Analysing the architecture of the Harry Potter films:

(and why fictional buildings look the way they do)

(and why fictional buildings look the way they do)

Number 4 Privet Drive is a real house in Bracknell, England. It was designated a "new town" in 1949, when population relocation and growth required new housing stock, and was thus filled with mini-suburbs over subsequent decades.

Hence the claustrophic, artifical atmosphere.

Hence the claustrophic, artifical atmosphere.

Then to Platform 9 3/4, set in King's Cross, London.

Built in 1852, King's Cross is one the great Victorian architectural achievements, uniting engineering and architecture by using modern materials (metal girders and rolled glass) to create a functional yet beautiful station.

Built in 1852, King's Cross is one the great Victorian architectural achievements, uniting engineering and architecture by using modern materials (metal girders and rolled glass) to create a functional yet beautiful station.

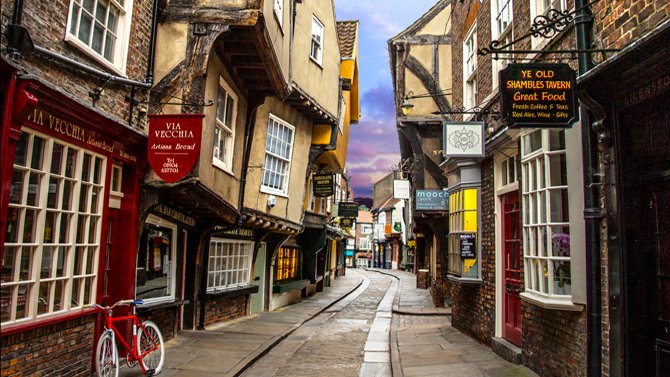

Diagon Alley resembles a street called the Shambles in York, England.

The narrowness of the street suggests it was laid out on a Medieval plan, with the buildings developing organically over the centuries.

This is charming urban vernacular (i.e. unplanned) at its best.

The narrowness of the street suggests it was laid out on a Medieval plan, with the buildings developing organically over the centuries.

This is charming urban vernacular (i.e. unplanned) at its best.

Unsurprisingly, Gringotts Bank stands apart from the Medieval charm with its imposing neoclassical design, pediments and porticos included.

It reminds us of London's 19th & early 20th century neoclassical buildings, like the Bank of England, which *look* like wealth and power.

It reminds us of London's 19th & early 20th century neoclassical buildings, like the Bank of England, which *look* like wealth and power.

The Burrow, home of the Weasleys, is the direct opposite of Privet Drive. A rural, smallholder's house, built by hand rather than the local council.

As often in cinema, when film-makers want to convey "homeliness" they turn to this sort of old-fashioned, vernacular rurality.

As often in cinema, when film-makers want to convey "homeliness" they turn to this sort of old-fashioned, vernacular rurality.

And while the Lovegood Household is ostensibly similar with that wonky appearance, its sleekness is more reminiscent of Antoni Gaudi's Catalan Modernisme or of "biomimetic" architecture.

Feels more like of a quirky architectural statement than a cosy, handmade hodge-podge.

Feels more like of a quirky architectural statement than a cosy, handmade hodge-podge.

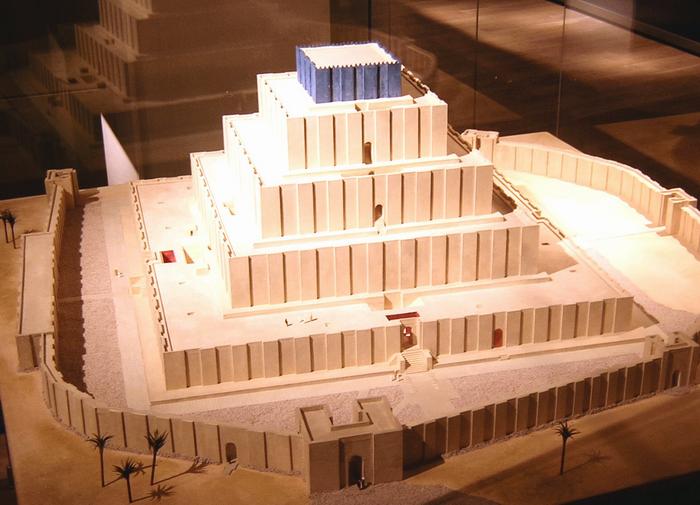

Azkaban pulls us in two directions. The simple geometric shape draws us to think of ancient architecture, like the Ziggurats of Mesopotamia.

Yet the height and abstractness, with a plain, glass-like surface, makes it feel more like a work of contemporary architecture.

Yet the height and abstractness, with a plain, glass-like surface, makes it feel more like a work of contemporary architecture.

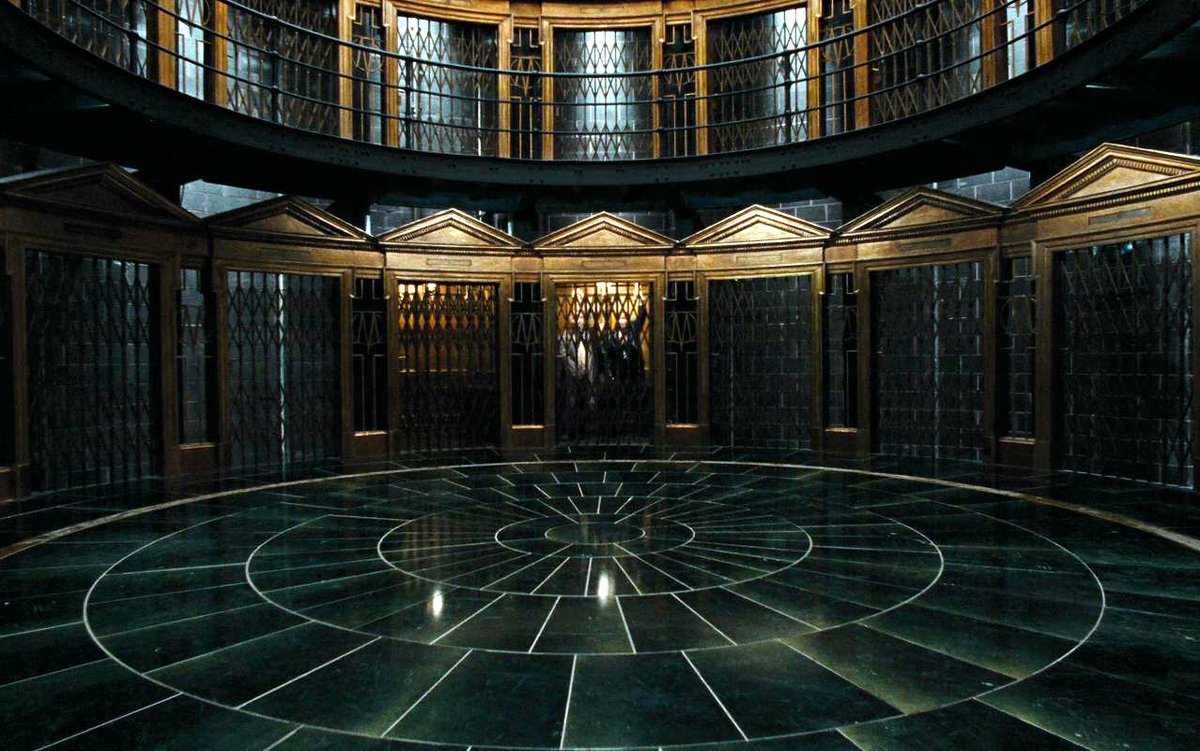

The Ministry of Magic's use of artfully crafted and lavish materials, such as bronze, gold, and marble, along with streamlined, modern forms and great size presents a vision of American (rather than English) Art Deco through and through.

Wealth, luxury, power, progress, might.

Wealth, luxury, power, progress, might.

The French Ministry of Magic, meanwhile, is simply the Grand Palais in Paris, a supreme statement of the Beaux-Arts style (and very French).

While America's version is actually set inside the neo-Gothic Woolworth Building, from 1913, less stereotypically American than Art Deco.

While America's version is actually set inside the neo-Gothic Woolworth Building, from 1913, less stereotypically American than Art Deco.

Hogsmeade, though set in Scotland, is a strikingly Germanic town.

Medieval German houses used those distinctively steep roofs, intended to prevent snow from building up and causing a collapse.

And, again, the Medieval vernacular creates a charming, friendly, authentic mood.

Medieval German houses used those distinctively steep roofs, intended to prevent snow from building up and causing a collapse.

And, again, the Medieval vernacular creates a charming, friendly, authentic mood.

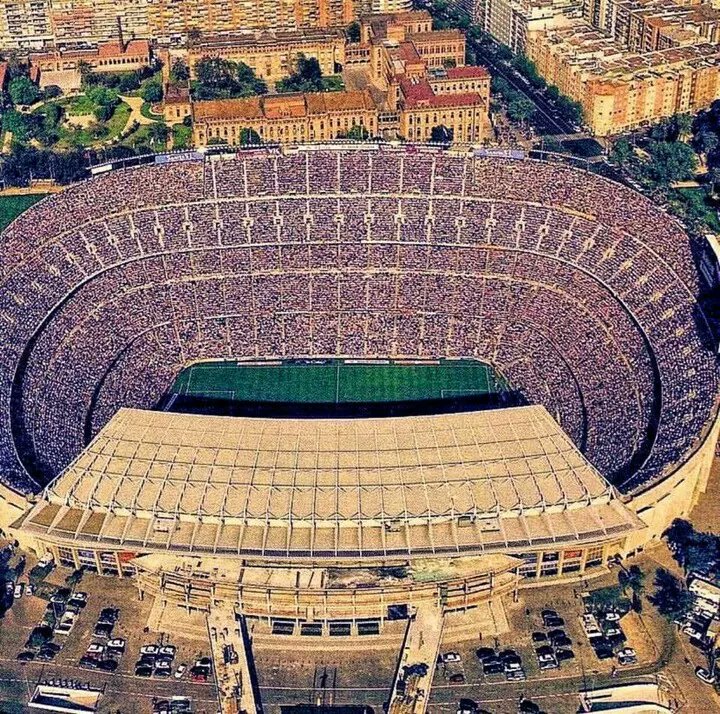

The Quidditch World Cup Stadium stands out as a startlingly modern megastructure.

Those huge, asymmetrial awnings remind us of Munich's Olympiastadion, completed in 1972, and the steep walls of spectators call to mind Barcelona's Camp Nou, a veritable cathedral of sport.

Those huge, asymmetrial awnings remind us of Munich's Olympiastadion, completed in 1972, and the steep walls of spectators call to mind Barcelona's Camp Nou, a veritable cathedral of sport.

Malfoy Manor was filmed at Hardwick Hall, a 16th century country house in England.

Elizabethan architecture was a relatively modest style, austere but not gloomy. Hence the addition of those dark spires to give a more imposing and menacing look, appropriate for the Malfoys.

Elizabethan architecture was a relatively modest style, austere but not gloomy. Hence the addition of those dark spires to give a more imposing and menacing look, appropriate for the Malfoys.

The Potter home in Godric's Hollow is vernacular, intended to be more "authentic" and "homely" than Privet Drive.

The vertical timbers infilled with plaster panels is known as "close-studding", a Medieval technique which was aesthetic rather than structural.

The vertical timbers infilled with plaster panels is known as "close-studding", a Medieval technique which was aesthetic rather than structural.

12 Grimauld Place was filmed in Claremont Square, London, a wonderful example of early 19th century Georgian architecture.

Its scaled-back neoclassicism is graceful rather than grand, with those subdued classical motifs conveying a certain elegance rather than ostentatiousness.

Its scaled-back neoclassicism is graceful rather than grand, with those subdued classical motifs conveying a certain elegance rather than ostentatiousness.

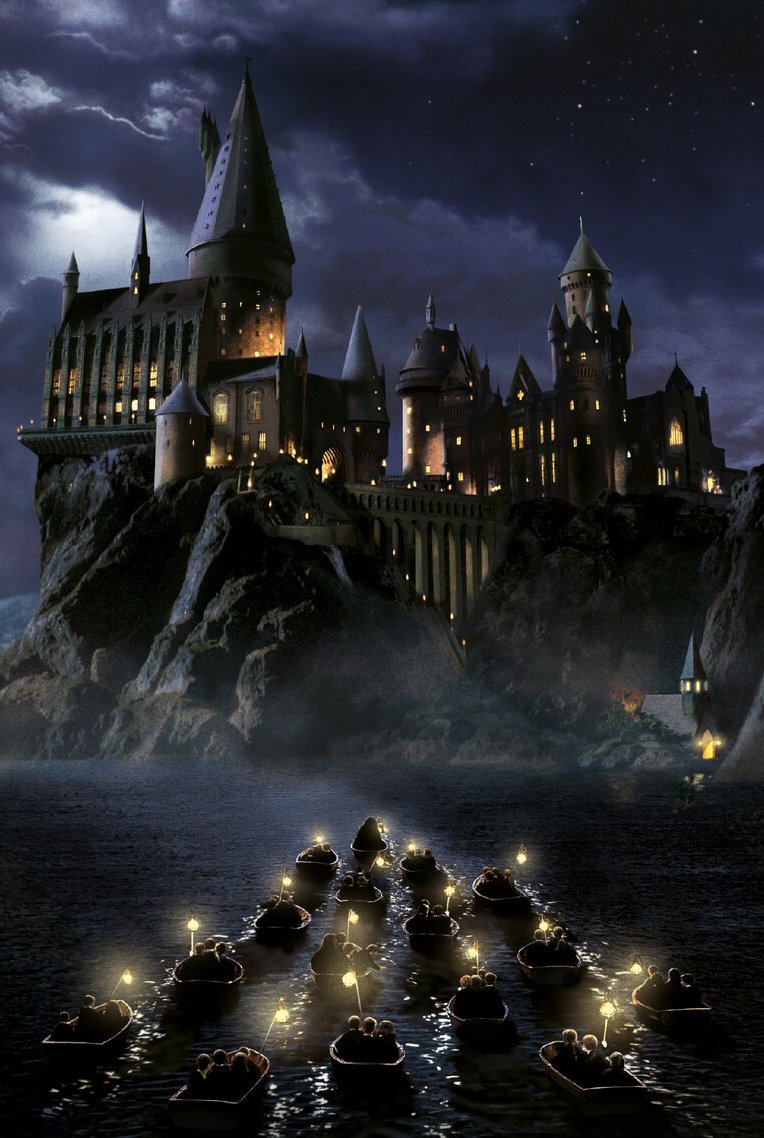

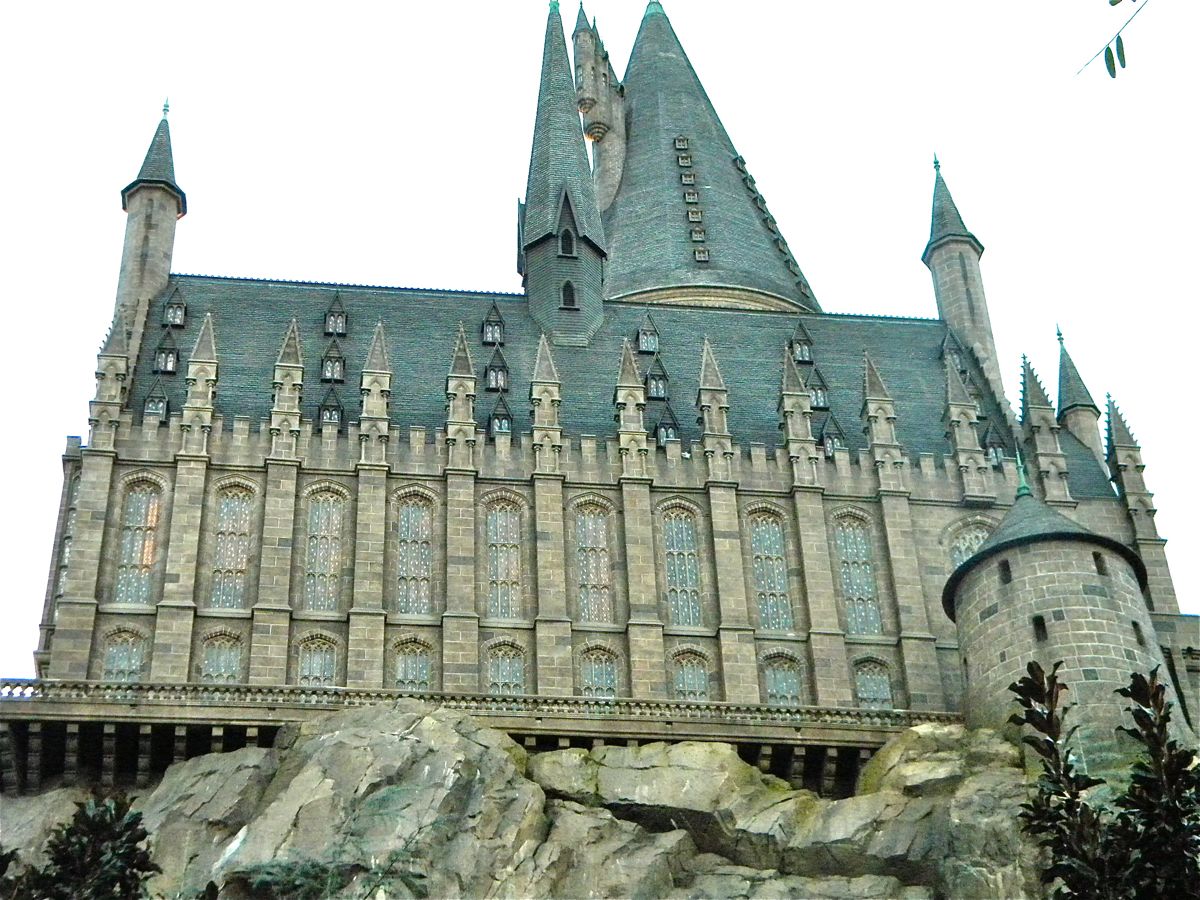

And now for Hogwarts itself, more of an ever-changing architectural matrix than a single place.

But there are some constant features even across its many incarnations. Two styles above all dominate Hogwarts, both the fictional castle itself and real filming locations.

But there are some constant features even across its many incarnations. Two styles above all dominate Hogwarts, both the fictional castle itself and real filming locations.

Hogwarts is a masterpiece of the "Scottish Baronial Style."

This neo-Gothic trend sprung up in the 19th century, when large manors in Scotland were built not as real but as fantasy castles, with distinctive circular towers and conical spires.

This neo-Gothic trend sprung up in the 19th century, when large manors in Scotland were built not as real but as fantasy castles, with distinctive circular towers and conical spires.

The designers of Hogwarts also make frequent use of "corbelled turrets". These are turrets which project *out* from another tower. They have a suitably eccentric appearance, especially when carried to unrealistic proportions, as they are in Hogwarts.

The rest of Hogwarts is largely compiled from (or filmed in) 13th-14th century Gothic buildings,

The "Early English" and "Decorative" Gothic styles from this era are still relatively simple, pretty but not ornate, charming but not overpowering.

The "Early English" and "Decorative" Gothic styles from this era are still relatively simple, pretty but not ornate, charming but not overpowering.

There's also a sprinkling of Norman architecture, which dominated until the arrival of the pointed arch in the 12th century.

Part of Hogwarts is modelled on Durham Cathedral, with its round arches, thick walls, and small windows, and also features as McGonigall's classroom.

Part of Hogwarts is modelled on Durham Cathedral, with its round arches, thick walls, and small windows, and also features as McGonigall's classroom.

It's intriguing that the film-makers largely stuck to Romanesque and early Gothic architectural styles, especially for Hogwarts' exterior.

From the 14th century onwards, Gothic architecture became increasingly elaborate, flamboyant, and orante. Would this have suited Hogwarts?

From the 14th century onwards, Gothic architecture became increasingly elaborate, flamboyant, and orante. Would this have suited Hogwarts?

Norman, Early Gothic, and Scots Baronial are all simpler and more robust than late Gothic architecture. They have a solid, older appearance.

The Great Hall reminds us of 1200s Salisbury Cathedral more than 1500s King's College Chapel, say, with its narrow windows.

The Great Hall reminds us of 1200s Salisbury Cathedral more than 1500s King's College Chapel, say, with its narrow windows.

That being said, Gloucester Cathedral, which provides some of the Hogwarts corridors, is an exemplar of late Gothic, "Perpendicular" style.

Notice the incredibly vibrant and flowing vaults on the corridor ceiling!

Notice the incredibly vibrant and flowing vaults on the corridor ceiling!

The power of architecture to shape our emotions and moods is nowhere more apparent than in cinema, where film-makers make very precise choices about how they want the audience to feel.

Why do the Weasleys and the Malfoys live in such different places? It's obvious, of course.

Why do the Weasleys and the Malfoys live in such different places? It's obvious, of course.

And yet the power of fictional buildings in films is *also* the power of buildings in real life.

They shape the atmosphere and the mood of a place, a home, or a city, they guide our emotions and impressions.

What can we learn from the fictional architecture of Harry Potter?

They shape the atmosphere and the mood of a place, a home, or a city, they guide our emotions and impressions.

What can we learn from the fictional architecture of Harry Potter?

Architecture is one of seven topics I write about in my free weekly newsletter, Areopagus.

If you'd like to join 45k+ other readers and make your week a little more interesting, useful, and beautiful, consider subscribing here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

If you'd like to join 45k+ other readers and make your week a little more interesting, useful, and beautiful, consider subscribing here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh