Tuesday 🧵

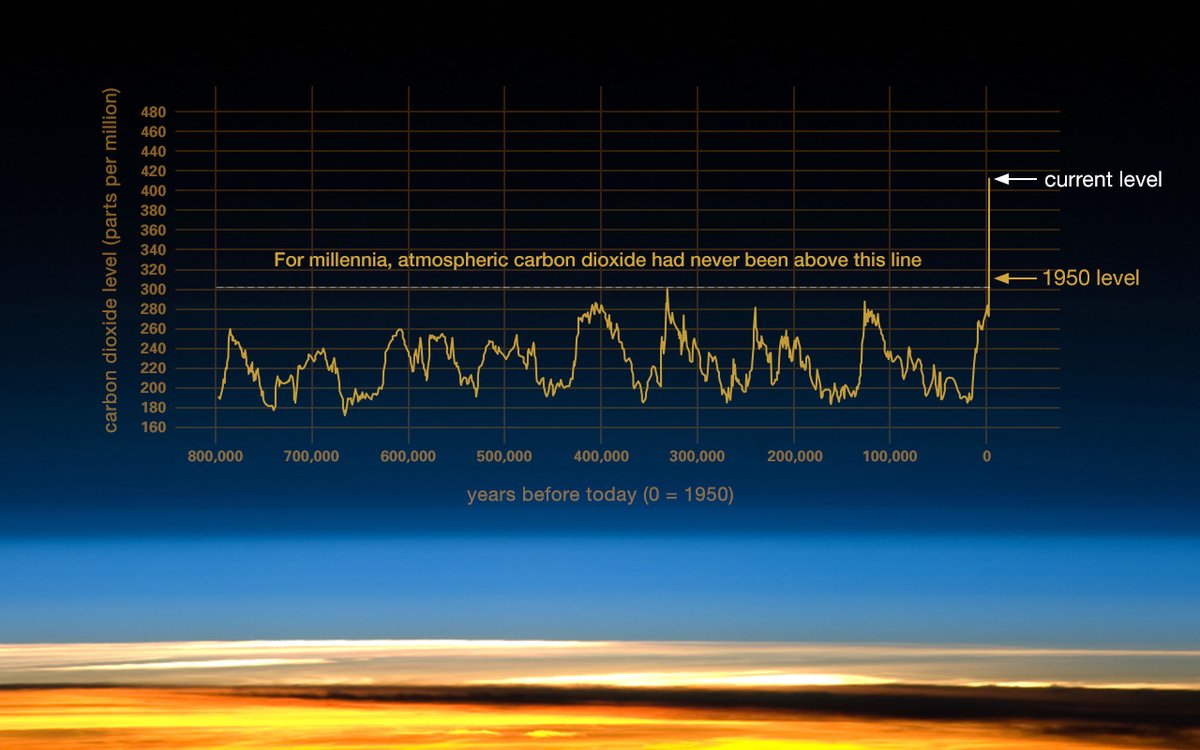

1. Today, I want to talk about carbon cycling in natural peatlands, as these ecosystems provide the baseline against which we assess damaged sites & evaluate restoration success. Plus, they act as the “canary-in-the-mine” for ongoing & future climate change.

1. Today, I want to talk about carbon cycling in natural peatlands, as these ecosystems provide the baseline against which we assess damaged sites & evaluate restoration success. Plus, they act as the “canary-in-the-mine” for ongoing & future climate change.

2. A natural peatland is undamaged, drained or modified and is characterised by a persistently high water table that ensures that more carbon goes into the system than goes out. The old adage that a wet bog is a good bog holds true here.

https://twitter.com/queenofpeat/status/1580994782649720833

3. In Ireland, very little (if any) of our peatlands can be considered natural. Instead, we use the terms near-natural and near-intact to accept the fact that all our sites have been modified to some extent.

4. Our near-natural peatlands include areas of Atlantic blanket bogs, mountain blanket bogs, raised bogs and a small amount of fens but differ in their carbon dynamics, e.g. nutrient-rich fens produce much greater methane emissions than nutrient poor bogs.

5. Even within a single site, the exchange of greenhouse gases between the peatland and the atmosphere can vary considerably both over time (HOT-TIMES: day, season, years) and spatially (HOT-SPOTS: vegetation community, water level, aerenchyma plants).

6. In general, the wetter areas within a site are likely to be bigger carbon sinks than “drier” hummocks for example.

7. Although conversely, wetter areas exhibit greater methane emissions, especially pools colonised by bog-bean (Menyanthes trifoliata) for example.

8. Some peatland plants, such as bog-cotton have specialised tissues called aerenchyma that are designed to passively move oxygen to the submerged roots but also allow methane to move back up through the plant to the atmosphere.

https://twitter.com/queenofpeat/status/1339298289951322116

9. Plants such as Typha latifolia take this process one step further and actively drive (through pressure gradients) oxygen down to the roots and methane up to the atmosphere.

10. In addition to sequestering CO2 and emitting methane, natural peatlands also lose some carbon in the water (known as dissolved organic carbon or DOC).

11. In most years, natural sites are net carbon sinks and are resilient to short periods of drought due to the presence of Sphagnum mosses that are able to hold considerable volumes of water and prevent the bog drying out and releasing CO2.

12. We are fortunate in Ireland to have long-term (10 years) carbon data from a near-natural blanket bog at Glencar, Co. Kerry. For the period of the study, the site was a sink for carbon of around 30 g carbon per m2 per year.

13. As I mentioned in yesterday’s thread, this small amount, when repeated over 1000s of years, produces huge carbon stores that can be rapidly lost when the site is drained or damaged.

14. Carbon monitoring is currently ongoing at Clara bog where @matts20000 and @ShaneRegan34 and colleagues are also determining the extent of carbon gains or losses and investigating what drives this exchange at this site.

15. The recent @ProjectAuger report estimates that near-natural peatlands hold around a quarter of the 2.2 billion tonnes of carbon held in Irish peatlands.

epa.ie/publications/r…

epa.ie/publications/r…

16. Therefore, it is critically important that we ensure that these sites remain wet and are adequately protected so that they can continue to store their carbon for another 10,000 years.

17. Tomorrow, I will talk about carbon and peat extraction. Buckle up, cos the ride is about to get bumpy.

Photos: @flo_renouwilson

Photo: @matts20000

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh