Monday thread 🧵

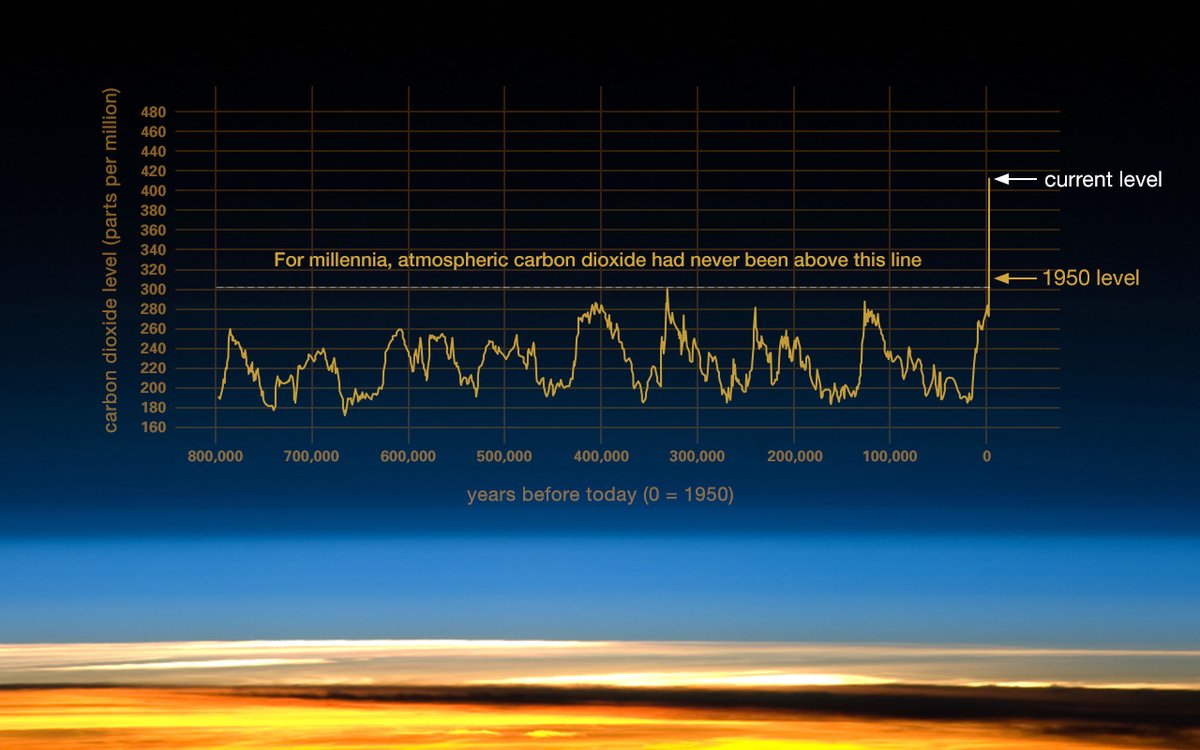

1. At this stage, I think most people are aware that the overwhelming scientific evidence indicates that humans have had a direct impact on the climate through the increased emissions of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane.

1. At this stage, I think most people are aware that the overwhelming scientific evidence indicates that humans have had a direct impact on the climate through the increased emissions of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane.

2. Over the last 40 years alone, the concentrations of both CO2 and methane in the atmosphere have increased significantly and have contributed to the observed rise in global air temperatures.

3. Peatlands have played a unique role in regulating the global climate over the last 10,000 years by sequestering (taking up) CO2 from the atmosphere, releasing methane (another carbon gas) back, and storing vast amounts of carbon in the process. Map: @greifswaldmoor

4. In natural peatlands (non-degraded), the amount of carbon taken up by peatland plants (as CO2 during photosynthesis) is much greater than the amount of CO2 and methane released back to the atmosphere.

5. This carbon imbalance occurs due to a persistently high water table that prevents the full decomposition of dead plant material. As a consequence, peat accumulates and so does the carbon contained in the peat.

6. Studies show that the average amount of carbon stored per year can be very small but when this is “repeated” over millennia, then the storage numbers become truly eye-popping.

7. Globally, there are an estimated 600 billion tonnes stored in peatlands and organic soils. New peatlands are still being found, so even this large value could be an underestimate. unep.org/resources/publ…

8. In Ireland, peatlands cover around 21% of the land surface. Remote-sensing work by @mapalljohn and colleagues have significantly improved our understanding of the extent of these wonderful ecosystems. tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

9. And recent work by @ProjectAuger estimates that Irish peatlands store a staggering 2.2 billion tonnes of carbon. However, less than 15% of Irish peatlands are in near-natural state, and the area actively sequestering carbon is likely to be even less.

epa.ie/publications/r…

epa.ie/publications/r…

10. So how is the peatland carbon store measured and how can we know how much carbon is gained or lost each year?

11. First you need to know how deep and how dense the peat is at the site. Ranging rods provide the depth and a special tool called an auger is used to take a sample for the calculation of density (done in a laboratory).

12. The carbon content of the peat must then be calculated. This value can vary considerably – lower in modified peats under grassland and greatest (over 50%) in natural sites.

13. Calculate the peatland area of interest and then put all the data in a pot, stir for 5 minutes, simmer and voila, you have a carbon store estimate for your site.

14. For measuring the carbon flux (i.e. movement of gas from one carbon pool to another), two approaches are widely used: static chambers and eddy covariance towers.

Chambers are essentially “boxes” that are placed over an area of interest and the change in gas concentration over a short time period is noted, as is the temperature in the chamber & soil, water level etc.

15. Measurements are repeated intensively throughout the day and year to capture all changes in weather, temperature etc. Statistical models are then combined with data from local weather stations and onsite data loggers to give an annual estimate for both CO2 and methane.

16. Recent developments include the gamechanging #LosGatos and #Licor portable analysers that now allow methane and CO2 calculations to be completely carried out in the field. Photos: @AitovaInNature @matts20000

17. Eddy covariance towers work at a much wider scale. Essentially, they consist of a scaffold & attached sensors that sample air from a large footprint, and determine the concentration of CO2 & methane within that sample. They operate 24/7/365. Photos: @matts20000 @MValmier

18. Unfortunately, the vast majority of Irish peatlands have been drained, degraded or modified to some extent. Under such conditions, the water table drops deeply, the peat is oxidised and CO2 emissions increase considerable.

19. An example of the negative effects of peatland drainage: the Holme Post was inserted into drained peat in East Anglia in the 1800s, with the top level with the peat surface. Almost 200 years later, the peat surface has dropped considerable due to subsidence and oxidation.

20. In 2013, we estimated that Irish peatlands were a net source of 3 million tonnes of carbon per year to the atmosphere (or 11 million tonnes CO2 per year).

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

21. Irish peatlands are a large carbon source and in the threads over the coming week, I’ll take a deeper dive into the different land uses that contribute to this and highlight actions that we can do to plug these losses. 🙏

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh