The fragrance of sandalwood: A history of the Mysore Sandal Soap

How Sri Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV and his Dewan, Sir M. Visvesvaraya, established the century-old legacy of this soap brand, which was later elevated to new heights by Sosale Garalapuri Shastry.

How Sri Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV and his Dewan, Sir M. Visvesvaraya, established the century-old legacy of this soap brand, which was later elevated to new heights by Sosale Garalapuri Shastry.

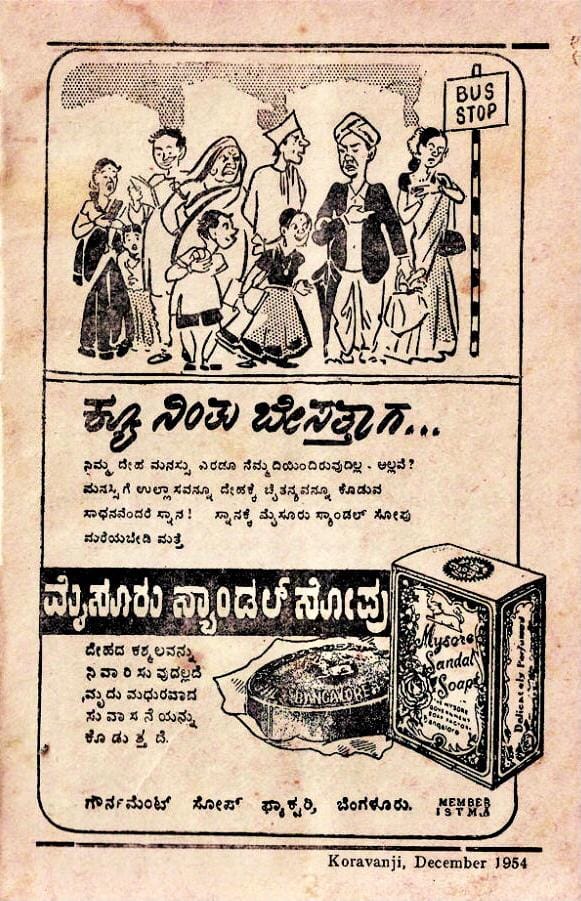

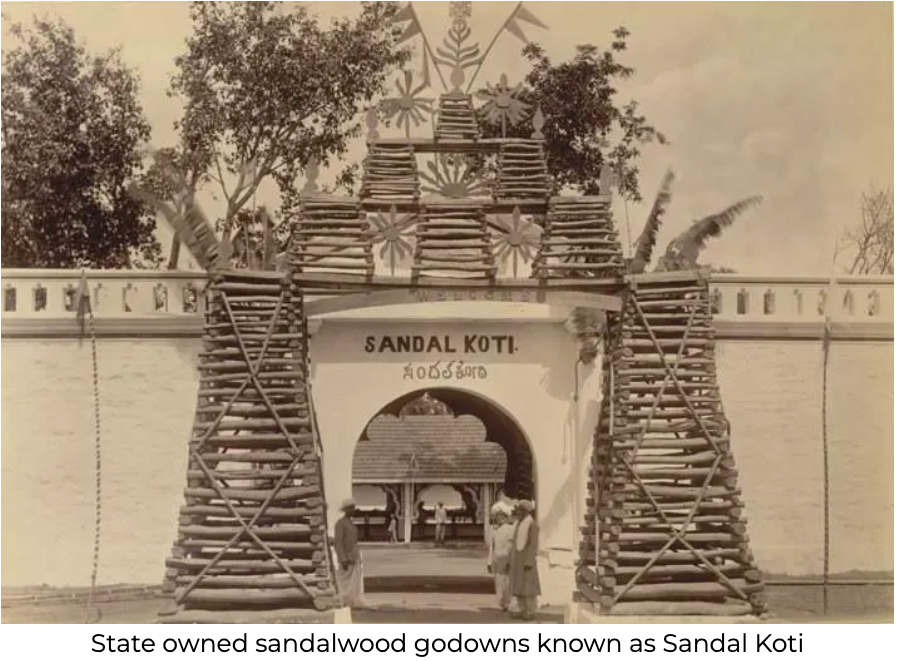

It all began somewhere in May 1916, during the First World War. At the time, Mysore was the world's largest producer of sandalwood.

Mysore would export the majority of sandalwood to Europe. But, due to the chaos of the world war, the city could not export the sandalwood.

Mysore would export the majority of sandalwood to Europe. But, due to the chaos of the world war, the city could not export the sandalwood.

In 1918, the Maharaja received a rare set of sandalwood oil soaps. This inspired him to produce similar soaps for the public.

To take things further, he asked Sir Visvesvaraya to make arrangements for soap-making experiments at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc).

To take things further, he asked Sir Visvesvaraya to make arrangements for soap-making experiments at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc).

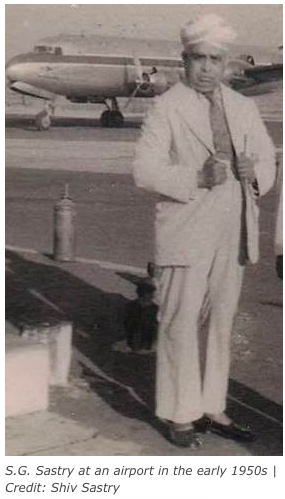

There, he discovered the brilliant chemist Sosale Garalapuri Shastry and sent him to England to hone his soap-making skills.

The diligent scientist, fondly remembered by many as Soap Shastry, was instrumental in realizing Visveswaraya's dream.

The diligent scientist, fondly remembered by many as Soap Shastry, was instrumental in realizing Visveswaraya's dream.

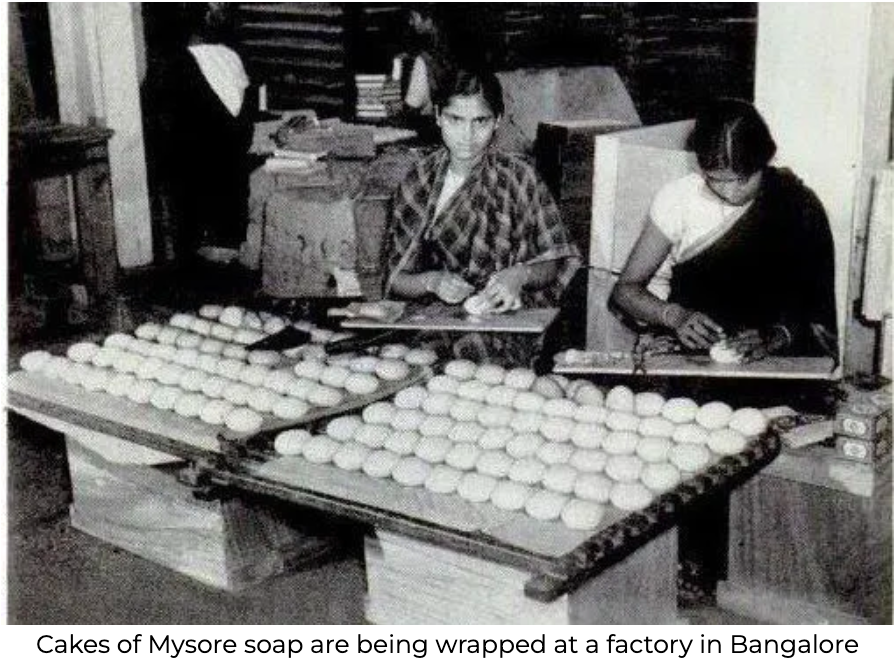

The first government soap factory was set up near K R Circle in Bengaluru to manufacture sandal soap. In 1918, this technique of using sandalwood oil for making soaps was standardized.

In the same year, another factory for distilling oil from sandalwood was set up in Mysore.

In the same year, another factory for distilling oil from sandalwood was set up in Mysore.

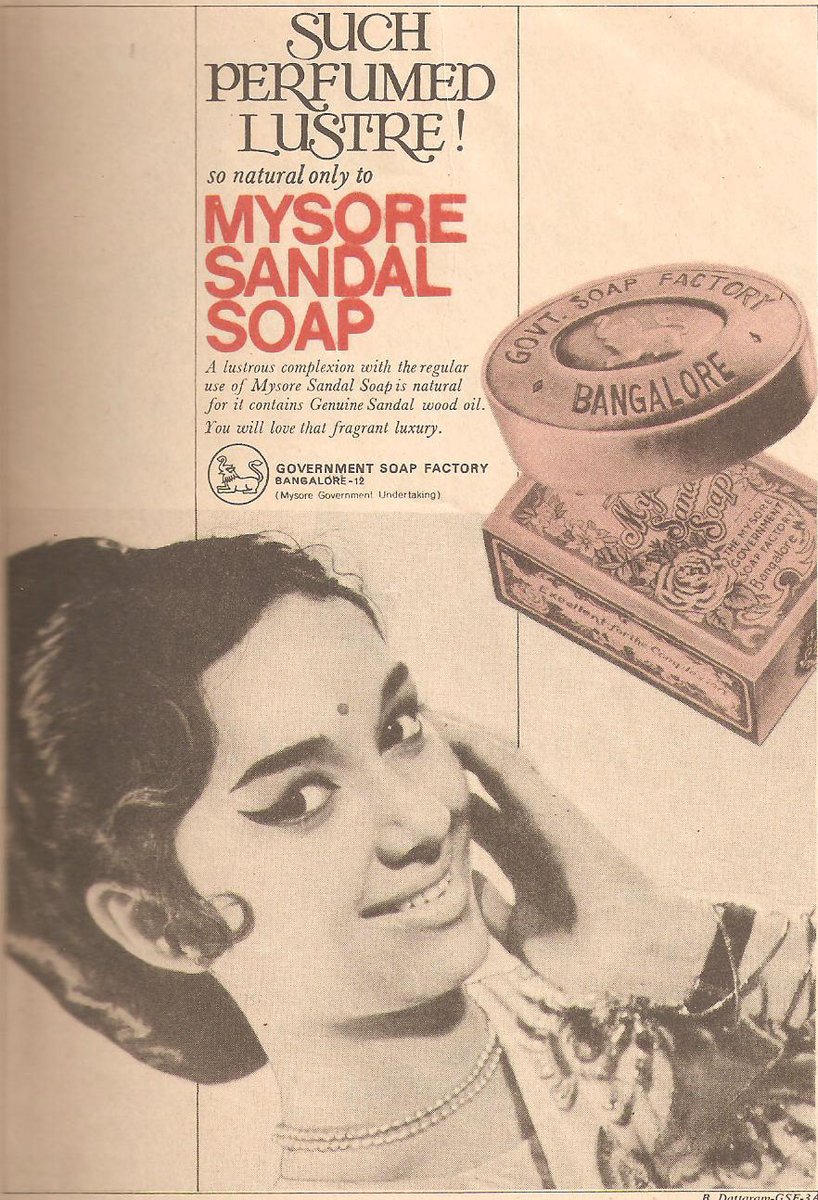

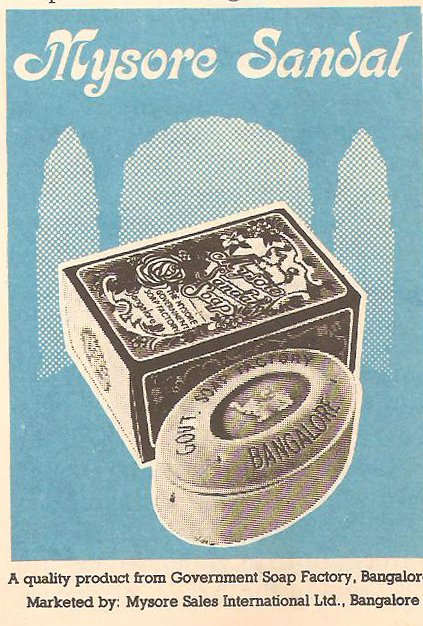

Sosale Garalapuri Shastry worked on the soap's culturally significant packaging as well.

As the logo for the factory, he chose Sharaba, a legendary creature with the body of a lion and the head of an elephant.

As the logo for the factory, he chose Sharaba, a legendary creature with the body of a lion and the head of an elephant.

The cover also had a special message, ‘Srigandhada Tavarininda’ ( from the maternal home of sandalwood’) printed on all the soapboxes.

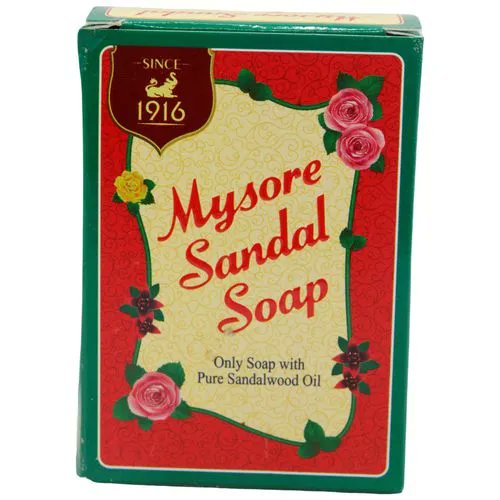

In addition, he designed a rectangular container with floral patterns and distinct hues. This container resembled a jewelry box.

In addition, he designed a rectangular container with floral patterns and distinct hues. This container resembled a jewelry box.

In 2006, the soap received a Geographical Indicator (GI) label, which means that only KSDL soap has the right to call itself "Mysore Sandalwood" soap.

If Boroline is a Bengali’s best friend, the Mysore sandal soap is definitely an integral part of a Kannadiga’s identity.

If Boroline is a Bengali’s best friend, the Mysore sandal soap is definitely an integral part of a Kannadiga’s identity.

Due to this near-monopolistic presence in the market for sandalwood bathing soaps, KSDL has also become one of Karnataka’s few public-sector enterprises that turns consistent profits.

In fact, the company registered its highest gross sales turnover (of ₹476 crore) in 2015-16.

In fact, the company registered its highest gross sales turnover (of ₹476 crore) in 2015-16.

The company has also successfully branched out into other soaps, incense sticks, essential oils, hand washes, and talcum powder, etc.

Nonetheless, the Mysore Sandal Soap remains the company’s flagship product, the only soap in the world made from 100% pure sandalwood oil.

Nonetheless, the Mysore Sandal Soap remains the company’s flagship product, the only soap in the world made from 100% pure sandalwood oil.

References:

(i) History Of Mysore Sandal Soap by Gijo Vijayan

(ii) Mysore Sandal Soap: A Maharaja’s Gift ~ Live History India

(iii) This sandalwood soap traces its origins back to WW1 (The Print)

(iv) The Fascinating History of Mysore Sandal Soap ~ The Better India

(i) History Of Mysore Sandal Soap by Gijo Vijayan

(ii) Mysore Sandal Soap: A Maharaja’s Gift ~ Live History India

(iii) This sandalwood soap traces its origins back to WW1 (The Print)

(iv) The Fascinating History of Mysore Sandal Soap ~ The Better India

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh