Ok so I am going to start the Neolithic explainer thread, and then at the end I will give some news.

So this is the popular conception of hunter gatherers. Running around in loincloths hunting wooly Mammooths. Fine, though a lot of hunting was actually small game trapping, and actually gathering of plants was a bigger source of calories (though proteins came mostly from hunts).

Hunting and gathering for food was almost universally paired with nomadism. That is the group would live in temporary camps, perhaps for a few days, perhaps for a few months, and then move to another location. This could be because they had exhausted the food available...

... or because the seasons had changed and food was now more abundant some place else. In some places like the Kalahari the issue is that water is available only at a few locations, and during the dry seasons eventually nomads deplete convenient food sources close to water.

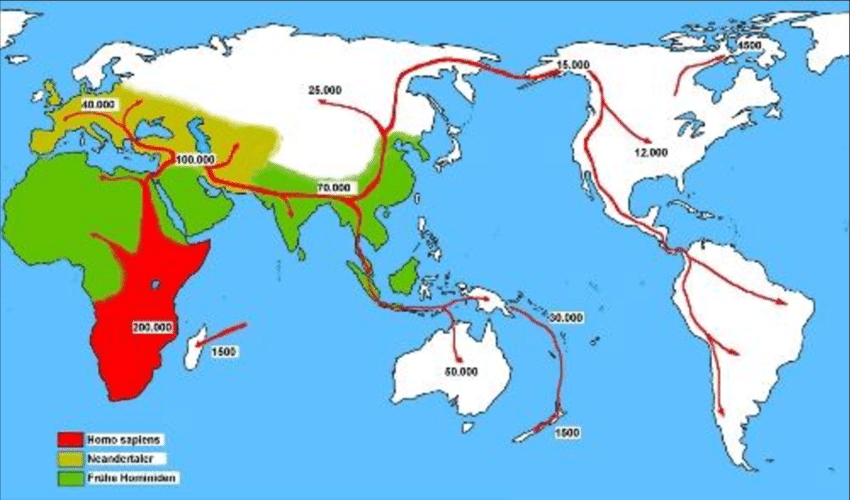

So anatomically modern humans appear about 200k years ago, and we leave Africa maybe 120k years ago, and we become behaviorally modern and are basically everywhere about 50k years ago, except the Americas that happened maybe 15-20k years ago (I think bit + but it's just a hunch)

So from the deserts to the arctic circle, humans are everywhere. You and I did this! You've got it in you to.

One thing to note is that we associate hunting and gathering and nomadism with harsh environments, but that's because farmers kicked HGs off any place they could farm.

One thing to note is that we associate hunting and gathering and nomadism with harsh environments, but that's because farmers kicked HGs off any place they could farm.

Back in the day, HGs lived in harsh place and mild places, resource poor places and gardens of Eden. Anywhere there was a blade of grass coming up through two rocks, humans either ate the grass, made it into rope, or ate the goat that ate the grass.

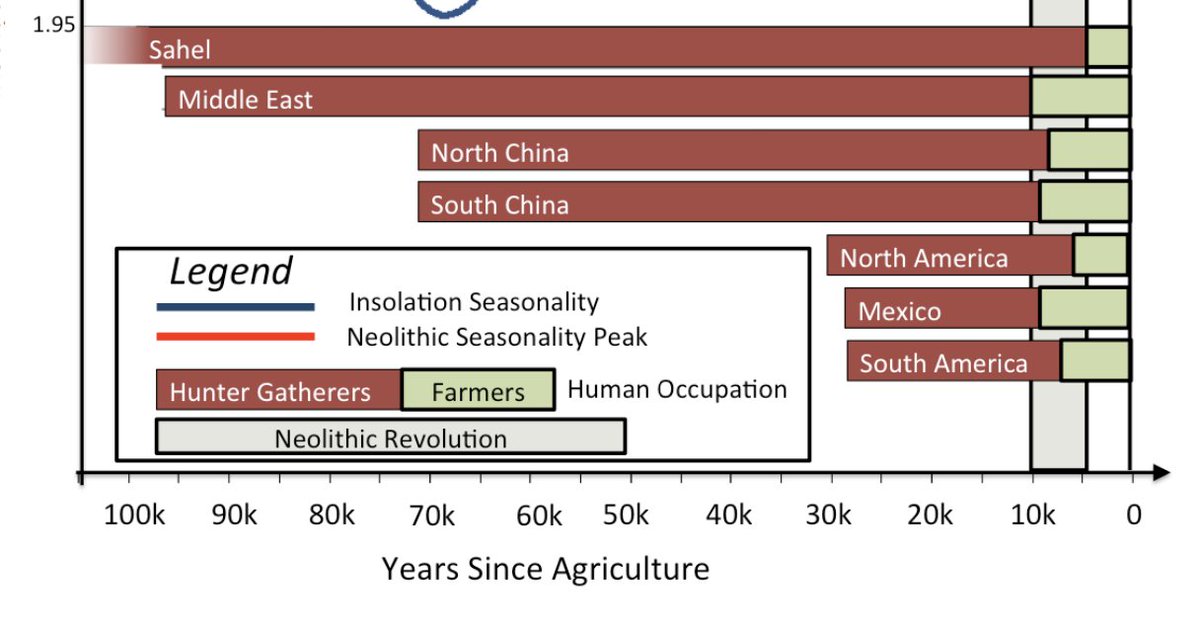

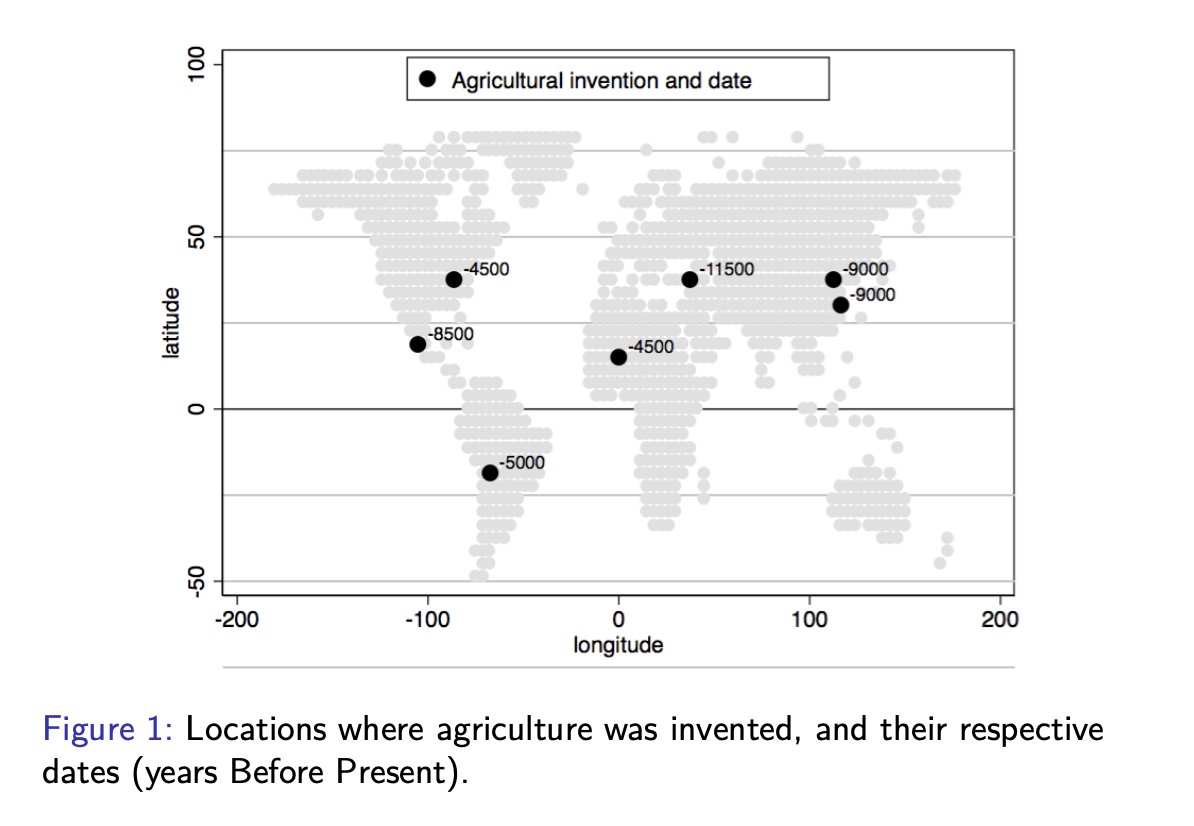

And then in a period of about 5-7k years, at least seven different locations adopted agriculture and became sedentary, all around the world, with seemingly no contact with each other!

So the first question is: what changed? Why did nobody seem to try agriculture for 150k years, and then all of a sudden people in North America and Sahel decide to give it a go basically at the same time (in archaeological terms?)

What was missing before, and became common later? And whatever it was, did the places that invented agriculture have more of whatever IT was?

And here's the bizarre part. The farmers actually got SHORTER, by a lot, when they started to farm. This was the same population that had hunting and gathering in the location for thousands of years. And they start farming, they get short, they have worse teeth, more joint wear.

And here's the other thing. Hunter gatherers are almost invariably nomadic, follow the herds around sort of thing. How do you invent farming, let alone get good at it, if you're never in the same place for more than a couple of months?

But why/how would you settle down, if you don't know how to farm? You rapidly exhaust natural foods and scare away the game.

Chicken and egg problem, really!

Chicken and egg problem, really!

So what we need is some X that

1) was absent everywhere while humans were exclusibely HGs

2) became common around 10k years ago.

3) was specifically present in the locations where agriculture was invented, at the times in which it was invented

1) was absent everywhere while humans were exclusibely HGs

2) became common around 10k years ago.

3) was specifically present in the locations where agriculture was invented, at the times in which it was invented

4) is compatible with farmers being shorter than their HG ancestors..

5) solves the chicken and egg problem.

Oh and lest we forget

6) is sufficiently broad and open-ended to allow for the endless variations in specific crop, cultivation techniques, institutions.

Tall order!

5) solves the chicken and egg problem.

Oh and lest we forget

6) is sufficiently broad and open-ended to allow for the endless variations in specific crop, cultivation techniques, institutions.

Tall order!

I think I have an answer that satisfies these six constraints, while being compatible with the major findings of the archaeological record.

Have to drive home now. Kids are sick. Post your favorite theories and I will discuss then when I log on.

The Megafauna Extinction (likely human caused) is part of it but it's kind of rare for predators to hunt their MAIN prey to extinction, because usually as prey gets scarce it kills off the predators.

https://twitter.com/karlbykarlsmith/status/1590064566725402624?s=20&t=qxiODe2TljvkqQ-eBiOBhQ

You end up with the Lotke-Volterra thing instead. Predators can make a species extinct if they are eating something else most of the time, and there's this juicy mastodon whenever we want a quick snack.

E.g. the Angoamerican hunters that exterminated the bison ate crops most of the time!It's also unclear why people in N America and the Sahel should run out of pachiderms at the same time and decide to farm, rather than the more traditional response to famine, die in large numbers

https://twitter.com/GregWert/status/1590069817570394112?s=20&t=-0tvtZd2F3Dw6VwkZyt3bgSome forms of limited horticulture were indeed practiced by nomads, but these were usually luxury crops (e.g. tobacco), not the main source of sustenance. You can't abandon your main source of food to animals or competing groups!

https://twitter.com/Lord_Snoooty/status/1590065648260218880?s=20&t=-0tvtZd2F3Dw6VwkZyt3bgAbsolutely, though note that following herds around is exhausting, and more specifically it makes it impossible to develop heavy tech like kilns or smelters. So it's farming in a sense, but not in the sense that leads to this.

But this leads to an important point. Why was agriculture important? Why wouldn't a more efficient trap or a better fishing net be as important? Main thing: you can bring domesticated crops with you and create a close replica of your society in another place.

The other important point is that domesticating crops involved solving some deep existential issue for the plant. E.g. wild oats have to find a crack to fall into to avoid predation by ants. Humans solve this by planting the seed.

The first important point here is that the humans can now plant one seed and eat the other seven or whatever, which would otherwise have gone to the ants, but the second is that the plant will naturally evolve to lose the "walking attributes" and the energy can go into making...

... more and better seed. It is this coevolution of farmer and crop that makes agriculture such a powerful economic growth engine.

This is absolutely true. The last Ice Age ended about 11,000 years ago and weather in the Northern Hemisphere got quite a bit warmer. But on further investigation it doesn't pan out.

https://twitter.com/MatthewDownhour/status/1590078044144021504?s=20&t=-0tvtZd2F3Dw6VwkZyt3bg

The weather did get warmer, but most of the effect was that really cold place got not quite as cold but still pretty cold. If you wanted average conditions like those seen in the places that invented agriculture, you could have gotten them during the ice age: just go a bit south!

The places that invented agriculture were neither consistently warm nor rainy, but rather they spanned the gamut from the Sahel to Eastern North America, which are about as different conditions as you will find dense human populations in.

Second pause gotta put the kids down for nap.

Ok so now, my answer! Believe it or not, it is down to extrateresstrial forces.

No not aliens, the gravitational attraction of Jupiter. But let's take a step back.

No not aliens, the gravitational attraction of Jupiter. But let's take a step back.

Recall that a big reason why agriculture is difficult to develop past rudimentary horticulture is that nomadic hunter gatherers are well, nomadic, and they're always moving around. Hard to farm if you don't live with your crops!

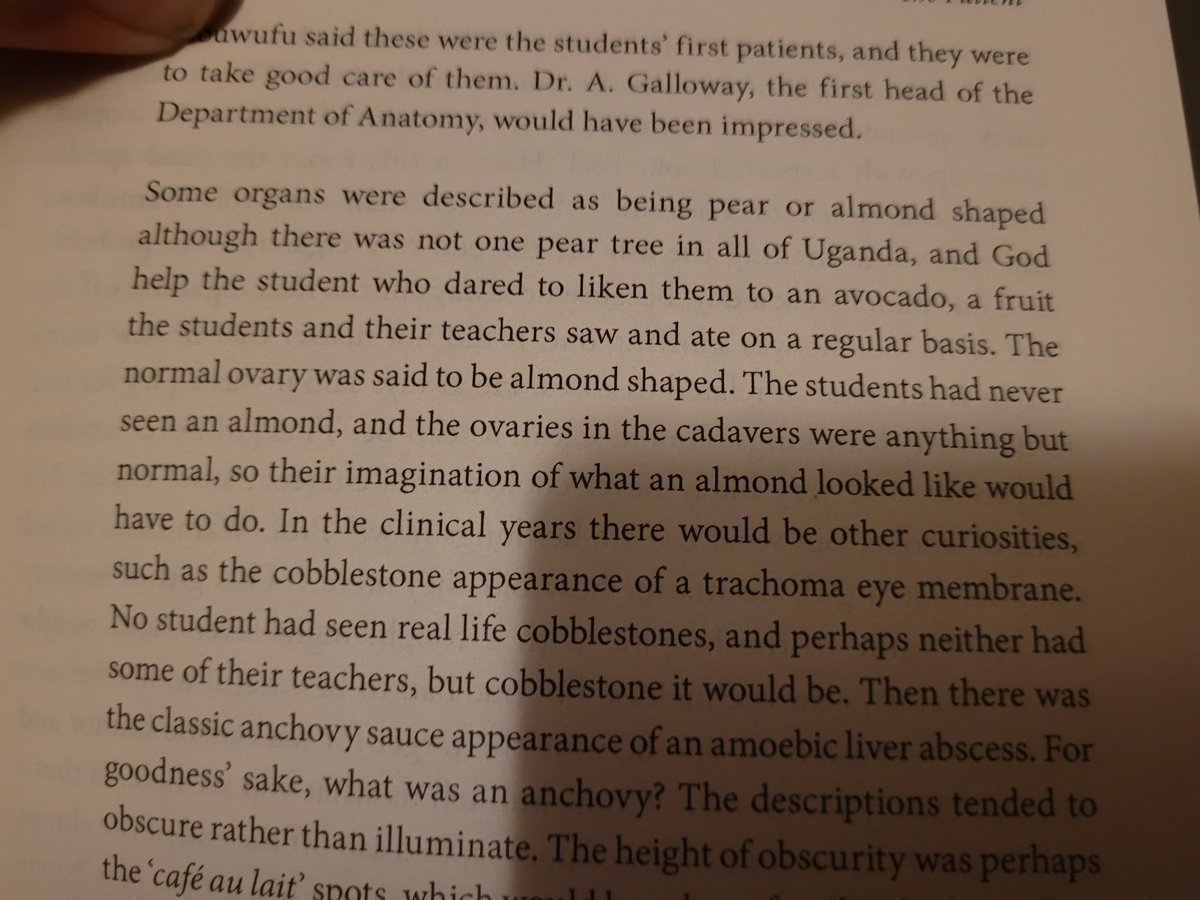

It's not that they don't understand the biology. E.g. recently contacted HGs invariably knew that seeds in the ground result in new plants, but you know that too, but that doesn't make you a farmer. Farming is a sum of a few big things and a thousand of little details.

You're just not going to figure out what's going wrong if you plant a crop, come back in six months, and find it eaten or dead. What was the weather like? Where there insects eating the leaves?

But on the other hand herds move around, and snowy peaks become lush pastures just as the warm plains become parched, so if there's no crops to guard, why not move with the abundance? This is the chicken and egg problem from before.

So here's what I will do. First I am going to propose a reason why hunter gatherers would become sedentary without knowing about agriculture.

Then I will show that this reason can also explain other things we know about the Neolithic.

...

Then I will show that this reason can also explain other things we know about the Neolithic.

...

...

Finally, I will show that this reason predicts both the general locations where agriculture was invented, the speed at which their neighbors adopted, and also a few other things along the way.

Finally, I will show that this reason predicts both the general locations where agriculture was invented, the speed at which their neighbors adopted, and also a few other things along the way.

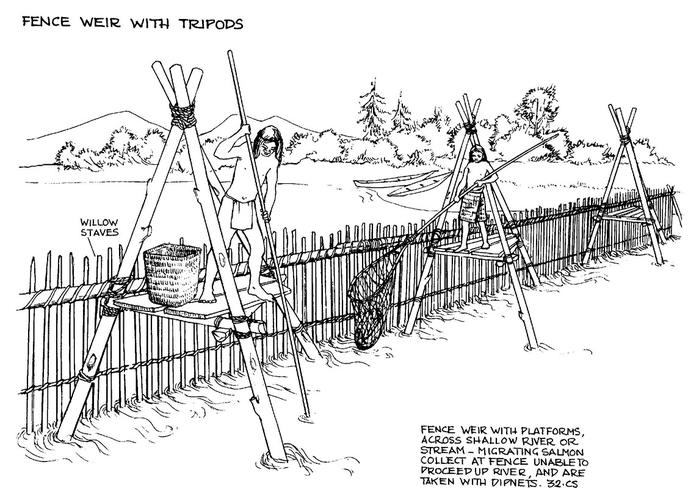

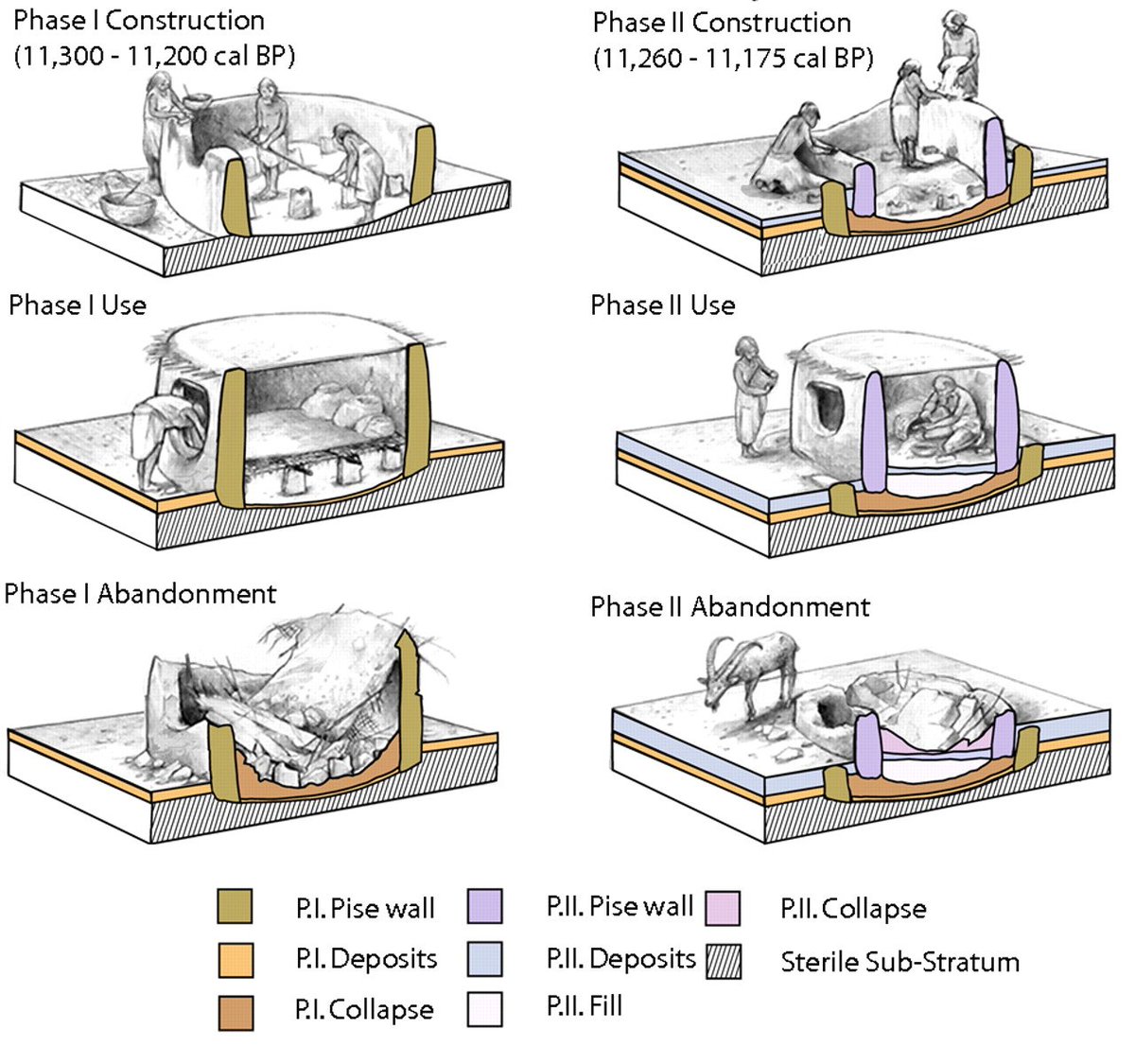

So why become sedentary if you don't know how to farm? This is the paper that gave me the key insight by Testart. He pointed out that there's quite a few cases of hunter gatherers that have become sedentary in order to store food. alaintestart.com/UK/documents/s…

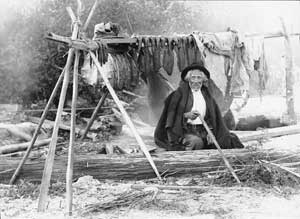

And when they were sedentary, hunter gatherers generally developed many of the trappings we associate with settled farmers, complex multilevel social hierarchies, gift cultures, accumulation of goods. A farming village without the farming.

For this to happen two things have to be true. Food has to be seasonally abundant, but also very scarce for extended parts of the year, and one of these seasonally abundant foods has to be storable, either as is or after processing. Like a good case, motive and opportunity.

For example in the Pacific Northwest, Native Americans harvested the seasonal salmon run, smoked them, and survived the winter by living off of their stores. They developed elaborate material cultures, stratified societies, permanent settlement. Farming villages without farming.

Now in the case of PNW Native Americans, this could not lead to agriculture for the simple reason that the salmon lifecycle involves a stage at sea. Without control over the stored species, domestication is basically impossible.

They couldn't take some salmon roe with them in a pouch, move to Iowa and start a copy of their society over there. It's an astoundingly successful feat of hunting and gathering, it doesn't replicate. It's not a franchiseable model. Agriculture is the McDonalds of lifestyles.

But what if for some reason, a lot of different nomadic hunter gatherers suddenly had a reason to store food? In many cases there might be no suitably abundant storable species. But where there was, it would be very reasonable to become sedentary in order to store this food.

And if this species that they were intensively storing happened to be a bit more susceptible to cultivation than salmon, well that would just be grand.

Given that they were already sedentary and living off of stored food for most of the year, investing in a little bit of effort into protecting, and later improving on the wild harvest would be obvious and easy. A fence to keep out herbivores. A drainage ditch to prevent flooding.

Not technically farming per se in a strict sense, but already effort expended to improve on the natural availability of food. Farming enough for this economist! And from settled, storing land stewards to farmers there is some road to travel, but each step is small.

So if you provide a reason why a lot of nomadic hunter gatherers become settled storers, you are 90% of the way to explaining the Neolithic Revolution as a global phenomenon.

Since there is no reason to believe that storage would became suddenly easier worldwide*, we are left with a sudden global increase in seasonality, which would make nomadism ineffective and storage necessary.

*ok, one potential reason, better understanding of astronomy

*ok, one potential reason, better understanding of astronomy

And indeed such an increase in seasonality did happen. It's related to the end of the Ice Age, but not how you (probably) think.

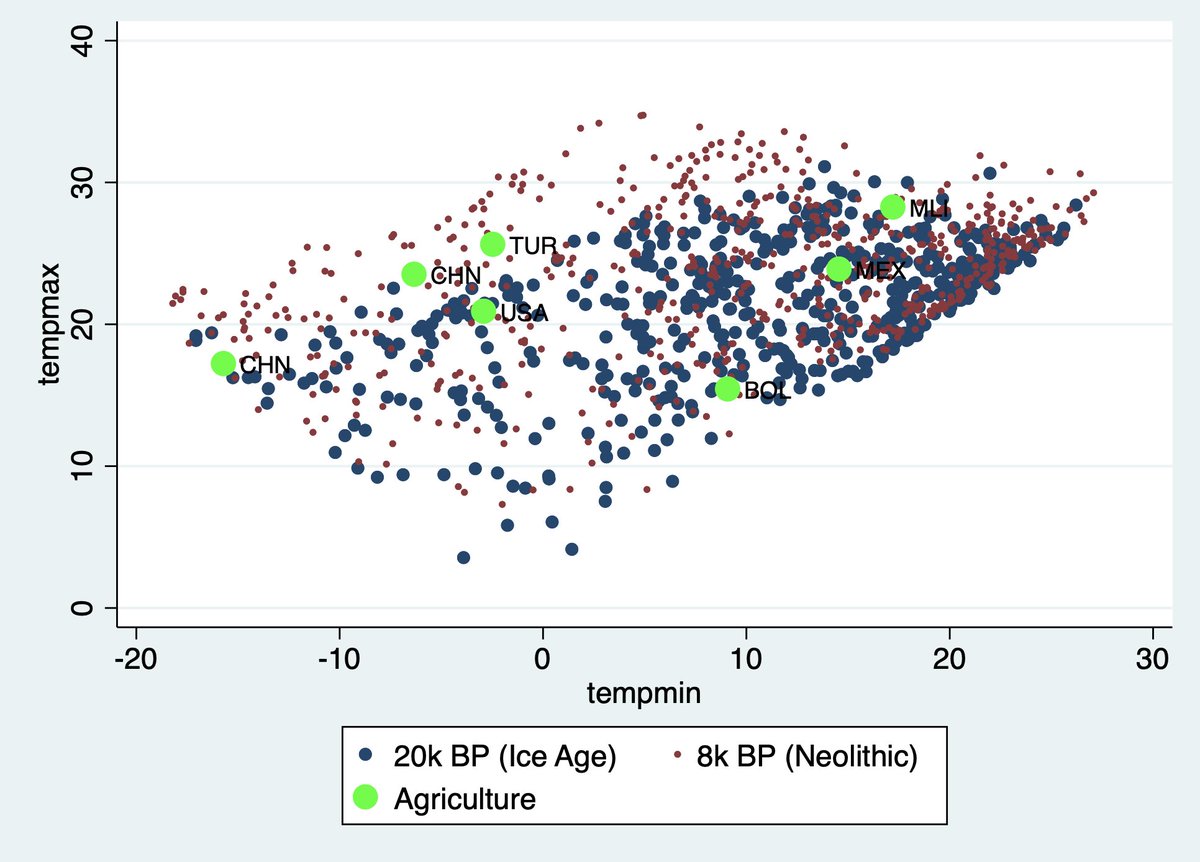

Look at this plot for temperature minimum and maximum, for 20k years ago (Ice Age) and 10k years ago. See that area in the upper left where there's red dot but no blue dots? Those are places with winters well below freezing, but summers above 20 degrees C.

These places were rare during the ice age, and common thereafter, and North and South China, Turkey and North America had this climate during the Neolithic, but not before.

esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1890/07… Such climates are called no-analog communities, combinations of species that don't exist during other periods (during the ice age, or today) because the environmental conditions do not exist today.

Why are those places so seasonal? Well look at them. They are all on the same rough latitude band of 30 to 40 degrees. Any more to the north, and the summers wouldn't be as abundant. Any more to the South and the winters wouldn't be as harsh.

Not only that but they are in the northern hemisphere (more on this later), the one with all the landmass. And where are they in this landmass? Away from the western coasts of continents, which have milder weather because prevailing winds bring ocean air.

What about those other three locations that are on the Equator? Well they're not ON the Equator, they are CLOSE to the equator. And therefore they suffer from very seasonal precipitation, as the intertropical convergence zone and its rains periodically visits them, and retreats.

here is a gorgeous animation of Net Primary Productivity (photosynthesis - respiration) by plants over the course of a few years. Watch it full screen because it's fantastic.

In fact if you just look at the ebb and flow of photosynthesis, you can let your eyes defocus and just let yourself be rocked by the breathing of our Mother Earth, and you will find yourself taken by a state of deep relaxation making you more and more convinced of my theory.

So agriculture was invented in a bunch of super seasonal places, some had high temperature seasonality, some had high precipitation seasonality, some had high temperature seasonality, and some had both. But what changed 11k years ago to make them all start at the same-ish time?

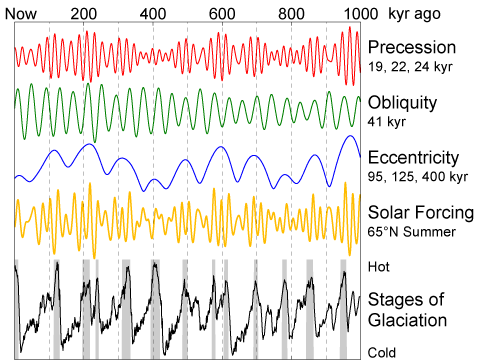

The answer is Milankovitch cycles, named after Serbian Geophysicists Milutin Milankovitch, which actually worked out the theory in a WWI prison camp!

The seasons of Earth depend mainly on three parameters. The most important is obliquity of the cycle, but eccentricity (how elliptical the orbit is), and the procession of the equinoxes (which hemisphere is pointed towards the Sun when we're closest).

All of these parameters CHANGE over time, due mostly to the orbital pull from Jupiter (I PROMISED EXTRATERRESTRIAL FORCES). Also the cycles have different lengths. And guess when they all synched up to deliver extra strong seasonality? That's right, just before the Neolithic!

Ok evening daddy stuff time. Rest of the thread and the news tonight.

https://twitter.com/andreamatranga/status/1590148532002250752?t=W_jfihHTjunwG0VqC4cUzA&s=19sorry broke the thread. Continues here

Ok. Let's finish this. So 12k years ago, we had a rare convergence in the Precession, Obliquity, and Eccentricity cycles, creating the most seasonal conditions of the last hundred thousand years or so.

What happened next?

What happened next?

Milankovitch showed that when Northern Hemisphere insolation seasonality is high, it ends Ice Ages, because warm summers lead to more glacier melt, while cold winters deposit less snow. This started happening 15k years ago, but was interrupted by the colder Younger Dryas event.

Increasing temperatures were important to agriculture because they made for very favorable conditions in winter in the temperate hemisphere, while keeping the winters miserable. During the Ice Age, the tropics were just as favorable, but didn't have the harsh winters.

And of course this effect was magnified by the fact that seasonality itself was higher than at any point since humans had acquired behavioral modernity.

Closer to the tropics a similar effect seems to have been going on with a strengthened monsoon, though past precipitation levels are harder to reconstruct globally than temperatures.

The two types of seasonality pushed HG groups to become sedentary so as to be able to store.

The two types of seasonality pushed HG groups to become sedentary so as to be able to store.

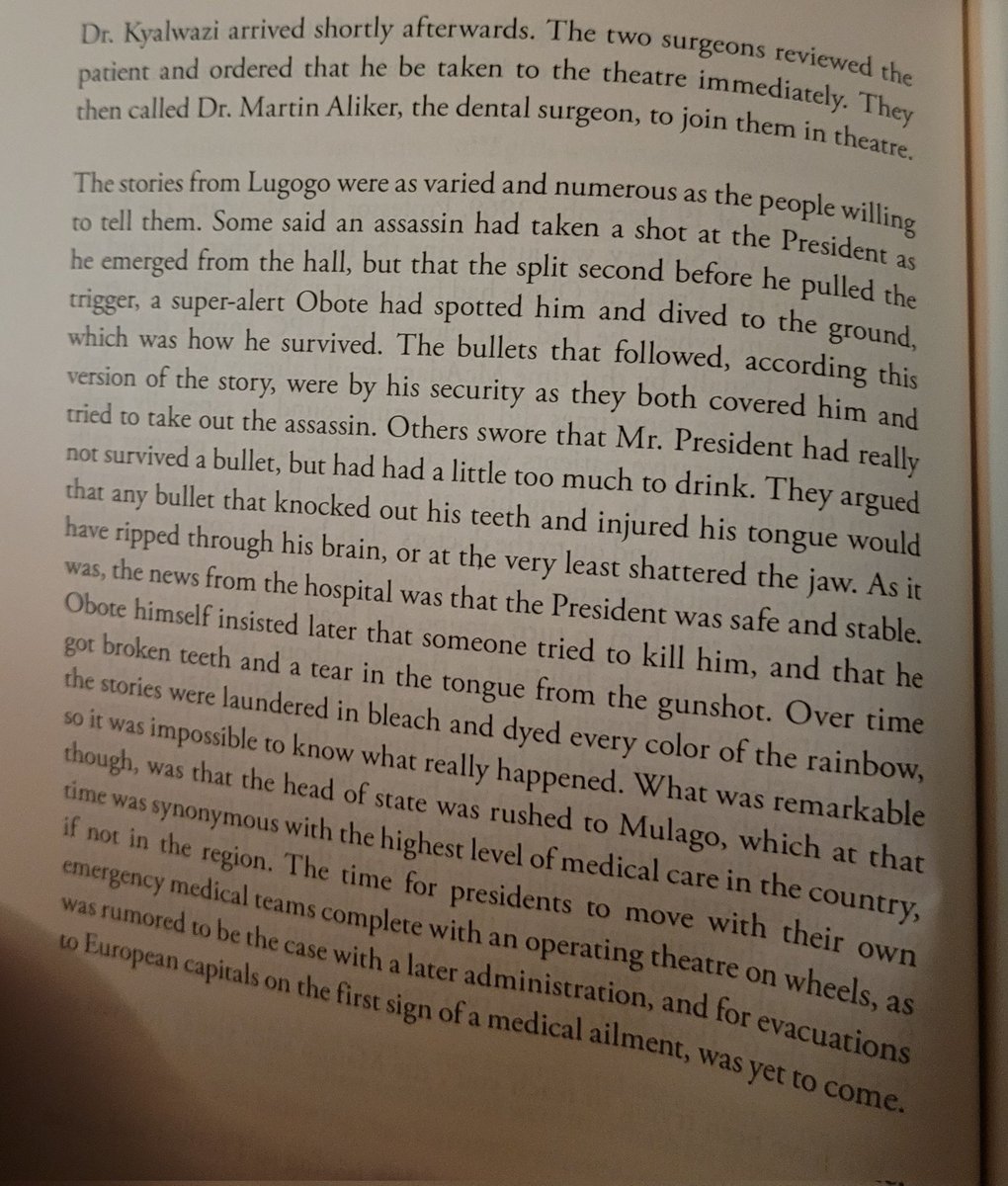

This is confirmed in the archaeological record. For example in the levant, the Natufian culture became sedentary and started storing locally abundant wild grains, even though there is no evidence of agriculture for a few thousand years longer.

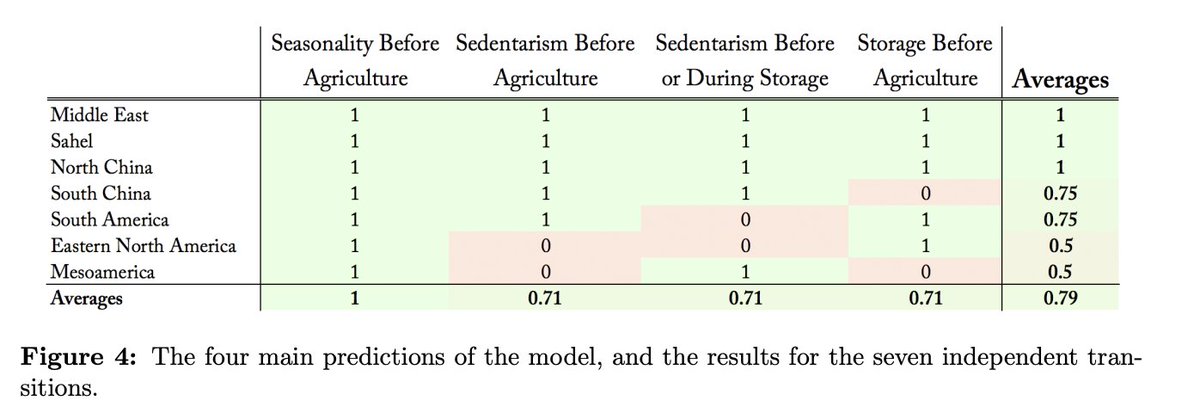

And this pattern is actually more general, if you look at all seven locations that invented agriculture, all of them experience a marked increase in seasonality leading up to invention, and all of them had at least another "hit" for the theory.

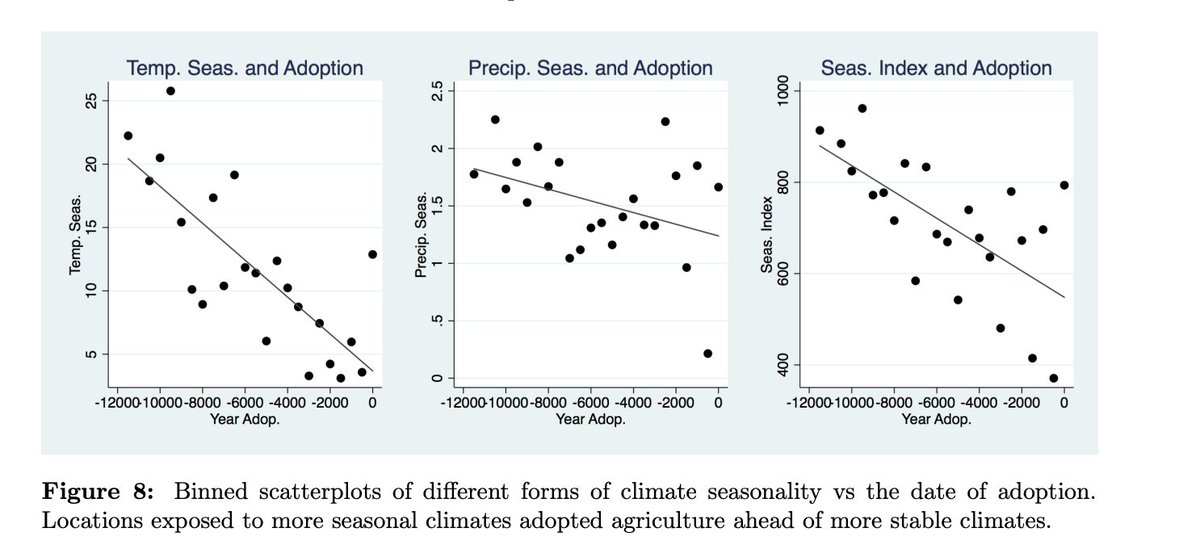

And now let's examine this systematically. I am using reconstructed climate data from Feng He at (UWisc). First of all temperature seasonality is just an astounding predictor of when agriculture arrives in a given location. Precipitation Seasonality slightly less so.

The regressions show the same thing. One extra degree of temperature seasonality is associated with starting to farm about 150-200 years earlier, with a bunch of controls. The effect weakens but can still be picked up even when looking at individual 15x15 degree squares.

Now let's look ONLY at Invention. Can we predict the seven location and times? Yes. The coefficient on temperature seasonality is both economically and statistically significant, while precipitation has the right sign but is imprecisely measured (only three subtropic inventions).

Look at that last column, the one with added controls for PRESENT DAY seasonality. The coefficient for contemporaneous temperature seasonality still works, while present seasonality does not. This excludes a bunch of correlations with present day income/archaeological budget.

And now let's look only at the SPREAD of agriculture, by measuring the probability that a non-farming neighbor will start farming, after one of their neighbors has already started farming. Not only did seasonality make agriculture easier to invent, but it also hastened its spread

We can examine this in more geographic detail in the West Eurasian context, by looking at the spread of farming from the middle east into Western Europe.I get basically the same results even when controlling for year on year volatility (the Ashraf & Michalopoulos variables)

So as predicted by my theory, higher seasonality (especially temperature), is a great predictor of date of adoption, probability of invention, and enthusiasm for adoption from neighbors.

But wait,...

But wait,...

It could be that high seasonality is indeed an important key to the puzzle, but not because of my favored storage explanation. Maybe seasonality -> large seeded grasses, and this feeds into the Blumler story (popularized and expanded on by Diamond)?

To show that storage has independent explanatory power, I next focus only on the portion of the sample that had access to wild cereals (the Middle East). All of these locations had very similar access to domesticable species (and less variation in climate than the full sample).

Here climate is similar enough, and locations close enough together, that seasonality no longer predicts adoption. But still we can see the imprint of the need for storage in the data.

The point of nomadism is to access diversified food sources. The more variation in altitude, the more variations in microclimate are likely to be large, and the more diversified the resources available to the population.

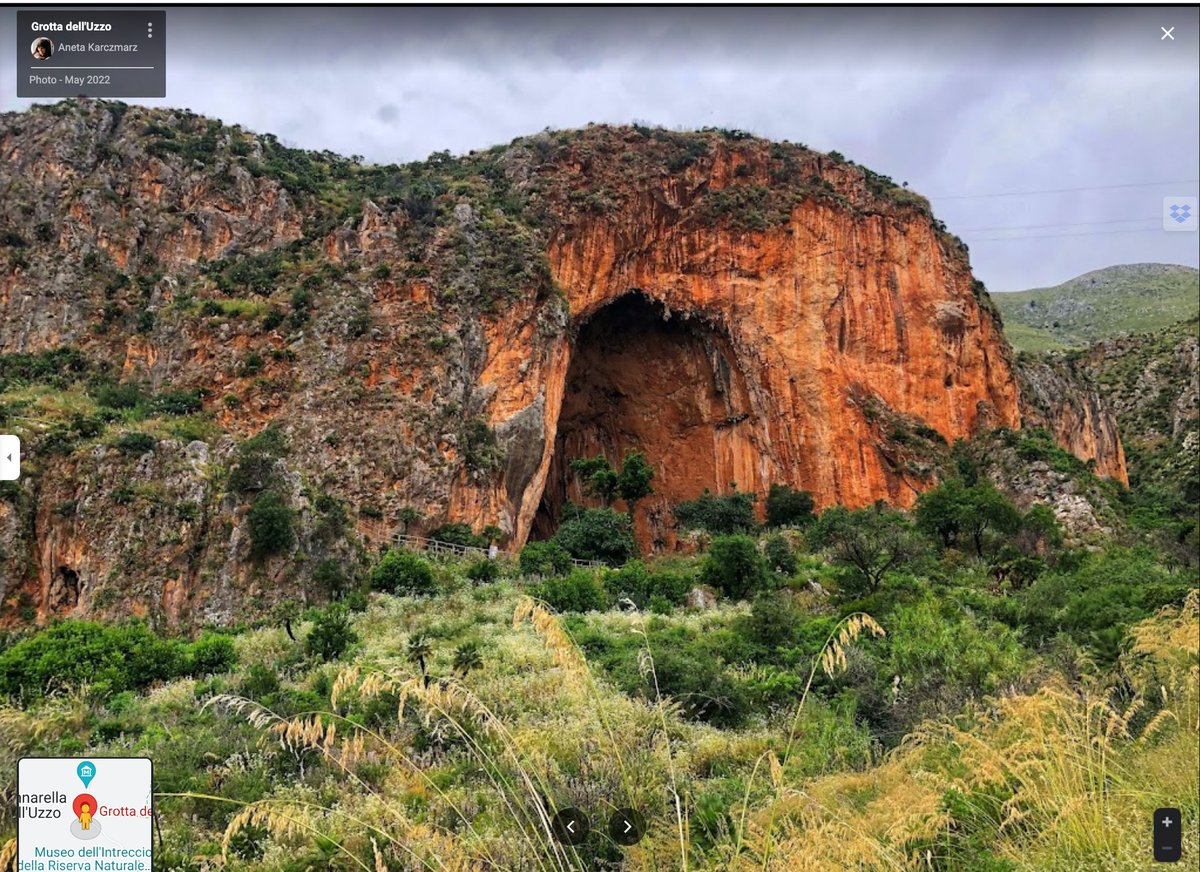

E.g. Grotta dell'Uzzo, the earliest Neolithic site in Sicily. Note that it's on a slope next to the coast. You have maritime resources, a small coastal plain, the slope itself, and the reverse slope on the other side. Would be a great place to become sedentary farming or not!

(For this insight I am grateful to the late Sebastiano Tusa, one of the great Sicilian archaeologists, who sadly perished in the crash of Ethiopian Airlines 302, due to Boeing's callous disregard for established aviation safety engineering principles)

Note that whether variations in altitude favor or delay sedentarism depends on the scale of these variation. If all the variation is within say 5km, you can be sedentary and still access it. If it's over 50 km, you need to be nomadic. If it's 200km away, it's far even for nomads.

These are the sites we are working with. Look at those four sites, and some representative terrain crossections in Fig 12, local variation increases vertically, and distant variation increases towards the right.

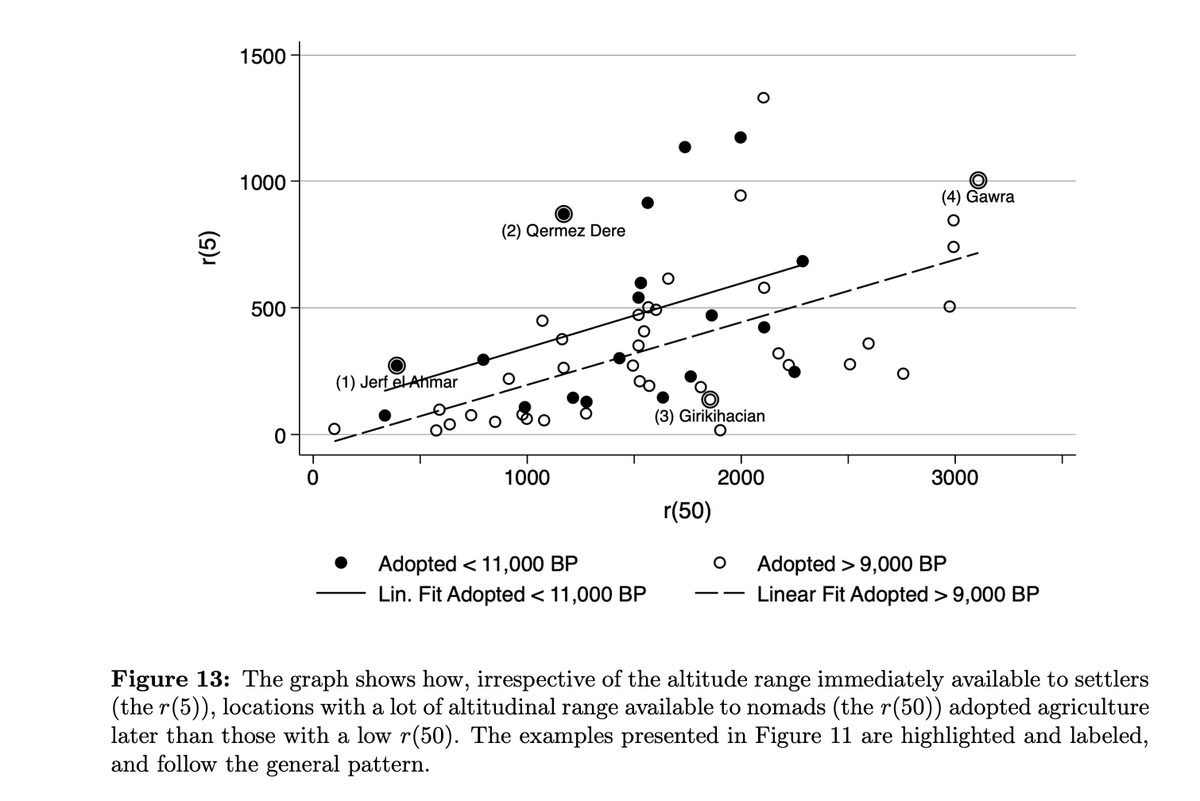

And here are the sites plotted r(5) is the range of altitude within 5km (available to settlers), while r(50) is range of altitude within 50km (nomads only). The graph compares the first third of sites to start agriculture, to the last third.

Note how all those places with super high r(50) adopted late? That's because nomads wouldn't want to become sedentary to avoid losing access to uncorrelated food sources. At some point farming became so advanced they made the switch anyway, but they held out!

Also note how for any r(5) you pick, the black dots (early adopters, tend to have less r(50) than late adopters. Regardless of what the very local environment looks like, if nomadism is still effective risk mitigation strategy, people didn't start farming.

Regressions confirm! The higher the r(50), the later the adoption date, by about 500yrs per 1000m hill. This is true even controlling for variation close by (which could be the Tusa Effect: great place to be sedentary), and r(200) which is too far even for Nomads.

Ok, last bit of evidence I promise. Remember how people got shorter when they started to farm? Well in the cases where we can distinguish the, they got shorter WHEN THEY BECAME SEDENTARY.

Usually we see the two together, but in the cases where we can distinguish, the drop in height seems to start in the Mesolithic (sedentarism) not Neolithic (agriculture).

And this makes sense, because when you become sedentary you smooth out food availability but lose access...

And this makes sense, because when you become sedentary you smooth out food availability but lose access...

...to some food sources that are now too distant to exploit. You are trading lower means in exchange for lower variance, but height is mainly determined by average food consumption, not discontinuities.

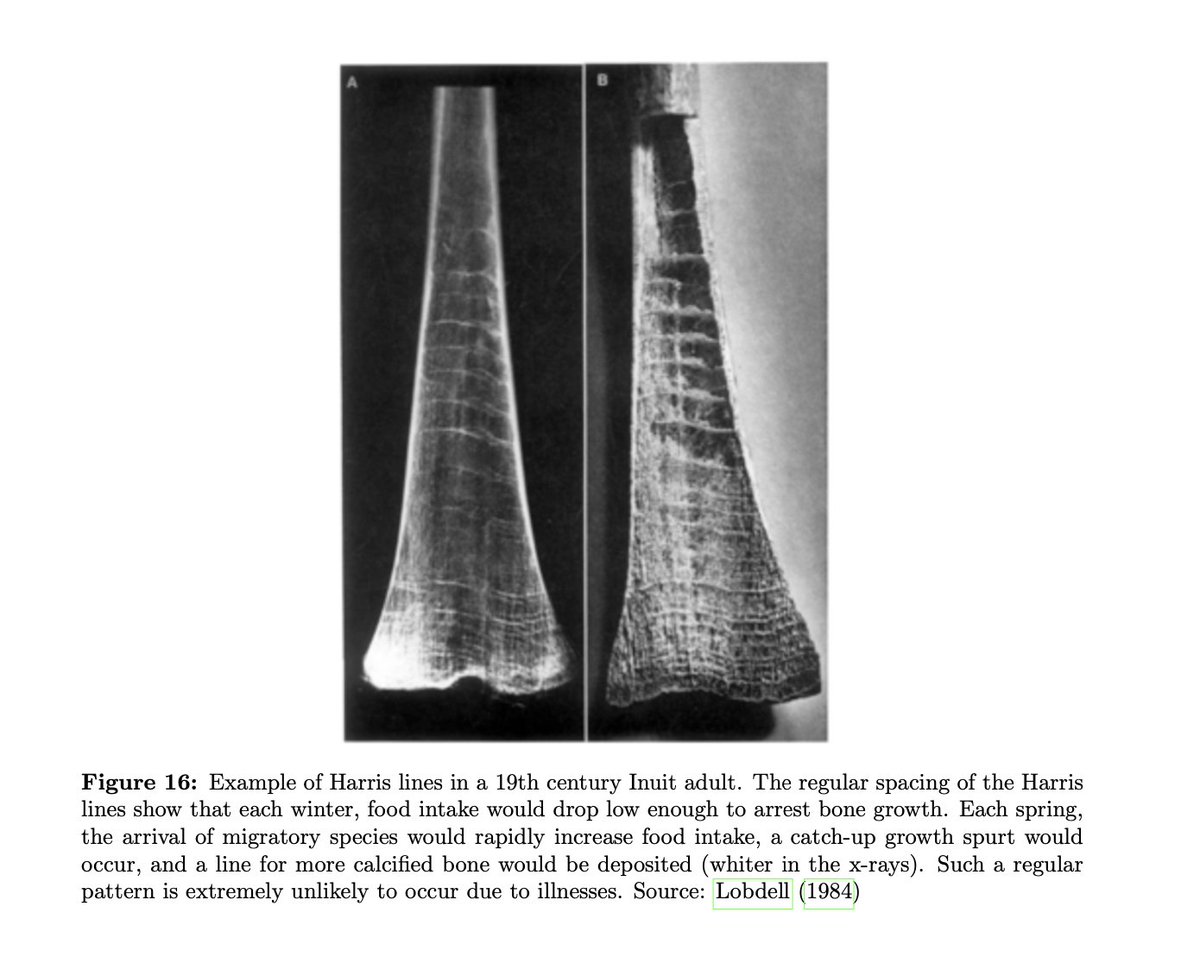

In fact if we look at something that does record sharp decreases in food availability, like Harris Lines, we find that Nomads were indeed taller (higher mean), but had many more Harris Lines (subject to more famines).

So here we go:

1), 2) and 3) are explained by the appearance of highly seasonal conditions,

4) is due to people losing access to dispersed food resources,

5) is people becoming sedentary in order to store.

Every other theory can explain what happened in specific places (6)

1), 2) and 3) are explained by the appearance of highly seasonal conditions,

4) is due to people losing access to dispersed food resources,

5) is people becoming sedentary in order to store.

Every other theory can explain what happened in specific places (6)

How close do you think I got?

And now, for the news. I am on the market for a EU job. We are just too far away from family, and due to age our parents are uninsurable to come to the US.

I have twins that are about to turn three and have yet to meet my parents. This is unacceptable. So we didn't apply to renew our visa, and will be returning to Europe one way or another this summer. Alea iacta est.

The second R&R of this paper is under revision at the QJE, I have a coauthored PNAS, and two handbook chapters with Luigi Pascali and Paola Giuliano, as well as some cool near-working papers on Russian Serfdom and Mafia and Labor Unions.

Our main concern is a EU location (we are done with visas) with a local labor market that will support gainful employment for somebody that speaks six languages and is super organized/practical, but has been out of the labor force for parenting for a few years.

As for my job, I have found the variation in academic jobs is considerable but is far less than the options for spouses, and I get along with people easily and don't need a particle accelerator to do my work, so I would be happy with a wide variety of jobs at EU institutions.

Ok kids are up, back in a few hours.

Sorry just a correction. We are looking in the EU+ Switzerland

Here's the latest version of the paper: andreamatranga.net/uploads/1/5/0/…

A couple of takeaways from the project:

1) When seasonality increased, a bunch of human populations, far removed from each other genetically and culturally, were "given the same test". And they came up with remarkably similar answers.

1) When seasonality increased, a bunch of human populations, far removed from each other genetically and culturally, were "given the same test". And they came up with remarkably similar answers.

This puts another hole in the already sinking hull of "differences in modern day development are driven by genetics".

2) If humans became settlers because of a desire to store food, it tells us something about our innate evolved risk preferences. Eating a little all the time is better than eating a lot some of the time and sometimes starving.

The closer you are to the subsistence limit, the more you care about occasional shortfalls. Even after killing a Mastodon, nomadic HGs didn't know if they would be starving next month.

The reason why I think this wasn't all figured out sixty years ago is because storage has been EXTREMELY successful at smoothing seasonal consumption in farming communities. Thanks to granaries (and money) if you are in abundance today, you will not be hungry in the near future.

Settlers don't worry about week to week or month to month famines, they worry about at least annual issues like crop failures, or losing your job.

This also has development implications! It suggests that trying to get poor farmers to improve the best outcome (e.g. fertilizer) is unlikely to be as effective as things that get rid of the worst outcomes.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh