Exclamation Mark

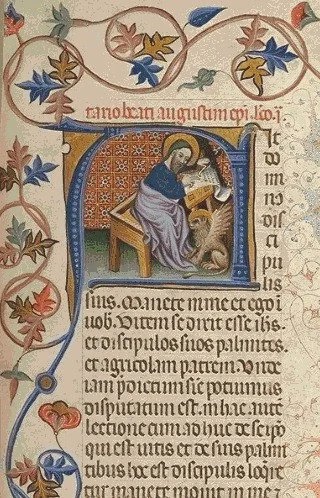

Possibly comes from the Latin phrase "io", which was an expression of joy. 14th century Medieval writers placed this at the end of sentences for emphasis. Eventually the I was placed above the O and it became an !

Got its current name in 1839.

Possibly comes from the Latin phrase "io", which was an expression of joy. 14th century Medieval writers placed this at the end of sentences for emphasis. Eventually the I was placed above the O and it became an !

Got its current name in 1839.

Question Mark

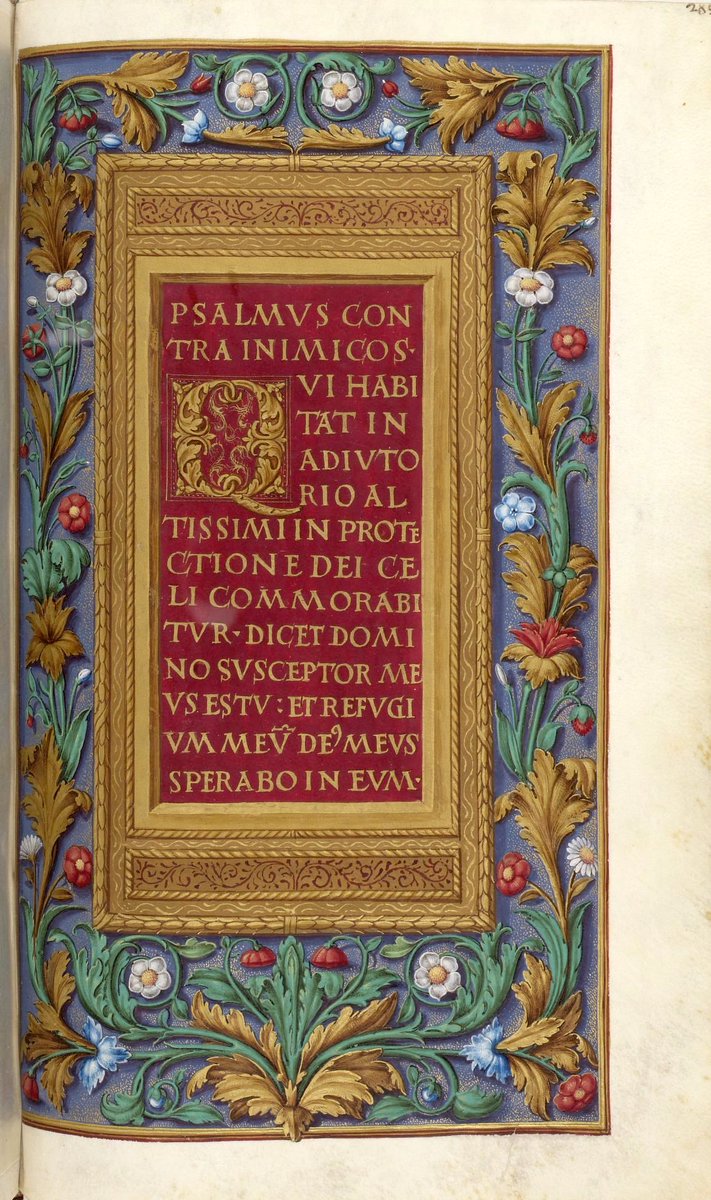

One of the oldest punctuation marks going: indicating a question in writing is important. Some theorise that it's actually an abbreviation for the Latin word "quaestio", but no evidence for this.

Has had many different forms over the centuries.

One of the oldest punctuation marks going: indicating a question in writing is important. Some theorise that it's actually an abbreviation for the Latin word "quaestio", but no evidence for this.

Has had many different forms over the centuries.

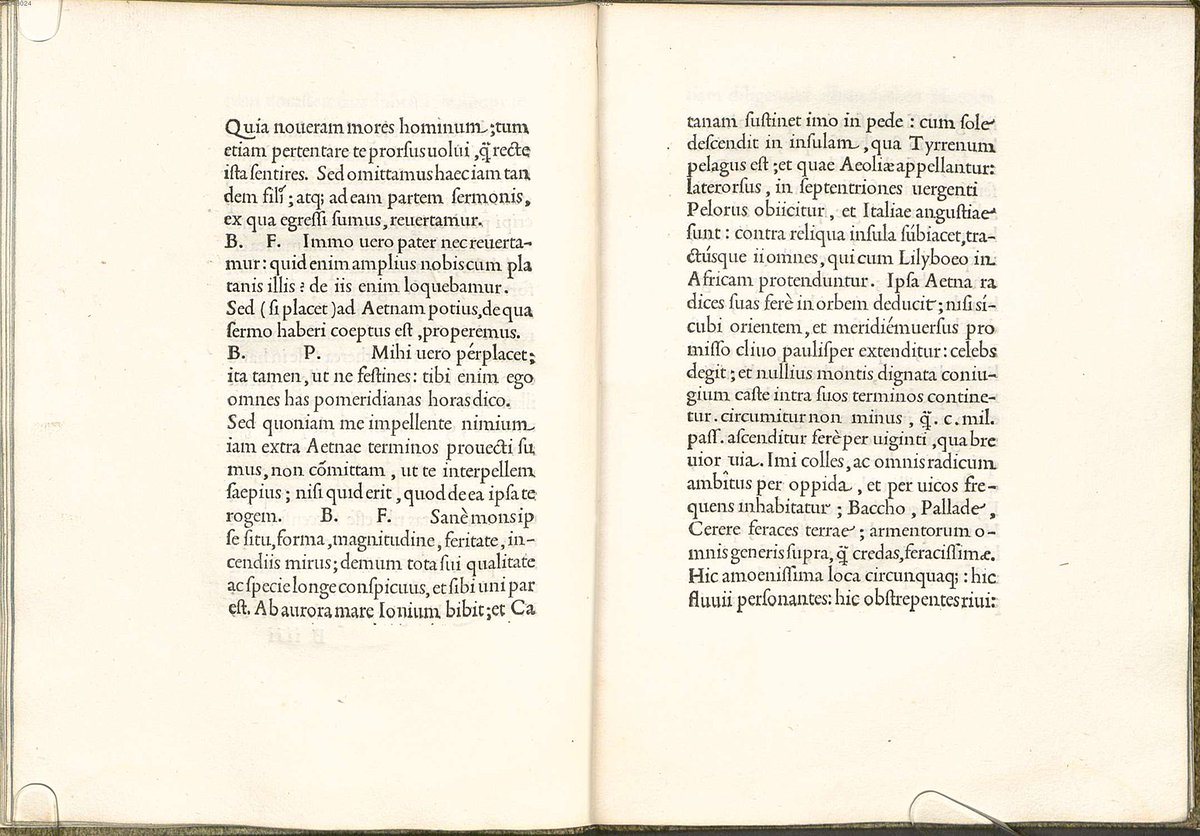

Full Stop

As with much punctuation, it originates in the work of an Alexandrian scholar called Aristophanes in the 3nd century BC.

He was chief librarian, and was sick of organising books which didn't even have spaces!

Had three forms at first. Simplified in the Middle Ages.

As with much punctuation, it originates in the work of an Alexandrian scholar called Aristophanes in the 3nd century BC.

He was chief librarian, and was sick of organising books which didn't even have spaces!

Had three forms at first. Simplified in the Middle Ages.

Colon

Also allegedly originated with Aristophanes as the single middot (·) until it was doubled up. The colon was long used to indicate a medium-length pause.

First properly attested in English in 1589, but its modern usage (e.g. for lists) is a more recent thing.

Also allegedly originated with Aristophanes as the single middot (·) until it was doubled up. The colon was long used to indicate a medium-length pause.

First properly attested in English in 1589, but its modern usage (e.g. for lists) is a more recent thing.

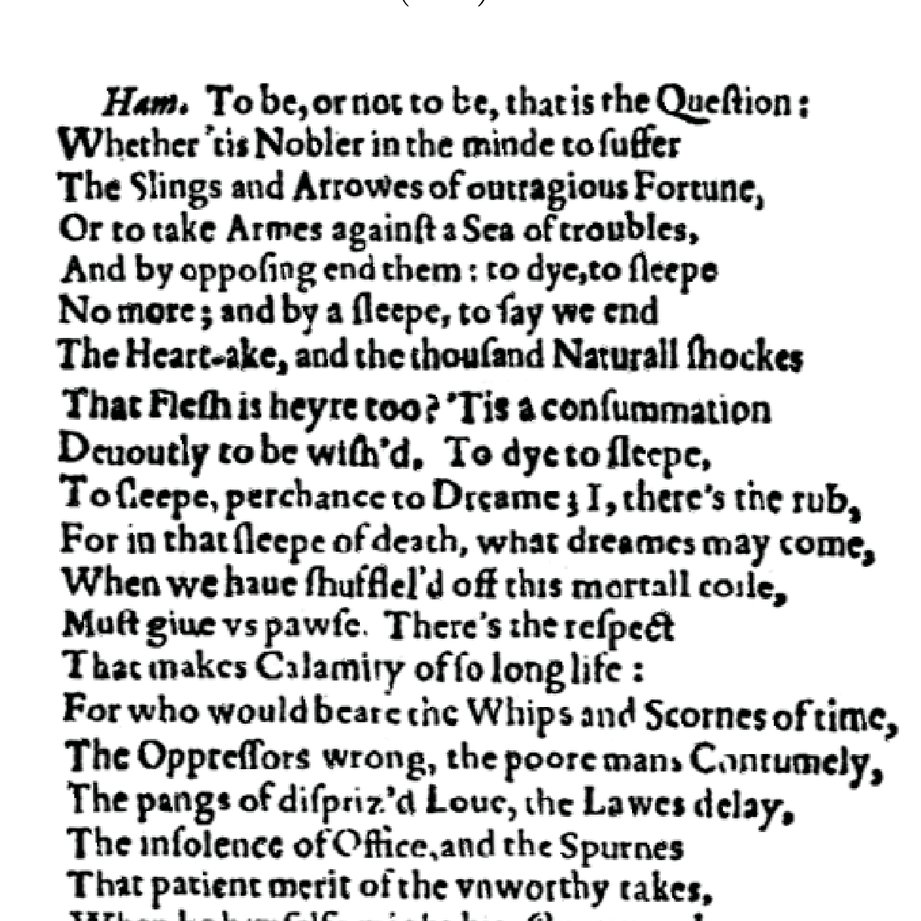

Semicolon

Has been used as an intermediary between the fullstop and colon/comma since the 16th century.

At first it was *another* form of pause length, but by the 18th century it had become (as now) a way of connecting two sentences related by meaning but not syntax.

Has been used as an intermediary between the fullstop and colon/comma since the 16th century.

At first it was *another* form of pause length, but by the 18th century it had become (as now) a way of connecting two sentences related by meaning but not syntax.

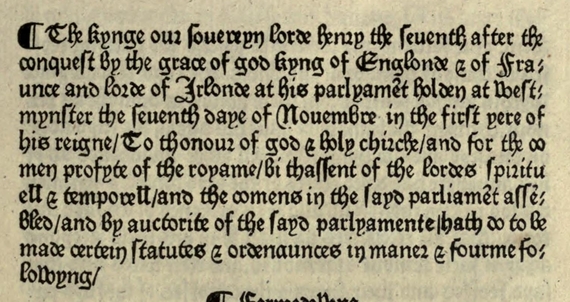

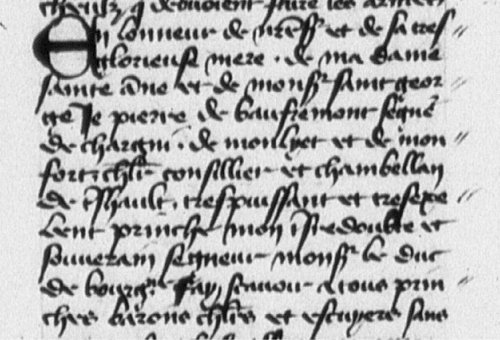

Comma

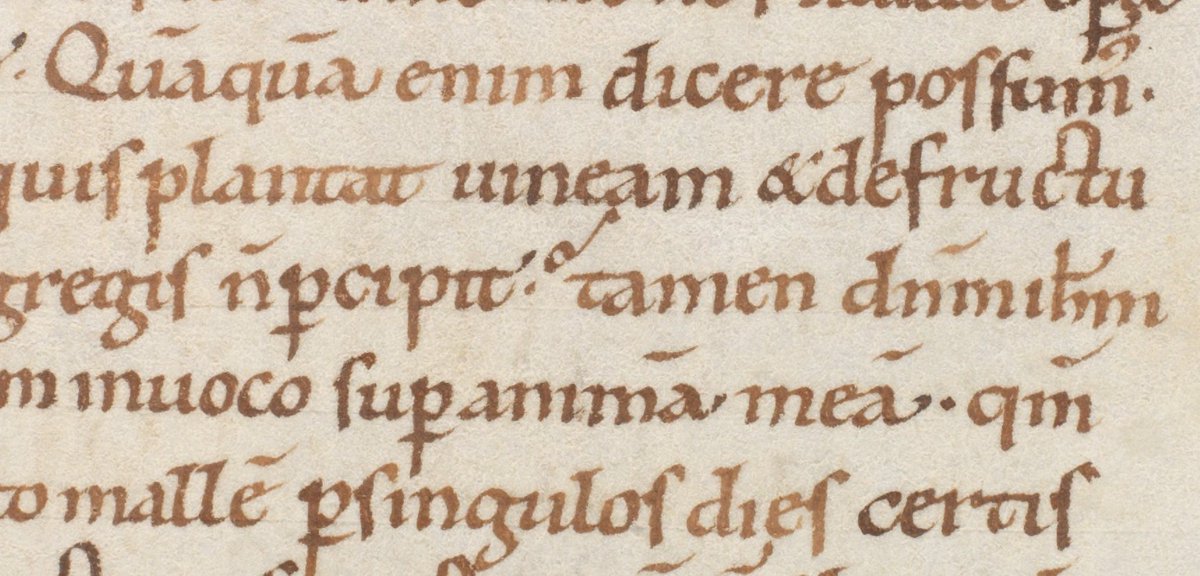

The *concept* of the comma as a pause in speech originates, like the colon, with Aristophanes' middot.

But the comma itself took the form of a slash (/) known as the virgula suspensiva during the Middle Ages.

That "/" was reshaped into the "," by the 17th century.

The *concept* of the comma as a pause in speech originates, like the colon, with Aristophanes' middot.

But the comma itself took the form of a slash (/) known as the virgula suspensiva during the Middle Ages.

That "/" was reshaped into the "," by the 17th century.

Parentheses

Their name refers to the Ancient Greek rhetorical concept - the inclusion of an supplementary information in the middle of a speech.

The rounded written form was termed "lunula" (i.e. moon-like) by Erasmus in the 16th century, but...

Their name refers to the Ancient Greek rhetorical concept - the inclusion of an supplementary information in the middle of a speech.

The rounded written form was termed "lunula" (i.e. moon-like) by Erasmus in the 16th century, but...

Chevron Brackets

...parentheses themselves are a little older than Erasmus; the chevron form had been used in the 13th century.

This, however, is as far back as the use of parentheses as a punctuation mark goes. And now chevron brackets have gone beyond their parenthetical use.

...parentheses themselves are a little older than Erasmus; the chevron form had been used in the 13th century.

This, however, is as far back as the use of parentheses as a punctuation mark goes. And now chevron brackets have gone beyond their parenthetical use.

Hyphen

Great history. First used like this ‿ by the grammarian Dionysius Thrax in 100 BC, before proper letter spacing, to indicate that two words should be read together.

So its purpose was the formation of compound words.

Great history. First used like this ‿ by the grammarian Dionysius Thrax in 100 BC, before proper letter spacing, to indicate that two words should be read together.

So its purpose was the formation of compound words.

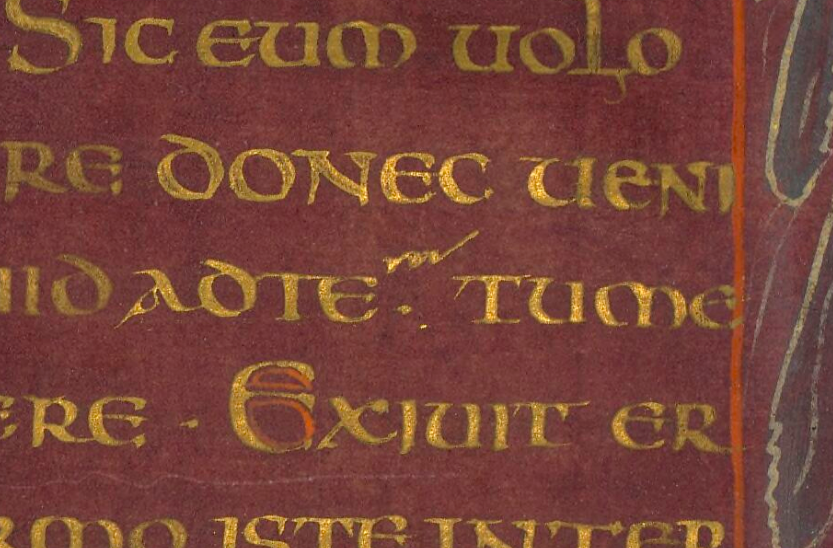

Then, during the Middle Ages, with the formal introduction of letter spacing, it was used to fix words in handwritten manuscripts that had been incorrectly spaced or spaced across two lines, kind of like a bandage. Was still written as ‿ or sometimes as an ⸗

When Gutenberg invented the printing press in the 15th century he couldn't put the ‿ because it was "sublinear" i.e. below the line of letters.

So he moved it to the middle of the line and the hyphen (-) as we know it today was born.

So he moved it to the middle of the line and the hyphen (-) as we know it today was born.

Dash

Regularly confused with the hyphen, but slightly longer (– versus -) and different origins.

Possibly originates in Italy in the 12th century as a sentence terminator, like a fullstop. By 18th century it had evolved into its flexible modern form and was in regular use.

Regularly confused with the hyphen, but slightly longer (– versus -) and different origins.

Possibly originates in Italy in the 12th century as a sentence terminator, like a fullstop. By 18th century it had evolved into its flexible modern form and was in regular use.

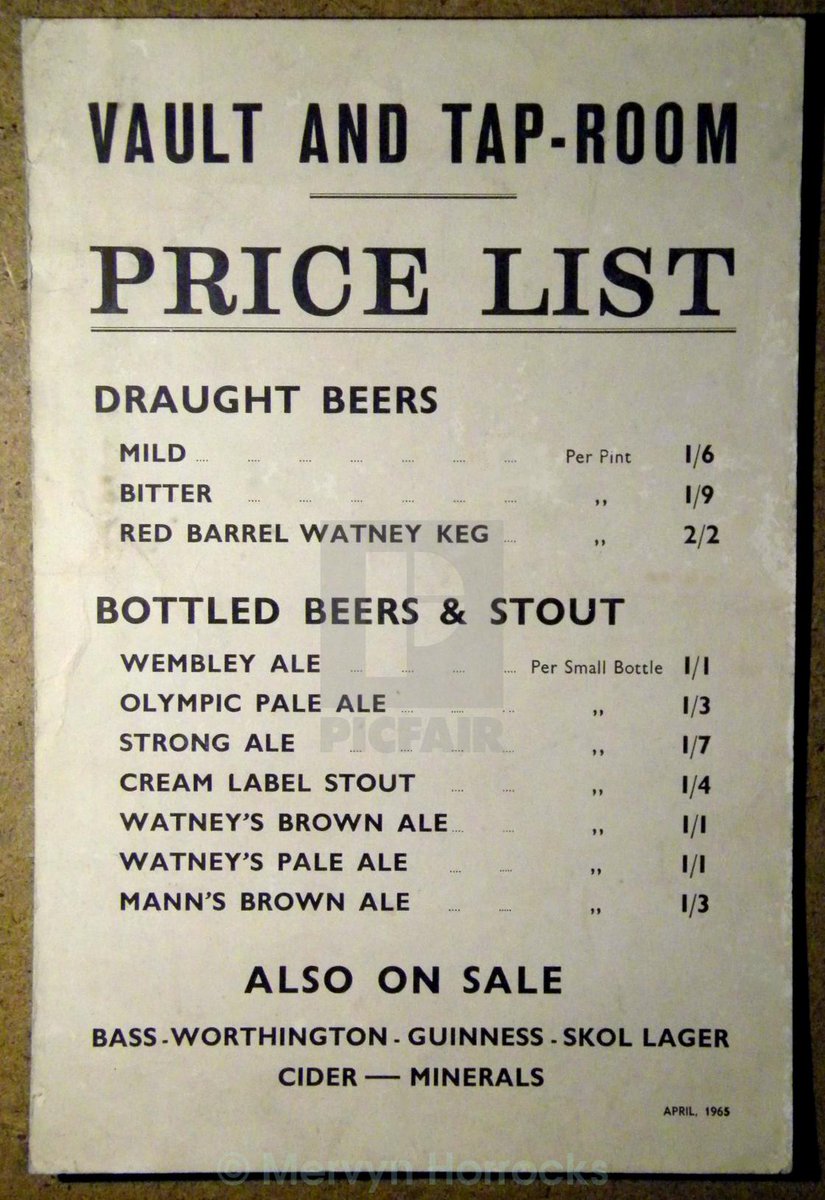

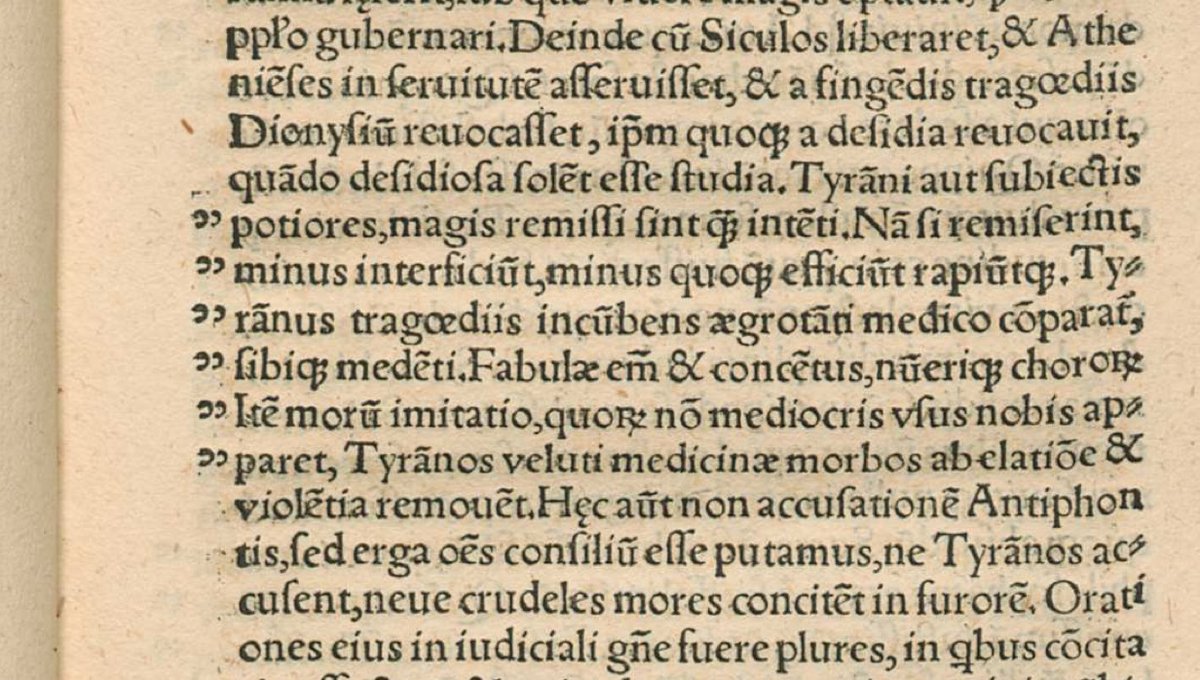

Slash

You will remember that the / symbol used to be a comma. Once replaced by , it became known as an oblique stroke, while the term "slash" is only from 1961.

Who could have known this Medieval mark would become so prevalent in computing?

Once the British shilling symbol.

You will remember that the / symbol used to be a comma. Once replaced by , it became known as an oblique stroke, while the term "slash" is only from 1961.

Who could have known this Medieval mark would become so prevalent in computing?

Once the British shilling symbol.

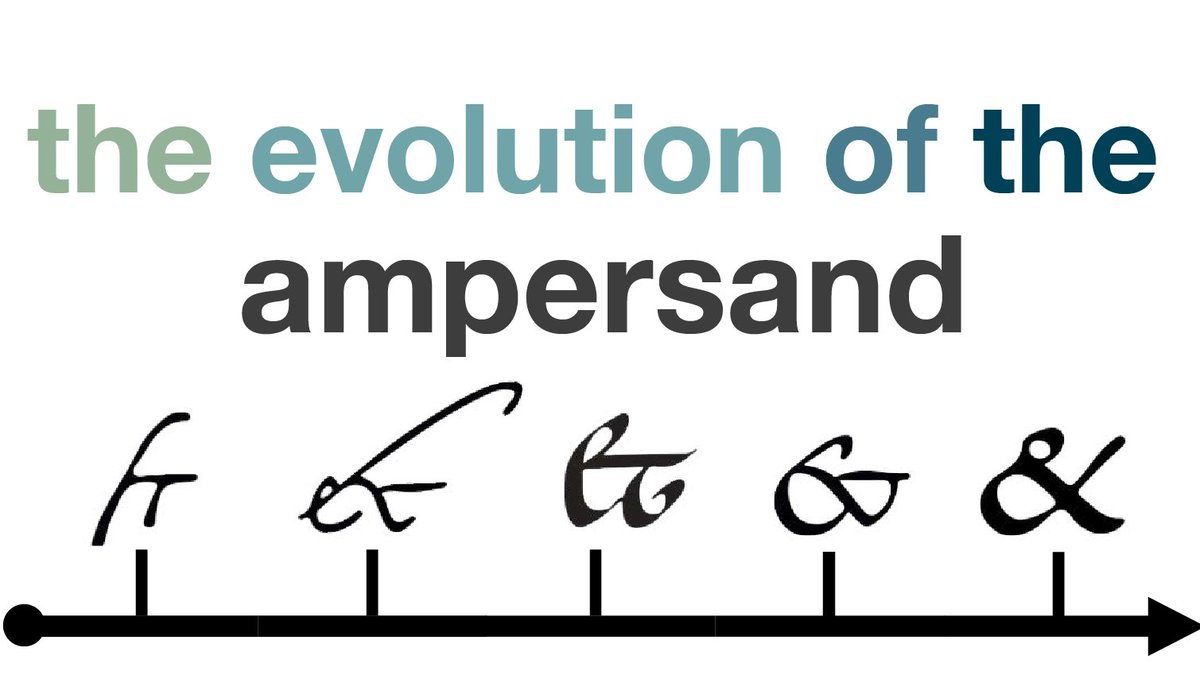

Ampersand

The symbol is a morph of the Latin word "et", meaning and. At least two thousand years old. Strong history.

The name comes from the fact that "&" was often added to the end of the alphabet, read aloud as "and per se &" which was squashed into "ampersand".

The symbol is a morph of the Latin word "et", meaning and. At least two thousand years old. Strong history.

The name comes from the fact that "&" was often added to the end of the alphabet, read aloud as "and per se &" which was squashed into "ampersand".

Asterisk

Aristarchus of Samothrace used them in the 2nd century BC when correcting mistakes in Homer, and Origen did the same thing in Alexandria in the 2nd century AD with his Hebrew texts. Consistent Medieval usage after that.

Perhaps the oldest unchanged punctuation mark.

Aristarchus of Samothrace used them in the 2nd century BC when correcting mistakes in Homer, and Origen did the same thing in Alexandria in the 2nd century AD with his Hebrew texts. Consistent Medieval usage after that.

Perhaps the oldest unchanged punctuation mark.

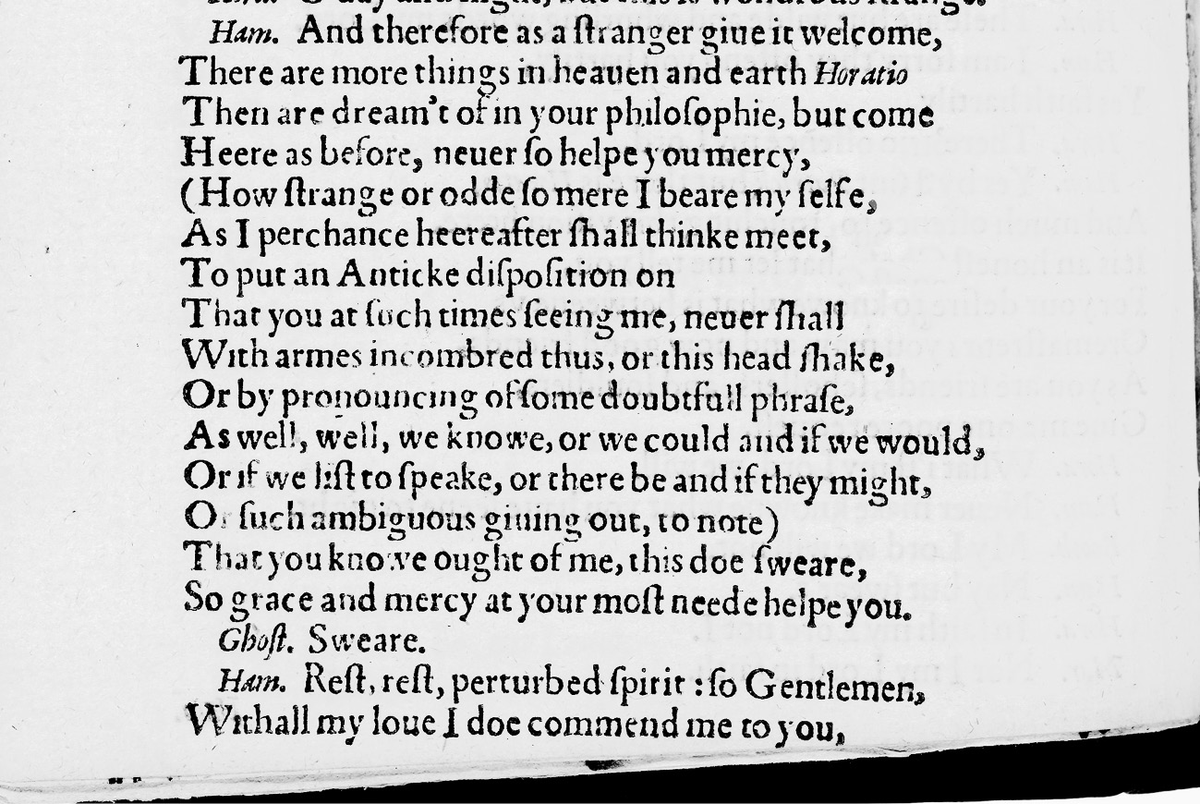

Apostrophe

15th century origins in Italy then imported to England as an elision marker (where a letter is removed, eg loved -> lov'd).

Hence possessive apostrophes. The possessive of King used to be Kinges. With an apostrophe it became King's. That then spread to all nouns.

15th century origins in Italy then imported to England as an elision marker (where a letter is removed, eg loved -> lov'd).

Hence possessive apostrophes. The possessive of King used to be Kinges. With an apostrophe it became King's. That then spread to all nouns.

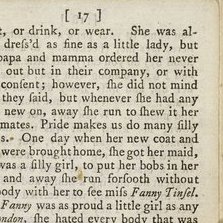

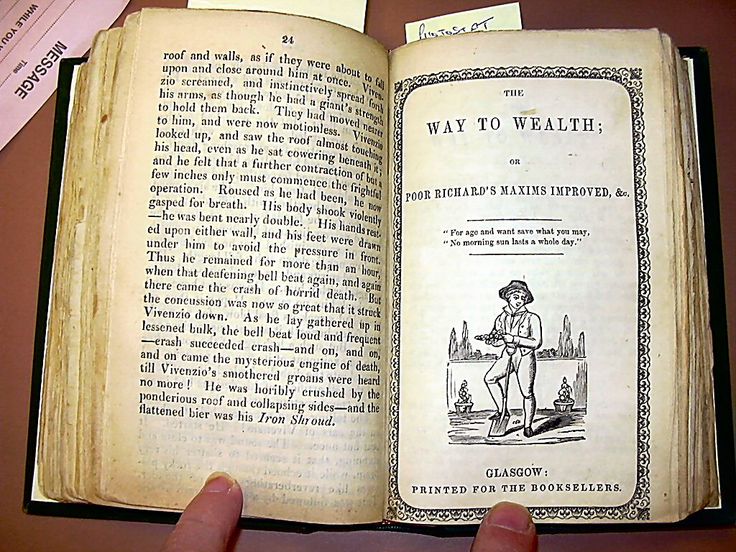

Quotation Marks

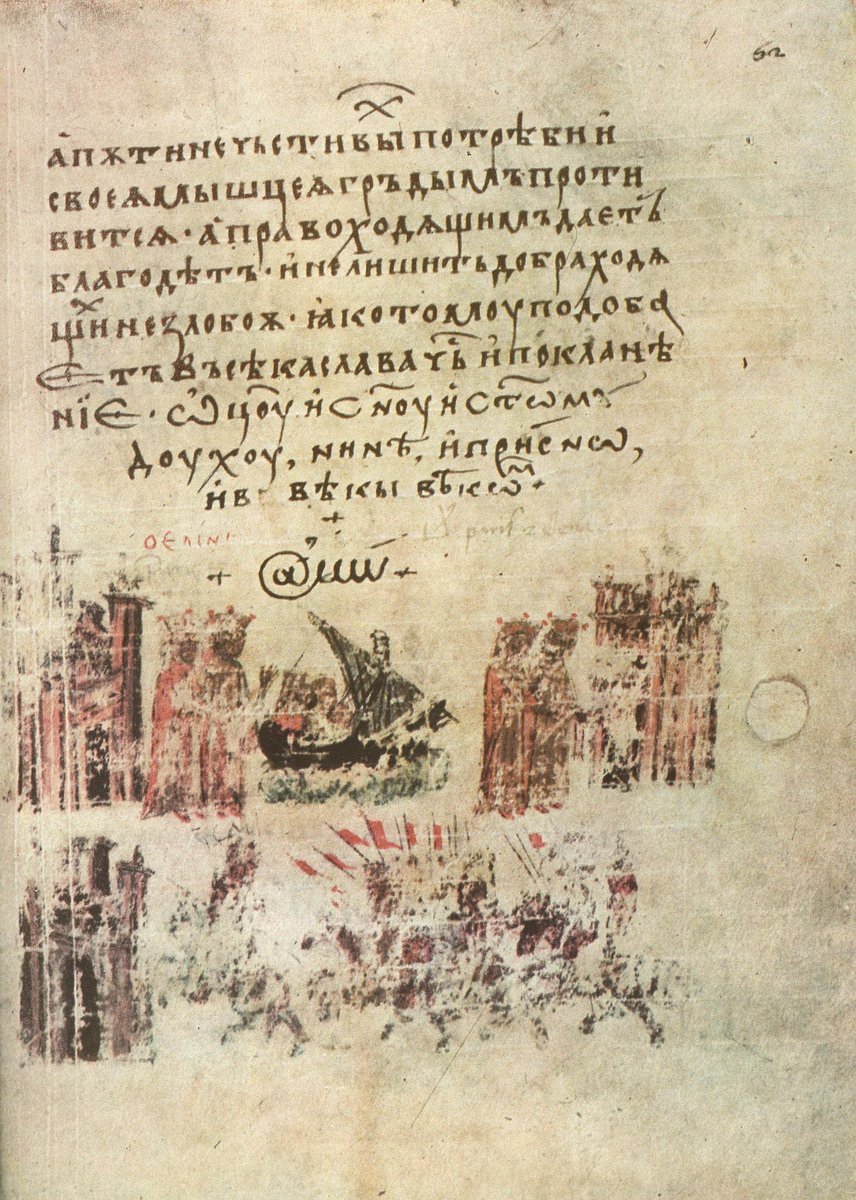

These started as notations in the margins of Medieval manuscripts either to indicate emphasis or to indicate that somebody else had said it.

By the 17th century in Britain these marks were being printed around the quote itself at the height of capitals.

These started as notations in the margins of Medieval manuscripts either to indicate emphasis or to indicate that somebody else had said it.

By the 17th century in Britain these marks were being printed around the quote itself at the height of capitals.

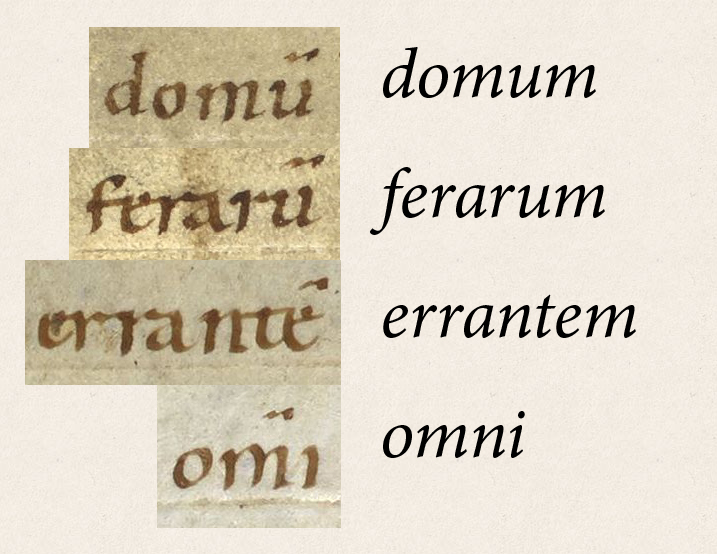

Tilde

The name itself has come into English from Latin via Portuguese.

An old mark used in the Middle Ages to indicate an abbreviation, especially in frequently used words (to save time and space).

Now has multiple uses in English, but not its original one.

The name itself has come into English from Latin via Portuguese.

An old mark used in the Middle Ages to indicate an abbreviation, especially in frequently used words (to save time and space).

Now has multiple uses in English, but not its original one.

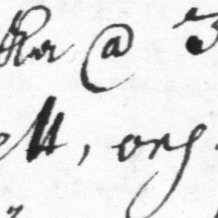

@

A surprisingly old symbol with various Medieval uses: in Bulgaria for the A in amen, as an abbreviation for arroba (a weight) in Spain, for amphora (a unit of volume) in Venice.

By the 17th century was being used as short for "at" in France.

A surprisingly old symbol with various Medieval uses: in Bulgaria for the A in amen, as an abbreviation for arroba (a weight) in Spain, for amphora (a unit of volume) in Venice.

By the 17th century was being used as short for "at" in France.

Hashtag

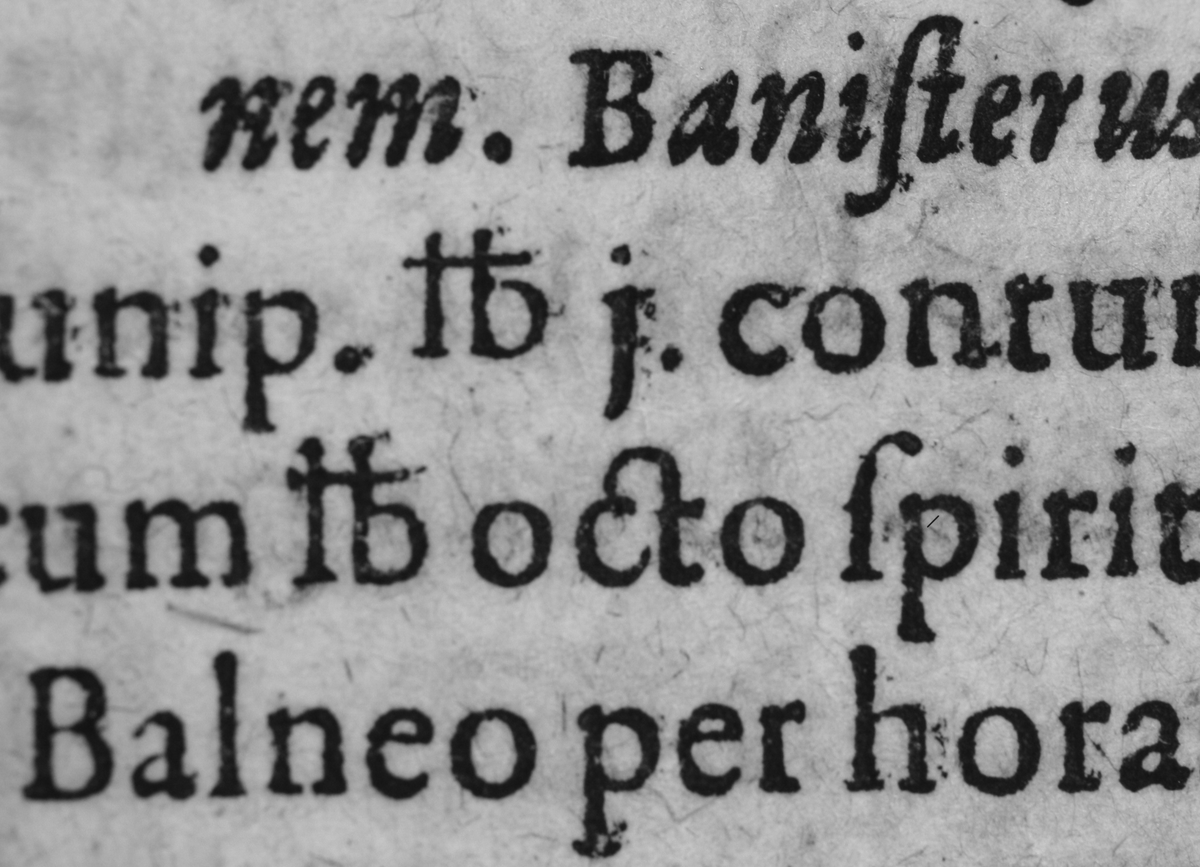

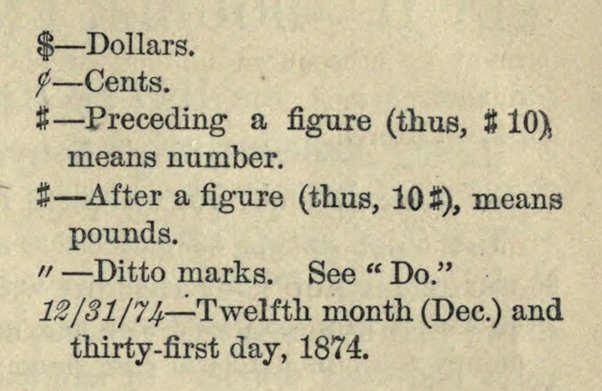

Originally morphed from the letters lb, an abbreviation for the Latin "libra pondo" which means "pound weight".

From a symbol for pound weight the hash then became a general number sign as early as the 1850s, perhaps because of its use in business accounts.

Originally morphed from the letters lb, an abbreviation for the Latin "libra pondo" which means "pound weight".

From a symbol for pound weight the hash then became a general number sign as early as the 1850s, perhaps because of its use in business accounts.

And that's a brief history of some of those scribbles, but there's a whole world of punctuation out there, literally.

Punctuation marks are used differently in other languages, and some languages have totally different marks altogether.

But that's a story for another day...

Punctuation marks are used differently in other languages, and some languages have totally different marks altogether.

But that's a story for another day...

What's remarkable is that these symbols were invented by frustrated librarians and scholarly monks scribbling in their books.

None of whom could have known that, hundreds or thousands of years later, we'd be using them on our smart phones every day, all over the world.

None of whom could have known that, hundreds or thousands of years later, we'd be using them on our smart phones every day, all over the world.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh