesty they might just be her best work.

As with her playful Self-Portrait as Pierrot, and another in the mirror with her beloved children:

As with her playful Self-Portrait as Pierrot, and another in the mirror with her beloved children:

Serebriakova sent her Self-Portrait At the Dressing Table to an exhibition in 1909 - it was received with critical acclaim. Even then her startlingly modern expression was a hit.

Along with Green Autumn and Peasant Girl, all were successfully auctioned.

Along with Green Autumn and Peasant Girl, all were successfully auctioned.

From 1914 onwards Serebriakova started to reach full artistic maturity, and certainly enjoyed the most successful years of her career with paintings such as Harvest (1915) and Bleaching Linen (1917).

She was all set to become part of the St. Petersburg Academy...

She was all set to become part of the St. Petersburg Academy...

But everything changed with the Russian Revolution of 1917.

The first problem was artistic: her personal style was no longer welcome in the world of avant-garde and Suprematist and Constructivist art favoured by Soviet Russia.

The first problem was artistic: her personal style was no longer welcome in the world of avant-garde and Suprematist and Constructivist art favoured by Soviet Russia.

And there was personal tragedy. Her beloved husband Boris was arrested in 1919 and died of typhus in jail.

Without his income and with declining commissions in the new regime, things took a downward turn.

Serebriakova was now a single mother with four children to raise:

Without his income and with declining commissions in the new regime, things took a downward turn.

Serebriakova was now a single mother with four children to raise:

They left the family estate - which had been plundered - and moved to an apartment in Petrograd.

She couldn't afford oil paints anymore, but Serebriakova continued to paint, taking an interest in ballet and theatre, which her daughter Ekaterina had taken up:

She couldn't afford oil paints anymore, but Serebriakova continued to paint, taking an interest in ballet and theatre, which her daughter Ekaterina had taken up:

She also continued to paint her children, perhaps with a streak of melancholy rather than the purer joy that had come before.

But something had to give...

But something had to give...

In 1924 she travelled to Paris, hoping to find commissions there and thus raise enough money to support her family.

Little could Serebriakova have known that travel would soon be restricted by the Soviet government. She was refused re-entry into Russia and became an exile.

Little could Serebriakova have known that travel would soon be restricted by the Soviet government. She was refused re-entry into Russia and became an exile.

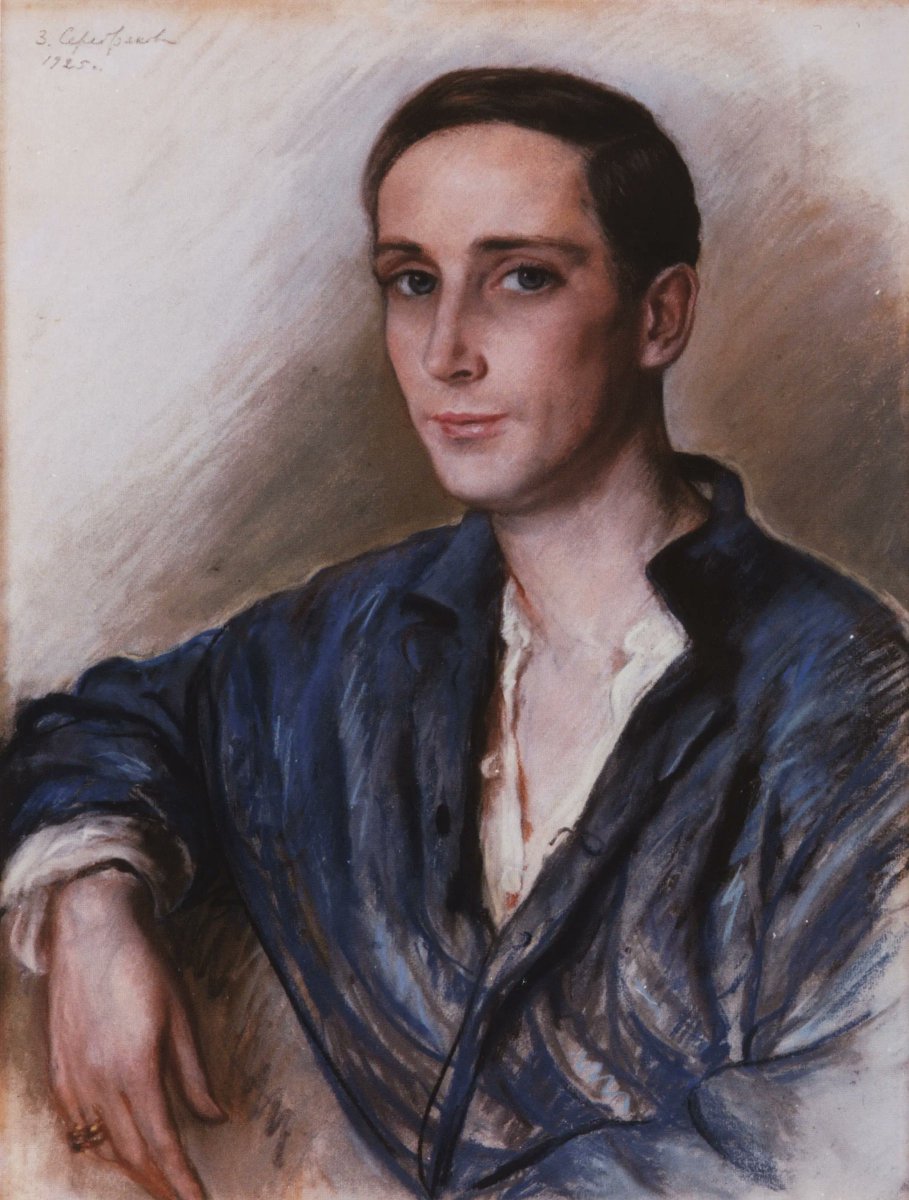

Serebriakova found both work and community in Paris with a group of Russian emigres and sent her earnings home. In 1926 her youngest son, Alexander, was allowed to join her, and in 1928 Ekaterina followed.

Here we see Serebkriakova in a 1930 self-portrait, looking perhaps a little more world-weary than in her earlier self-portraits:

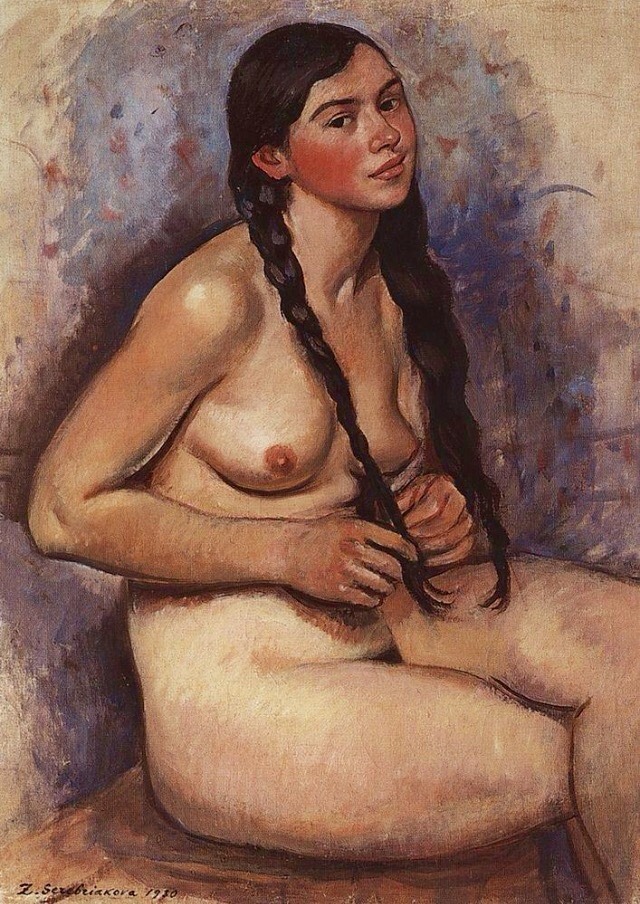

Serebriakova also visited Morocco several times, which left a deep impression on her.

There she found great delight in painting the ordinary people, as once she had done in Russia:

There she found great delight in painting the ordinary people, as once she had done in Russia:

And back in France Serebriakova continued to paint the common people, whether fishermen or bakers, alongside portraits for wealthier clients:

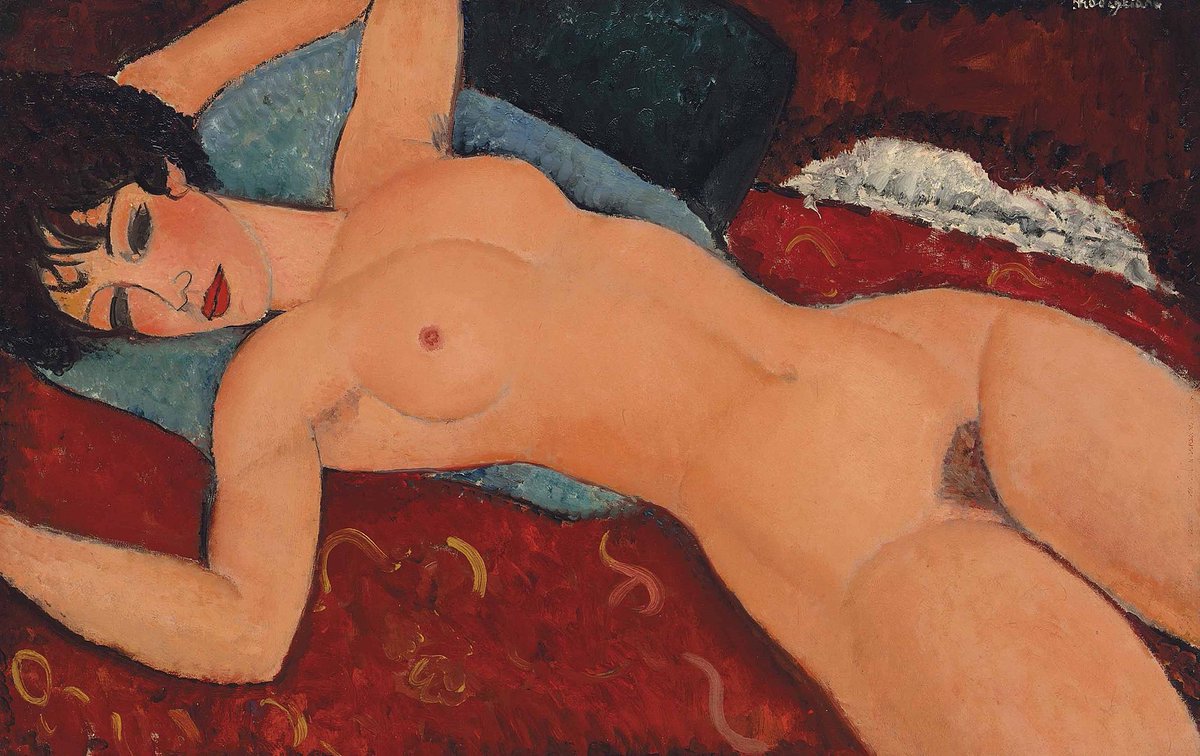

And in this era of her Parisian exile we see another theme emerge more fully in Serebriakova's work: the female nude.

It had long been there, as with Bather (1911), but during the 1920s and 1930s she painted them more frequently:

It had long been there, as with Bather (1911), but during the 1920s and 1930s she painted them more frequently:

During the Second World War, because of her nationality and frequent contact with her family in the USSR, Serebriakova became suspect in Nazi occupied Paris.

She was forced to renounce her Russian citizenship - and seemingly any hope of seeing the rest of her family again.

She was forced to renounce her Russian citizenship - and seemingly any hope of seeing the rest of her family again.

Zinaida Serebriakova's life and career had been long and volatile, affected by both World Wars and tarred with personal tragedy. And yet she had also become a successful and critically acclaimed artist.

Here we see a rather happier Self-Portrait from 1956:

Here we see a rather happier Self-Portrait from 1956:

But there was one great twist left. Thanks to Khrushchev’s Thaw, her daughter Tatiana was given permission to visit her mother in Paris, in 1960, and they were reunited after 36 years.

Zinaida Serebriakova was 76 at that point; Tatiana 50.

Zinaida Serebriakova was 76 at that point; Tatiana 50.

And in 1966 a vast exhibition of Serebriakova's work was held in Moscow; her work was a critical and commercial success.

Serebriakova had even travelled there - returning to Russian soil for the first time in nearly four decades - to witness it. Closure at last.

Serebriakova had even travelled there - returning to Russian soil for the first time in nearly four decades - to witness it. Closure at last.

Zinaida Serebriakova went back to Paris and died there the following year, in 1967, at the grand old age of 82.

Whether in depictions of her family, the common people, or herself, few painters have ever quite achieved such tenderness, intimacy, vivacity, and honesty.

Whether in depictions of her family, the common people, or herself, few painters have ever quite achieved such tenderness, intimacy, vivacity, and honesty.

I've written about Zinaida Serebriakova before in my free weekly newsletter, Areopagus.

It features seven short lessons every Friday, including art, architecture, rhetoric, and history.

Consider joining the 40k+ other subscribers here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

It features seven short lessons every Friday, including art, architecture, rhetoric, and history.

Consider joining the 40k+ other subscribers here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh