This gigantic sculpture, named after and intended to embody Italy's Apennine Mountains, was commissioned by Francesco de Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, in 1579.

Its creator was the Flemish sculptor Giambologna (more on him later) who finished the Colossus in 1580.

Its creator was the Flemish sculptor Giambologna (more on him later) who finished the Colossus in 1580.

The Medicis were a rich and influential banking family who left their mark all over Florence and, indeed, Italy.

They produced four popes and two French Queens, while ruling Florence & Tuscany and funding the work of Botticelli, Leonardo, and countless other artists.

They produced four popes and two French Queens, while ruling Florence & Tuscany and funding the work of Botticelli, Leonardo, and countless other artists.

Francesco de Medici had a large villa built for himself and his mistress (later wife) Bianca Cappello in 1569.

With all his political power, wealth, and artistic patronage, Francesco wanted to make a statement. Who better than the finest sculptor of the age, Giambologna?

With all his political power, wealth, and artistic patronage, Francesco wanted to make a statement. Who better than the finest sculptor of the age, Giambologna?

And so, hidden away in the vast gardens of the villa, Giambologna got to work on a sculpture intended to represent Italy's great Apennine mountains.

An allegory also, perhaps, for how Francesco viewed the Medici family: a powerful force at the heart of Italian affairs?

An allegory also, perhaps, for how Francesco viewed the Medici family: a powerful force at the heart of Italian affairs?

There's no clear mythological origin for the Colossus, though some have speculated that Giambologna was inspired by passages about Atlas from the works of Virgil and Ovid.

He is nearly forty feet tall, made from stone and plaster, with stylised moss and stalactites on his body.

He is nearly forty feet tall, made from stone and plaster, with stylised moss and stalactites on his body.

The Colossus indeed looks like a cross between man and mountain, like a living creature coming out of the rocks.

And so it was placed above a pond & surrounded by trees. The Colossus is crushing a sea monster with his hand, from which pours a fountain.

And so it was placed above a pond & surrounded by trees. The Colossus is crushing a sea monster with his hand, from which pours a fountain.

It gets even more ingenious. The Colossus was filled with a series of pipes which allowed water to trickle out from his body, as though he were sweating.

In winter this caused him to be covered in icicles.

In winter this caused him to be covered in icicles.

And *inside* the Colossus are several rooms or grottos, covered with mosaics and frescoes.

It shows the wealth of the Medici Family that they could afford to create such gigantic, almost frivolous works of art for their own private purposes.

It shows the wealth of the Medici Family that they could afford to create such gigantic, almost frivolous works of art for their own private purposes.

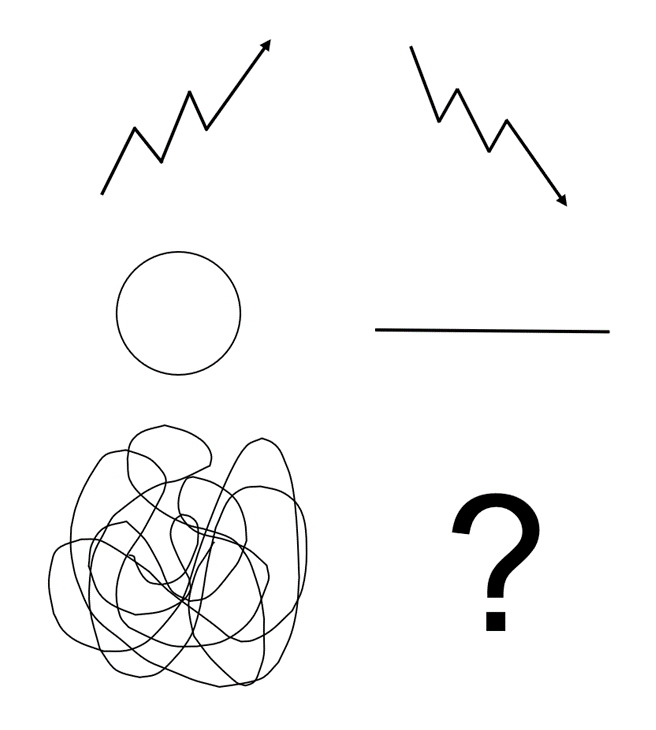

Here is a plan of the inside of the Colossus.

In the lower half was a shrine or sanctuary, and in the upper half was a space large enough for a small orchestra and audience.

Giambologna had achieved something truly spectacular.

In the lower half was a shrine or sanctuary, and in the upper half was a space large enough for a small orchestra and audience.

Giambologna had achieved something truly spectacular.

Franceso liked to fish in the lake from the chamber in the head of the Colossus, which was lit with fire at night. This would cause his eyes to glow red and smoke to billow from his nostrils.

And here is the shrine in the belly of the beast:

And here is the shrine in the belly of the beast:

Franceso de Medici died in 1587 and his Villa di Pratolino fell into disrepair and disuse: the Colossus suffered a similar fate.

It was altered, renovated, and restored several times over the centuries, including the addition of this dragon on his back in 1690:

It was altered, renovated, and restored several times over the centuries, including the addition of this dragon on his back in 1690:

So that's the Colossus. As for Giambologna, the sculptor, he was actually a Flemish man with the name of Jehan Boulongne (1529-1608).

But, given his success and popularity in Italy, he became known as Giovanni Bologna or Giambologna.

But, given his success and popularity in Italy, he became known as Giovanni Bologna or Giambologna.

He was a prolific master who worked in both bronze and stone, producing sculptures large or small on many different themes.

Such as Neptune, made to crown the Fountain of Neptune in Bologna in 1567, harking back to the heroic nudes of Ancient Greek & Roman sculpture:

Such as Neptune, made to crown the Fountain of Neptune in Bologna in 1567, harking back to the heroic nudes of Ancient Greek & Roman sculpture:

He was patronised, as many artists were, by the Medici Family.

And for them he created "Florence Triumphant Over Pisa" in 1566, a direct allegory for the power and success of the Medicis and their native city.

A reminder of how art also serves political ends:

And for them he created "Florence Triumphant Over Pisa" in 1566, a direct allegory for the power and success of the Medicis and their native city.

A reminder of how art also serves political ends:

Giambologna is regarded as the last great Renaissance sculptor and as a master of Mannerism. But what the hell is that?

Mannerism was the period of Renaissance art that immediately followed the High Renaissance: the age of Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

Mannerism was the period of Renaissance art that immediately followed the High Renaissance: the age of Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

See, the Renaissance caused trouble for artists. Leonardo and co had achieved supreme harmony and grace. They had mastered perspective, composition, and form.

Art had been perfected. What was there left to do?

Art had been perfected. What was there left to do?

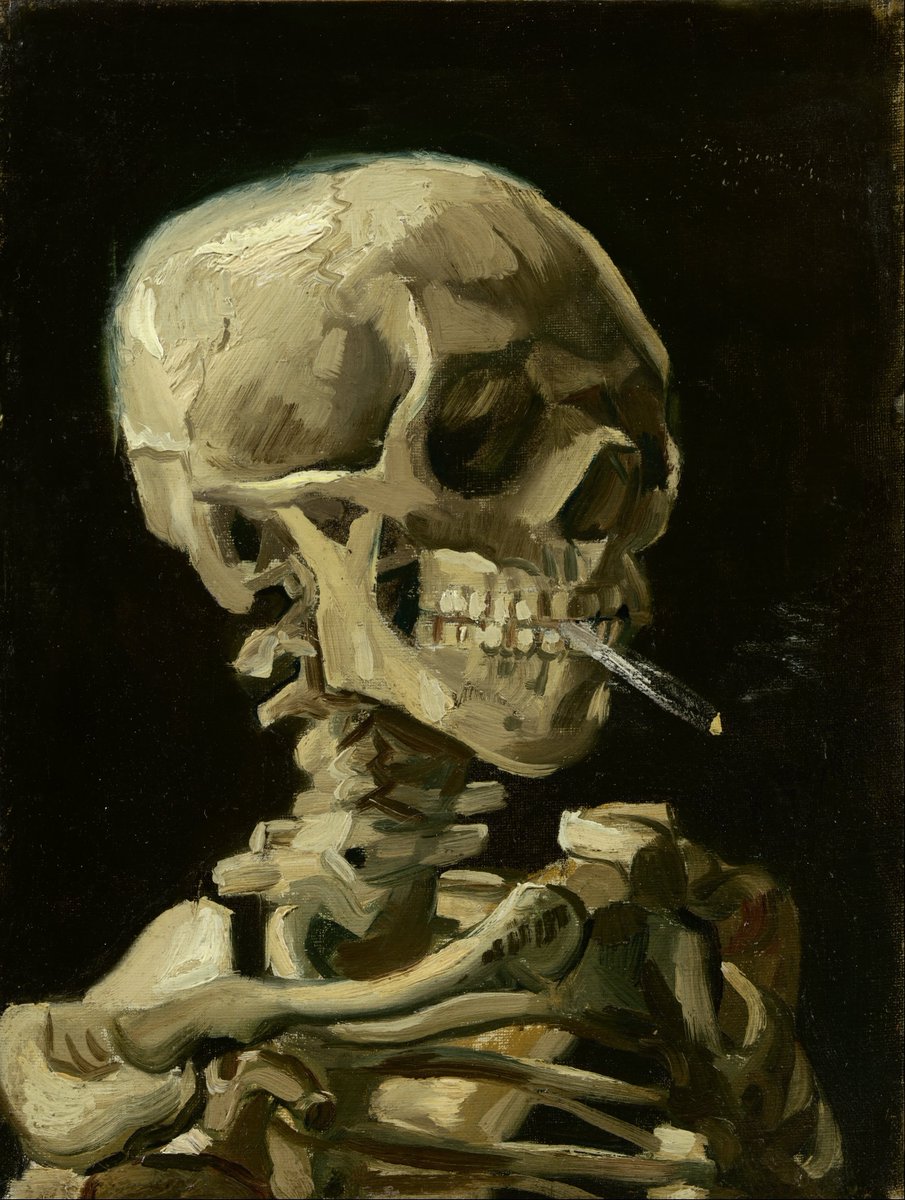

Mannerism rose in the 1520s as a struggle against the harmony of the High Renaissance, reaching into artificiality, instability, colour, and drama to find *something else* the masters had not achieved.

Hence Parmigianino's Madonna with her superhumanly elongated form, in 1540:

Hence Parmigianino's Madonna with her superhumanly elongated form, in 1540:

Just compare Leonardo da Vinci's famous Last Supper (1498) with the Last Supper of Tintoretto (1592)

One is balanced, harmonious, mellow, and composed; the other is vibrant, colourful, dramatic, and quite wild by comparison.

One is balanced, harmonious, mellow, and composed; the other is vibrant, colourful, dramatic, and quite wild by comparison.

The founding work of Mannerist sculpture was, strangely, an ancient statue.

Laocoon of Troy, created in the 2nd century B.C., was unearthed in Rome in 1506. Soon enough it had captured the imagination of young artists with its drama, discordance, and expressiveness:

Laocoon of Troy, created in the 2nd century B.C., was unearthed in Rome in 1506. Soon enough it had captured the imagination of young artists with its drama, discordance, and expressiveness:

Now compare Giambologna's Abduction of a Sabine Woman with Michelangelo's David. Notice the different in postures.

One is calm and graceful. This is *before* the drama. A moment of elegance.

The other is strained, twisted, and violent: this *is* the action; a moment of drama.

One is calm and graceful. This is *before* the drama. A moment of elegance.

The other is strained, twisted, and violent: this *is* the action; a moment of drama.

The pose of a sculpture, seemingly minor, reveals much about what the sculptor was trying to convey, even when a similar scene was being shown.

That's where you can really see the difference between sculptures of the High Renaissance and Mannerism.

Both of these are Hercules:

That's where you can really see the difference between sculptures of the High Renaissance and Mannerism.

Both of these are Hercules:

So the Apennine Colossus captures Mannerism rather well.

Unlike the grace of the High Renaissance, this was a bold, dramatic, extravagant, slightly wild sculpture with a strained and expressive pose.

Not to mention a statement about the wealth and power of the Medici Family.

Unlike the grace of the High Renaissance, this was a bold, dramatic, extravagant, slightly wild sculpture with a strained and expressive pose.

Not to mention a statement about the wealth and power of the Medici Family.

So that is the story of the Apennine Colossus, through which we can see the history of the Medici Family and the transition from High Renaissance to Mannerism in art.

But, at the end of the day, it's a captivating and extraordinary sculpture; that's what truly matters.

But, at the end of the day, it's a captivating and extraordinary sculpture; that's what truly matters.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh