When we talk about science and its impact on policy and decision-making during the pandemic, it is quite common to suggest that difficulties are simply a function of scientific uncertainty. That is, if we had perfect information, we would make optimal decisions.

However, Roger Pielke in his book The Honest Broker (cambridge.org/core/books/hon…) points out that scientific certainty or uncertainty is only part of the equation. The other key element of science-based decision making is values consensus.

Decision making during the pandemic may have multiple objectives, some of them competing or even contradictory. And there may be values that can be embraced publicly, and those that cannot.

It's easy to say "I think kids are important" publicly. What kind of monster is anti-kid? (Now, now, it's a rhetorical question, no names please). But it may be harder to publicly say "I mostly care that my business remains productive, even if that comes at a cost of deaths"

So we have this disconnect between publicly asserted values consensus ("for the kids", "all in this together"), and lack of consensus in our non-public worlds.

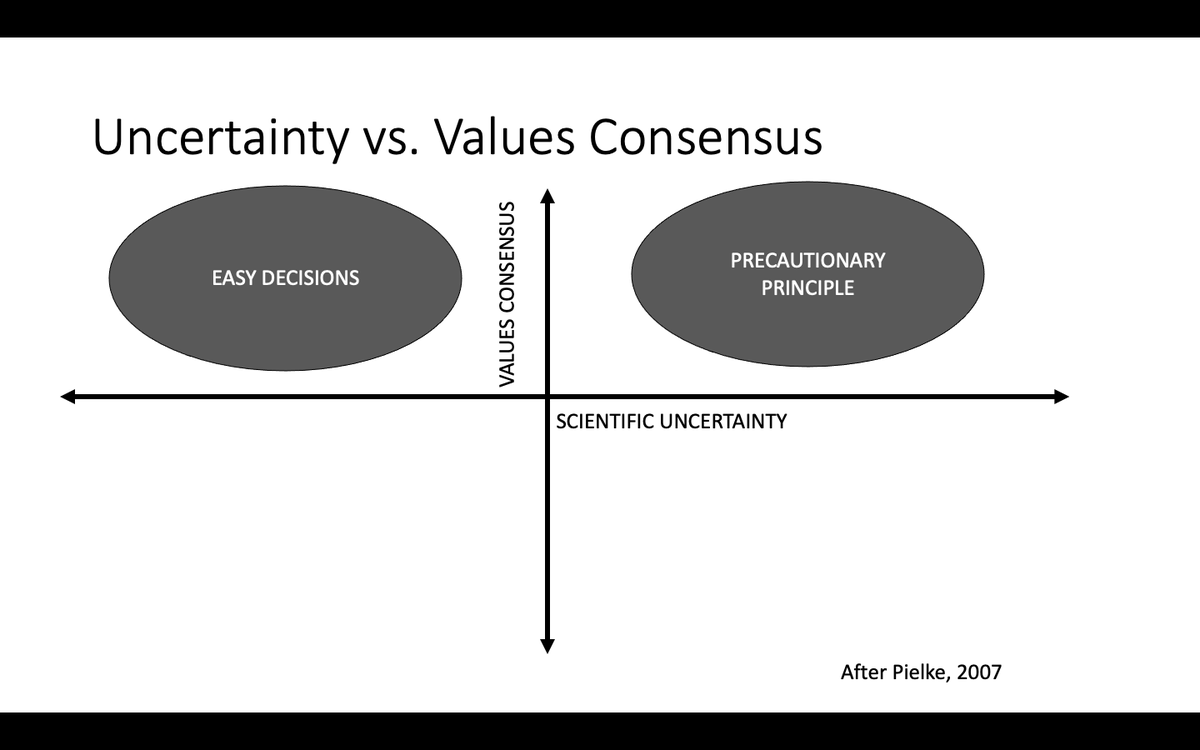

Using Pielke's 2-dimensional framework rather than a unidimensional framework that only references scientific uncertainty, is enlightening. As he tells us, decisions are straightforward when we have low scientific uncertainty, and we have values consensus.

In fact, with Pilke's framework, uncertainty probably becomes LESS determinative of action than values consensus. If we agree on what we need to achieve or prevent, we'll act according to the Precautionary Principle even if we have substantial uncertainty.

The hardest decisions (as Pielke says, and I think he's right) occur when we don't have values consensus, and we have scientific uncertainty.

But I think that the situation we found ourselves in with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, early on, (as demonstrated by China's elimination of SARS-2, though not before it went global) was that we had low uncertainty on how to control the disease, but no values consensus

At least behind closed doors. I think if we had really believed the rhetoric we were spouting publicly ("all in this together"), with the degree of scientific uncertainty present, we'd have eliminated SARS-CoV-2, or controlled it far better.

But I don't think the public rhetoric reflected true values of influential interests, including governments, though they couldn't say that out loud.

As Pielke says: “Uncertainty is also a resource for various interests in the process of bargaining, negotiation, and compromise…"

And I think this is why we've had so much MANUFACTURED uncertainty during the pandemic.

And I think this is why we've had so much MANUFACTURED uncertainty during the pandemic.

If the course of action is clear based on low uncertainty around an intervention like masks, (there really is no meaningful uncertainty around what masks do. We literally f-ing made influenza go extinct for two seasons, for Pete's sake), and we're sincere in our rhetoric...

..."we care about kids", then these are easy decisions. That's why you have to manufacture uncertainty. You take no-brainer decisions, and open them up for debate.

I think manufactured uncertainty has come in different forms during the pandemic. The most obvious is the very slick, well-funded disinformation ops that we've all been subjected to, as documented by @karamballes @AliNeitzelMD @CDPNetworkMap and others.

But academic medicine has also been embarrassingly present as a source of manufactured uncertainty. Using the rhetoric and tools of evidence based medicine to mix high quality studies with garbage studies, because you don't want to have to take the action...

...implied by the results of high quality studies, is an example of manufacturing uncertainty where none exists. (Note: RCT of n95 respirators where you put on a respirator once you come within some arbitrary distance of a person with whom you share air is analogous...

...to doing an RCT of umbrellas in thunderstorms, where you walk around in the storm for a while before opening your umbrella. Yes, if you use an umbrella like that, you still get wet).

But the most shameful example of manufactured uncertainty has come from public health authorities themselves. In Canada that has taken the form of hiding public data, ceasing to report some kinds of outbreaks altogether (as Ontario did with school outbreaks in January 2022)

and limiting the accessibility of testing, so that the pandemic can't be measured or understood. That serves no purpose other than manufacturing uncertainty so that you can take policy actions that would have been untenable had relevant information been in full view of the public

Anyway, my thinking on this continues to evolve. I hope others find this to be a useful framework.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh